Graphic novel Altitude a bittersweet celebration of youthful limit-testing

Sports like skiing and climbing, by contrast, offer a progression: you feel safe skiing a 40-degree slope? OK, how about 45 degrees? How about 45 degrees and narrow? How about 50 degrees and narrow with a cornice to negotiate at the top? When it comes to extreme sports, everyone has a limit – a personal risk/reward threshold – and part of the appeal for many people is finding out just how far their skills and their nerves will take them.

There are some very notable exceptions, but in most cases this desire to test limits burns most fiercely in the young. Partly this is down to peer pressure. In a recent feature in The Surfer’s Path, legendary big wave surfer Jeff Hackman described what it was like growing up in Hawaii in the 1960s: “If you were around the [surf] scene then and you didn’t go [take off on a wave]... that wasn’t even a thought. If you were out, you had to go. It’d be humiliating if you didn’t.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEvery surfer knows the feeling: a solid wave rears up and you’re in position for it; everyone else in the line-up is wondering if you’re going to try and ride it or head for the safety of the shoulder. Older surfers, who have perhaps explored their limits a decade or two before and come to peace with them, might be more comfortable letting the unmakeable ones go; surfers in their late teens and early 20s, though, tend to be the ones throwing themselves over the ledge. The same is true when there’s nobody watching, too – often the young want to find out where their limits are whether they have an audience or not.

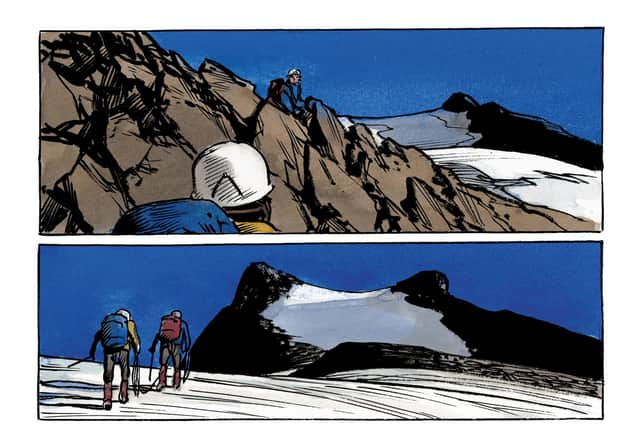

These years of self-discovery can be a dangerous time but they can also be a glorious time, and they are captured with uncommon honesty and beauty in Altitude (Self Made Hero, £16.99), a new graphic novel by the French artist and climber Jean-Marc Rochette, co-written by Olivier Bocquet and translated seamlessly into English by Edward Gauvin.

Rochette is best-known as the co-creator of the graphic novel Snowpiercer, made into a film by Bong Joon-ho in 2013, starring Chris Evans, John Hurt, Jamie Bell and Tilda Swinton. However, in his younger days his passion was climbing, and Altitude charts his rise from clueless beginner to seasoned expert, until he reaches that crucial pivot-point where he is operating at the furthest extent of what his body and mind can handle.

Rochette draws himself as a serious, somewhat dour figure with a passion for art, but his companion for much of his climbing journey is Sempé – a chubby-cheeked prankster who never seems to be out of his climbing helmet. The pair make a good double-act, and as they get older they progress from bunking off school to climb anonymous cliff faces on the outskirts of Grenoble to taking on the peaks of the 12,000-foot plus peaks of the nearby Massif des Écrins.

After a string of adventures, followed by the deaths of other climbers they know, a time eventually comes when Sempé declares he’s done with climbing. As he puts it: “It was fun when we were starting out, but now... I don’t know. I want to keep having fun, you know? Not count up the dead.” It’s a bittersweet, surprisingly emotional moment – a moment where the pair effectively come to realise that their limits are no longer compatible. Rochette accepts that “Sempé was right – the mountains were dangerous,” but in the same breath he observes, “I just wasn’t ready to listen quite yet.”

To say too much more would be to spoil the book’s gripping final third. Suffice to say that, in the end, Rochette too discovers where his limits lie, and comes to peace with the fact that there are some mountains he will never climb. It’s a familiar story arc, perhaps, but rarely can it have been more eloquently expressed.

To order a copy of Altitude visit https://selfmadehero.com