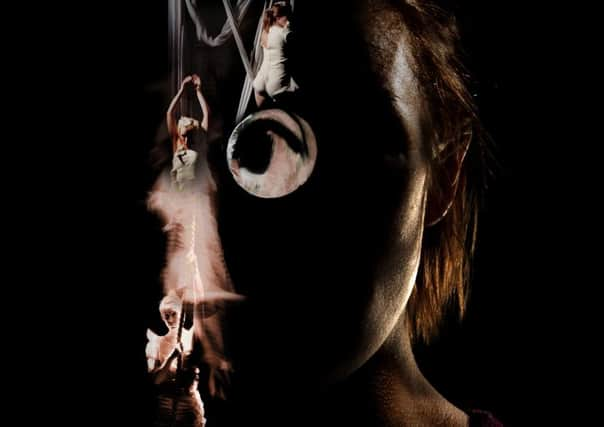

In Her Shadows, a dance show that wrestles with depression

Debbie Robbins had no intention of putting her life on stage for all to see. She just wanted to make a show that fused her passion for aerial dance with visual projections. But as the show began to take shape, Robbins realised the story beginning to emerge was, in fact, her own struggle with depression.

“It came out unconsciously,” she says. “And I was quite shocked that I’d done it to myself. But it was about getting it out of my body, a kind of healing through self-expression. It wasn’t a case of me wanting to say ‘hey everybody, here’s my story’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow Robbins’ experience will form a major part of this year’s Scottish Mental Health Arts and Film Festival (SMHAFF), as In Her Shadows tours to venues across the country.

The story starts when Robbins was 25, and returned home to Scotland after working as a fitness instructor in Australia. Difficulties with her family led to feelings of depression, and when talking to friends didn’t help, she looked elsewhere for support.

“I ended up going to see a counsellor,” she explains, “and I was so ashamed. I felt like a failure because going to counselling is such a taboo. But when I was there, it was totally amazing, it felt so empowering.

“I saw an art therapist who helped me visualise things – and that’s when I started my own company, A Blank Canvas. At the same time as going to counselling, I started learning aerial.”

It was at an aerial class that Robbins, a trained dancer, met puppeteer Rachael Macintyre. Together, they began devising a cross-artform show with the help of audio visual artist Robbie Thomson, and so In Her Shadows was born. The last piece in the puzzle came via the show’s director, Cora Bissett.

Known for her work on shows such as Glasgow Girls and Rites, Bissett introduced Robbins to ‘Today’, a powerful and frank poem by Jenny Lindsay. Inspired by the questions found on some mental heath forms, asking people to rank how bad they feel on a scale of one to ten, Lindsay’s poem describes her own very personal experience of depression. Yet there are aspects of her struggle that most people will recognise from some point in their lives.

“Jenny came along to rehearsals and read the poem to us,” explains Robbins. “And she was so open about it, it made me think ‘OK, somebody else is putting their heart on the line here.’ It felt like the perfect way to end of the show, because it explains so much.”

Creating a semi-autobiographical work may not have been Robbins’ original plan, but now it’s out there, she’s keen to play a part in removing the stigma surrounding depression.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“During rehearsals I realised I wanted to tell a story about depression. It was something I felt really passionate about because it happened to me. But also the taboo of going to counselling – I’m passionate about changing that, too,” she says.

Another performer with a passion for bringing things out into the open is RM Hubbert, or “Hubby” as he’s known. Winner of the Scottish Album of the Year Award in 2013, the singer/songwriter often talks about his experience of depression, something he has struggled with since the age of 15.

But now, along with fellow songwriter Drew Wright (aka Wounded Knee), he’ll be telling other people’s stories, rather than his own. Easterhouse Conversations is the result of a six month residency at Platform in north east Glasgow, during which Hubby and Wright spoke to users of the venue and residents in the local area.

“It was a really amazing experience,” says Hubby, “just going out and meeting people, hearing about their lives and how they were connected to Easterhouse. It took a few visits for people to really open up, which was fine because for Drew and I it was about getting to know these people and us all being comfortable with each other.

“Pretty much everyone spoke in great detail about the sad things that had happened in their lives – but also the really amazing things. Then we went away and wrote some music based on their stories.”

Eight new songs resulted from the conversations, written using the exact words spoken to them by the participants. The songs, which Hubby describes as “mostly happy with a couple of sad wee bits”, will be performed as part of this year’s SMHAFF and hopefully encourage others to have their own conversations.

“I talk about my mental illness a lot during my shows,” says Hubby, “and the absolute core of starting to deal with these issues is talking about them honestly, and more importantly, listening.

“The whole reason that mental health gets stigmatised, and people find it difficult to deal with, is because we don’t talk about it and we have pre-conceived notions of what it means to have mental illness.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMichael Emans of Rapture Theatre Company hopes that talking will form a pivotal part of his company’s 22-date Scottish tour. After almost every performance of Arthur Miller’s The Last Yankee, a representative from the Scottish Association for Mental Health or the “See Me” campaign will host a post-show talk and Q&A.

Written in 1993, Miller’s play focuses on two women who are being treated in hospital for depression, while their husbands attempt to understand the condition and how they can help.

“I’d love people to go away after seeing the play with a much greater understanding of depression,” says Emans. “And that it enriches them as a person, so that the next time they encounter depression, they’re perhaps in a better place to understand and engage with it.”

It’s not the first time Rapture has tackled this subject matter, having staged Joe Penhall’s Blue/Orange, and approached their production of Hamlet from a mental health angle. One of Miller’s lesser known plays, The Last Yankee explores the reasons behind depression, and the pressures placed on people by the environment they live in.

“I think of all Miller’s later plays, it’s one of the best written – it stands out as a little gem of a piece,” says Emans. “And it raises the question as to whether mental health issues are to do with the person or to do with their reaction to society at large. Particularly in America, where there is still this focus on the pursuit of the so-called American dream and the pressure to achieve success.”

Alongside the two husbands and wives, Miller created a fifth character, who remains still in a hospital bed throughout the 75 minute play. For Emans, Miller makes an important point about the nature of depression.

“He’s very specific about that other character,” says Emans. “that they don’t move or speak at all, and that they’re left on stage at the end. So when the play finishes, one woman has tried to move on and get better, the other woman has moved back a bit – and this third patient is in stasis. And I think it’s saying people can get better, but some people don’t, it’s ongoing.”

The Scottish Mental Health Arts and Film Festival runs until 31 October, www.mhfestival.com