The privilege and pressures of swapping a city medical practice for one on an island

Failing to be me

After graduating and training as a GP, slowing moving from the east to the west of Scotland as I did so, I met my wife, who was an anaesthetist, and we set up home in the suburbs of Glasgow. We should have been happy, and to an extent we were, but I was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with myself and the job I was doing.

Writing this memoir, I re-examined those times and began to understand what had happened to me, how I had lost the vision I had as a child. I wasn’t a village GP, I was a city one. My kids didn’t have woods and burns to play in, they had a large garden at the bottom of which was a lane where teenagers sniffed glue.

Changing places

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEventually, my wife and I both knew I was in the wrong place, we needed to search for a different medical practice. My wife was from Bute and used to island life, I hated it and was very unsettled when we visited, feeling stranded when the last ferry had tied up for the night. So naturally, I applied for a job on remote Eday one of the islands of Orkney.

As I wrote, I became even more aware of the support my wife had given me then. She had swapped an anaesthetic career for part-time general practice and was balancing work and motherhood at the same time. She could see more clearly than I could what was happening and was definitely the stronger one at this time. When the phone call came through from Orkney Health Board, offering me the job, she was the one who was confident we were doing the right thing.

Back in time

The move to Eday was a move back in time, a relaxation from the pace of urban life into a reality that I recognised almost immediately. Describing those first few weeks on the island, I realised I was unwrapping my childhood of open fires, Tilley lamps, heather hillsides, and farming. One croft I visited had no running water, and no electricity. Fish were hung out to dry on wooden racks before being salted and put away for later consumption. The old lady I was to examine lay in the box bed she had been born in nearly 80 years earlier.

Each house I visited or patient I saw forced me to re-think the attitude I had adopted to medical care. I had been distancing myself from the person I was to treat and focusing only on the disease puzzle to be solved. On Eday I couldn’t do that anymore.

Community living

Small island populations only survive if they are communities, if a sense of responsibility to others is lost then they slowly degrade. As I wrote, I wanted to capture the interwoven nature of the community at the time, how we relied on each other, perhaps without ever really thinking about it. Whether we were looking after a sick seal pup with distemper or searching for a person missing from his home. There was no thought that we wouldn’t play our part, however small.

At a time when there were no mobile phones, communication between people relied heavily on word of mouth and landline telephones. The speed with which information was transmitted still amazes me. Confidentiality was a very different concept to what we have now. Respect would be a better word for how details of life were dealt with.

The fear of failure

Working on a remote island is very different from urban practice. For the first two or three hours of any major event, you are the only medical response. You may be completely alone, either as a nurse or doctor, for some islands had exclusively nurse-led care. I felt readers should experience something of what that total responsibility feels like.

Ultimately, as I put the thoughts down on paper, I came to realise that the underlying emotion was the fear of failure. In some ways, it’s the anxiety of not coping that drives our learning and makes us want to acquire new skills. Whether we’re working in conflicts zones, like David Nott describes in his memoir War Doctor, or carrying the total responsibility for care for an island population, deep inside each doctor and nurse, there is an often unrecognised fear. Eday taught me to put that fear into perspective.

All creatures great and small

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a doctor on the island, there was an assumption that I would try to treat all living creatures. Remote as we were from emergency veterinary care, there were times when I felt more like James Herriot than a GP. Most folks were content to look after farm animals themselves, it was the wild ones that made them call me. Especially if it was a sick swan that was blocking the airstrip, preventing possible air ambulance landings. That was definitely my responsibility.

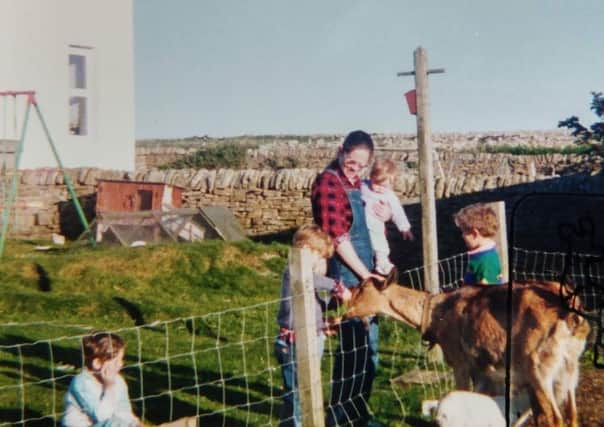

I ended up using a small shed beside the garage as a mini animal A/E department. We looked after a sick swan, a seal, mallard ducklings left behind by their mother, a goose, and the odd goat. I loved caring for them.

Landscape

As we settled in the island landscape, I became more aware of its physical presence, of its moods if you like, its changing temperament. Using prose to encapsulate this didn’t seem to do Eday justice, and so the poems that pace the stories in the memoir emerged. Initially, they were a way for me to create the background I needed for my stories, gradually I came to understand that they were something deeper.

A moment in time

I wanted to write a memoir that captured a unique moment in time. Writing the island stories down they appear as if they may have come from the 50s and not the 80s. It was a time of transition, I now realise, as old crofting practices, methods of self-reliance, changed. When we went to Eday there was one supply boat a week in the winter time; in a very short time, the daily ro-ro sailings started. There was an unreliable landline connection to mainland Orkney; in very few years this became a microwave telephone link. In fact, it wasn’t that many years previously that a mains electricity supply had been established, the old generator shed for the surgery was still standing in our paddock. I learned about myself, and about how to approach life, from the folks we lived with all those years ago. I had to be honest with myself to see how I had missed the mark I set when I was a boy. It was the combination of islanders and their island that put that right for me. No matter what task I undertook as a senior doctor in the health service, I knew I could always test whether the ideas we had were robust by asking – how would that work on Eday?

Close to Where the Heart Gives Out: A Year in the Life of an Orkney Doctor by Malcolm Alexander is published by Michael O’Mara Books tomorrow at £16.99