Tapestry of Scotland: The people’s creation

Move over Bayeux Tapestry, there’s a new contender for the world’s most talked about piece of embroidery. The Great Tapestry of Scotland is 70 metres longer and takes as its vaulting subject matter the story of the nation from pre-history to the present day. That’s 400 million plus years, while the French design focuses on 1066. Well, when you’ve an army of volunteer stitchers at your disposal, why not go large?

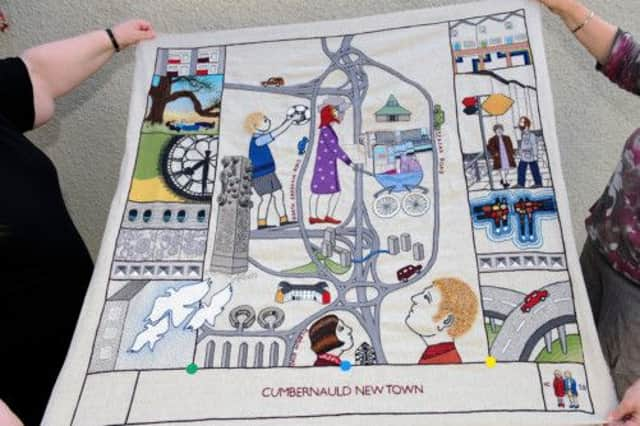

And large is what the tapestry is, comprising a timeline of 160 panels depicting key moments of Scottish history, and the personalities who made it happen. It will stretch 143 metres across the Main Hall of the Scottish Parliament when it is displayed for a month from Tuesday. The brainchild of Scottish writer Alexander McCall Smith, inset right, artist Andrew Crummy and historical writer Alistair Moffat, the project has taken almost 1,000 stitchers thousands of hours – up to 800 hours for each 100cm by 50cm panel. It has used 30 miles of woollen yarn and is the longest embroidered tapestry in the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKicking off with the splintering ice dome over Ben Lomond, the tapestry romps along covering everything from the fall of Dumbarton Rock to the Vikings to the reconvening of the Scottish Parliament and the invention of the Hillman Imp. People depicted in what Moffat calls “freeze frames of history” range from Billy Connolly and Andy Murray to Robert Louis Stevenson and Maw Broon. There’s also an accompanying album of 40 tracks by Greentrax Recordings including classics such as The Jeely Piece Song and Sheena Wellington’s A Man’s a Man For a’ That.

Teams of volunteers were sent Crummy’s sketched panels, a palette of wools and a deadline and set to work. Along with the great and good, battles and inventions, they’ve stitched the stories of nameless generations of ordinary Scots and, as is the way of these things, embroidered a little of their own lives into their work as they ate, lived and slept the tapestry. Thus there’s an anachronistic pinkie nail-sized iPad, a kilt in a battle scene for a clan that was actually home that day (but it’s the stitcher’s father’s tartan, so fair do’s) and no doubt other tiny moments of personal history that have crept in. We’re not saying where. You’ll have to go and look for yourself.

“Not only has the team of artist and stitchers created a stunning record of Scotland’s history, but the project has brought together hundreds of people in all parts of Scotland in joint artistic endeavour,” says McCall Smith.

“I salute the visionary artist, Andrew Crummy, and his team of hundreds, led by Dorie Wilkie. I salute their magnificent artistry. I salute their generosity. I salute their good humour. This tapestry is their creation, given to the people of Scotland and to those who will come to Scotland to see it.”

The Bayeux Tapestry still speaks to us over nine centuries on. If the Great Tapestry of Scotland has a similar legacy, what will our descendants make of us?

As Moffat says, “Most important have been our efforts to make a tapestry that distils Scotland’s unique sense of herself, to tell a story only of this place, and without bombast, pomp or ceremony, to ask the heart-swelling rhetorical question; Wha’s like us?”

The Great Tapestry of Scotland, Main Hall, Scottish Parliament, Tuesday-21 September, free; The Music and Song of the Great Tapestry of Scotland, Greentrax, double album, £15, www.greentrax.com

WINTER SPORTS

Susan Finlayson from Loanhead, worked on the Winter Sports panel with Linda Jobson when she wasn’t singing with her Sing in the City group.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I first got involved with the Great Tapestry of Scotland after my mum volunteered me. I spent several months helping to trace Andrew Crummy’s designs on to linen, and making up the kits to send out to the groups, then visiting them to help. I had never done embroidery of this sort and never imagined I might be part of it as well. However Dorie Wilkie had other ideas and presented me with a panel and the name of a lady who would work on it with me – to say I was dumbfounnert would be an understatement.

“Linda Jobson and I had a lot of fun working together and will stay in touch. I stitched the three shinty players and modelled one on my husband, one on my dad and one on my uncle and copied their tartans for the players’ kilts. For people already interested in history, the tapestry provides a different perspective on events and people. For others, the pictures tell a story without burdening the viewer with too much information and, in a lot of cases, can inspire you to find out more about a person, event or subject. Several times while tracing panels we stopped and Googled to find out more; I have probably learnt more about Scottish history through the tapestry than I ever did at school.”

