Art review: Andy Warhol and Eduardo Paolozzi '“ I want to be a machine, SNGMA, Edinburgh

Andy Warhol and Eduardo Paolozzi – I want to be a machine, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ****

There are unfamiliar early drawings by Warhol, for instance, with the smooth and practised lines of fashion plate design. Paolozzi’s early drawings, also well represented, are in contrast fierce and wild, building on the inspiration of Picasso and already using collage, the technique that defines him that he adopted from the Surrealists. He found in it a metaphor for the fragmented experience of the modern world. Warhol did something similar by constantly using the camera as the basis of his work, either translating a photographic image into a print or drawing, or just as it is, but either way stressing its detachment.

Advertisement

Hide AdThey did once exhibit together. It was in 1968 with three others in the Four Seasons Restaurant in New York. Both are also seen as originators of Pop Art, although Paolozzi always dismissed that suggestion with a characteristically derisive snort. He saw Pop Art as trivial. He may have been right. Nevertheless, Pop Art did evolve from an insight that, quite independently, he and Warhol shared: the old boundaries that separate Fine Art from all the other images we make are meaningless. In a kind of visual democracy, all our imagery is significant; art has to embrace that to be relevant.

For Paolozzi, however, the modern was still linked to the past. In several works here he makes the point by collaging diagrams of modern machinery onto images of classical sculpture. In Athena Lemnia von Phidias, for example, the cylinders and crank shaft of an engine are superimposed on a Greek Athena.

Warhol also saw that all images count, but, far more numerous and pervasive than ever before, that they are nevertheless ephemeral. They carry no historical baggage and circulate as casually as the coins in our pockets. It is their instantaneity and potentially endless repetition that are distinctive of modernity. Here ten versions of his classic Marilyn print hung in a block make the point. They are all in different colours yet basically identical and instantly recognisable. Indeed Warhol’s Marilyn has been so successful that it is now more familiar than her actual appearance. He has turned the ephemeral into the iconic, quite a trick. He does something similar with his black and white portrait of Jackie Kennedy in mourning, repeating the image twice, simulating the grainy texture of newsprint.

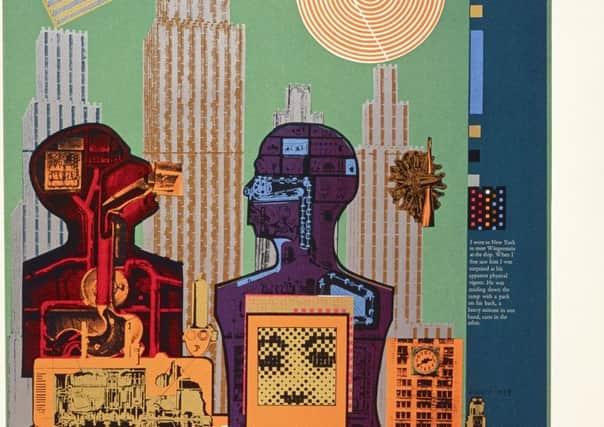

With its provocative subtitle, “I want to be a machine” – a remark made by Warhol – this exhibition also pushes the analogy between the two artists a bit further for Paolozzi too was fascinated by machines. They appear constantly in his work, but they don’t in Warhol’s. He may have wanted to be a machine, but he didn’t portray them. The point where the two artists’ interest in machines did coincide was when at almost the same moment they adopted screenprinting. A semi-industrial process, it fitted the bill as anonymous and mechanical. Warhol’s Marilyn, for instance, is a screenprint, but the way he changes the colour at will also demonstrates how this process can provide dramatic variations on a simple image. Paolozzi worked the same trick with one of his first screenprints, Metalization of a Dream, represented here in two versions with different colour arrangements. Neatly reconciling mechanical production with artistic invention, this way of working perfectly encapsulated the idea, coined in the 1920s by artists like Corbusier’s associate Amédée Ozenfant and the Bauhaus professor Laszlo Moholy-Nage, that the true art of modernity will arise from artists embracing the machine. Indeed, in the catalogue, curator Keith Hartley argues that what really unites Warhol and Paolozzi is their common debt to this idea. (Documents related to the early story of this machine aesthetic are displayed in the gallery’s Keiller Library.)

Warhol’s habitual use of photography, his own and other people’s, as the basis for his art develops this idea. In his Stitched Pictures, identical photos roughly stitched together, he found a way of marking the mechanical image as art without changing its character. He also continued to use screenprinting and until quite late in his career was still using it to make commercial posters. Some of them are really vivid.

Paolozzi’s series of screenprints, As is When, incorporates the imagery of early computer graphics, but, a masterpiece in the medium and a soliloquy on the life and thought of the philosopher Wittgenstein, it is very far from being simply mechanical. Indeed unlike Warhol, Paolozzi’s attitude towards machines was ambivalent. Early sculptures like His Majesty the Wheel, the Bishop of Kuban, or Four Towers, and related prints like Automobile Head, for instance, seem like totems of some primitive people in awe of the sinister mystery of machinery. The giant figure of Vulcan that towers in the lobby of the gallery is the descendant of these early works: consider where it puts us. Paolozzi was conscious of the machine’s power and the risk that we run of being dehumanised by it. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, portraying a world dominated by machines, was one of his favourite films.

Advertisement

Hide AdAlthough the Warhol display here covers the whole of his career, Paolozzi’s part of it is mostly limited to his earlier work, so the comparison is a little unbalanced, but even in his sinister, early figures, there is an undoubted sense of the spiritual, or at least of the unknowable, something that would have been quite foreign to Warhol. On his monumental sculpture, The Wealth of Nations, sited at the Gyle in Edinburgh, Paolozzi paraphrased Einstein, writing “Knowledge is wonderful, but imagination is even better.” It was an insight that is a constant in his work, even when apparently at his most mechanical. Warhol’s dedication to the machine aesthetic was purer. Perhaps really they are very different. Both are great. - Duncan Macmillan

Until 2 June