Commercial property: public projects produce stunning results

A balance will need to be struck between fitting in with existing buildings or landscapes but at the same time adding to – or at least not detracting from – the reason why the public is visiting.

Add to all that concerns about costs, value for money and sustainability and you potentially have a complex brief.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs Andy Davey of conservation specialists, Simpson & Brown Architects, says: “Taking an existing building and adapting it for visitors I sometimes liken to performing surgery on an awkward old friend.”

His company has just been appointed to work on the creation of a National Marine Centre in North Berwick, a £3.5 million project which will see the much loved Seabird Centre building, which sits in a prominent position on the seafront, expanded to encompass a wider remit of showcasing all marine life.

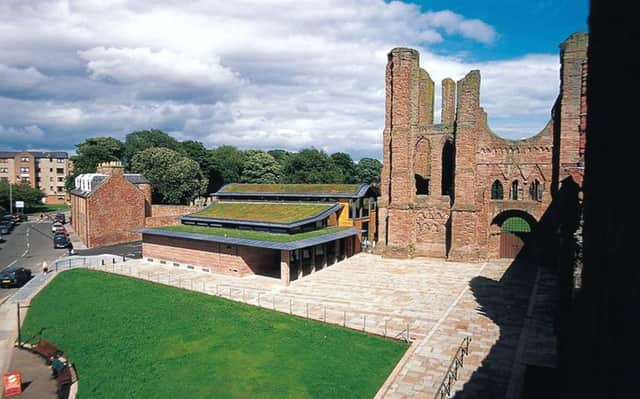

Davey worked on the original centre which was completed in 2000 and says the project sparked a specialisation which has seen the company work on, and win awards for, a range of high-profile visitor-related projects including the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, the gateway buildings at the Dawyck Botanic Garden near Peebles, the Arbroath Abbey Visitor Centre, York Art Gallery and, most recently, Rievaulx Abbey Visitor Centre and Museum in Yorkshire.

He says: “Our work focuses on respecting the past and responding to the challenges for the future, particularly with regards to environmentally sound, sustainable design.”

As yet, the North Berwick project is at a consulting and researching stage, and the architects hope to bring in the opinions of stakeholders to inform the finished building.

Grace Martin, project director for the National Marine Centre, says: “Andy and his team have a very strong association with the current building and a wealth of experience in visitor attractions, sustainability and sympathetic design.

“It will present the opportunity for the centre to achieve more of its charitable objectives by expanding and diversifying its education and conservation programmes, developing new activities and events, and enhancing the exhibition space.”

While the project gives Davey the opportunity to extend a building which was purpose-built as a visitor attraction, most of his projects are additions to buildings that are sometimes hundreds of years old.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAdding a modern building that suits the purposes of visitors, perhaps incorporating a cafe, shops and toilets, can mean that the new ideas are challenging.

Davey says: “If you are working with a cathedral for example and creating a new building in its environs you will get many different opinions of what is acceptable.

“Instead of copying the older style however, we aim for the newbuild to relate to what is there already, but enhance it and avoid being a pastiche.

“We liken it to the style of the visitor centre having a conversation with the existing building, but a polite, subtle one rather than a noisy one which can drown everything else out.”

Angel Morales-Aguilar, of LDN Architects, in Edinburgh, agrees. The company completed the innovative visitor centre at Abbotsford near Galashiels in the Scottish Borders, the Victorian home of Sir Walter Scott, in 2012.

He says: “Abbotsford is one of the most architecturally important buildings in Scotland so instead of trying to match the style, which would be nearly impossible, we created a building which we believe is a mirror of the original.

“Where Abbotsford is ornate and heavy with rich detail, the new visitor centre is simple, light and understated.

“The location is unobtrusive – you can’t see the visitor centre from the house, but you can see the house from the visitor centre.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe modern building was clad in untreated timber designed to age to become part of the landscape, while it serves as a gateway to the main house and provides all the practical things which visitors need, including parking.

The project also included major renovations on Abbotsford itself. The house has been open to the public since Sir Walter Scott’s death, but Morales-Aguilar says that the work aimed to improve access for visitors.

“The greatest room in the house is Scott’s study, but previously the route up to it was through the basement.

“We changed this to give modern visitors more of an authentic experience, they now make their way through the house to be presented to this fantastic, important room.”

Working with the Abbotsford Trust, and Historic Scotland, the team found solutions to make the house more accessible to all, with the addition of lifts for disabled access for instance.

Morales-Aguilar says: “With a historic house there are limitations on what you can do. While you would design a modern building to encourage the flow of people, here the trust’s volunteers are on hand as guides to make sure everyone has the best experience and for instance the smaller rooms don’t become too crowded.”

Davey says that throughout the design process, considerations such as the flow of people and the route through the building are paramount.

“But we also have to remember why people are here and designing a building to impart information – whether that is about the natural world or a historic site – is the prime motive of these buildings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Creating something that facilitates that is a challenge, but also an inspiring task.”

This article appears in the SPRING 2017 edition of Vision Scotland. An online version can be read here. Further information about Vision Scotland here.