BORDER REIVERS

Veronica Ross and the Smailholm Stitchers worked on the Border Reivers panels.

“Our panel is a powerful one and demonstrates very nicely what the reivers were about. It arrived with Andrew Crummy’s drawings of the men in helmets and horses with windswept manes, and the rescue of reiver Kinmont Willie from jail in Carlisle Castle on 13 April, 1596 by Scott of Buccleuch and his men.

“We added the moon, to represent Neil Armstrong, who was descended from a reiving family. Most of our group of 12 live in the village of Smailholm and we started off thinking it was a bit of sewing, but it involved forays into history, literature and music. We had lived in the shadow of the tower for years but thinking about it made us understand how the landscape facilitated the reivers’ activities over 300 years and why Borderers are such an independent breed.

“The nice thing is it’s not just snapshots of battles and events, it’s got a huge amount of social history of people and developments like the Enlightenment, or more nebulous things like pop culture, Scottish cinema, and movements in time, rather than past key events and it features ordinary people like fisherwomen and washerwomen.

“It’s about people and is a work of the people. To be part of producing a major piece of public art that people will look at is amazing.”

PYTHEAS CIRCUMNAVIGATES SCOTLAND

Margaret Macleod and Mary Macleod (no relation), the Isle of Lewis Stitchers, worked on the Pytheas panel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I come from very near the Callanish Stones so I know them well and liked that it was local to me. The panel also had significance for me and my friend Mary who helped me, because our husbands were merchant navy officers. We put some Gaelic in a corner too. The panel is early in the timeline, 340BC, and something I knew little about. It beggars belief they came all that way in such a small boat. It’s also a reminder of how old the stones are – no-one knows for definite but they’re around 2900 to 2600 BC.

“I don’t normally do this kind of work – I’m from a family of Harris Tweed weavers – but I loved every bit of it. I did most of the work myself, with Mary’s help. This meant I got a say, in the interpretation of the sea for example – you think it can’t possibly be those colours, but it is – and the stones in the moonlight was me. It took over six months of my life, the dog’s life, my husband’s life. I worked at the Hub too, so have seen a lot of the panels and Andrew Crummy’s drawings are brilliant. When you see the whole thing together, 400 million years of history, it will be astounding.”

THE SCOTSMAN

Jan Young and her Penicuik Panelbeaters, worked on a panel celebrating the launch of The Scotsman newspaper in 1817.

“I’ve embroidered all my life and it sounded very exciting so I volunteered to work at the headquarters where it was being co-ordinated. I mentioned I used to work at The Scotsman before I became a business consultant and when I got a panel to work on with the others, that’s what it was. There’s a pigeon for the way the football results used to arrive, and a David Hume quote in shorthand from editor Ian Stewart: ‘It is seldom that liberty of any kind is lost all at once’.

“The Penicuik connection is there in the paper mill, Scotland’s biggest, which supplied the newsprint for The Scotsman. For a tiny country we have played a big part on the world stage, whether it’s philosophy, the Bard, the diaspora, and to have it depicted in a beautiful work of art, it really is special.

“Everyone cared deeply about it and put their heart and soul into it. It’s been absolutely wonderful to have had the opportunity to have a tiny input into it. I have loved it.”

SCOTTISH RUGBY

Margaret Ferguson from Edinburgh and the Mascots group worked on a panel celebrating the first international rugby match, between England and Scotland in 1871, which Scotland won.

“I put my name down to do this and the rugby boys turned out to be fascinating. I didn’t know any of the others before, but we got together every week. Then we started wanting to turn it round and do an upside down stitch so it was like tugging the blanket. That’s when we started taking it away and doing a bit each.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Our panel was one of the later ones and it wasn’t all sketched on when we got it so we did some research and had input and Andrew then sketched it in. It made it more unique and involving, that we did some of the research. I enjoyed that. That’s what community work is all about. It’s not somebody deciding every last stitch, colour and design. It’s everybody having an input.”

THE HILLMAN IMP

Lesley Thornton and her Tillicoultry Needles and Gins group worked on a panel celebrating Ravenscraig and the Hillman Imp.

“Our craft group meets in the Woolpack pub in Tillicoultry, hence the name, but we all took it home to protect it from spillages. We were nervous at first, but we’re expert stitchers now. About seven of us worked on it for eight months and it took over our lives. Dozens of hours went into it – each of the Hillman Imps took six hours alone.

“The figures are Elizabeth Yuill and Bill Simpson from Young in Heart, a film about Hillman Imps. Everyone had a memory of a Hillman Imp, either their first car, or their parents’, and someone’s dad worked at Ravenscraig. Everyone had links.

It makes you realise how much talent there is hidden away in people’s houses, in small groups, all over the country. It’ll be a national heirloom and give a sense of Scottish history, not necessarily the obvious historic facts, but things like the Hillman Imp, domestic appliances made out of Ravenscraig steel (we deliberately put the iron next to the man), things that meant a lot. It’s nice to see history done in a historic craft rather than something grand, and Scotland has such a strong textile heritage.”