Violent anti-Italian riots in Edinburgh recalled 80 years on

Of all the abhorrent crimes inflicted on minority groups on home soil in living memory, few can rival the sheer inhumanity that consumed Edinburgh and elsewhere following Mussolini’s declaration of war on Great Britain on June 10, 1940 – eighty years ago today.

In shameful scenes that echoed Nazi Germany’s Kristallnacht attacks on Jewish-owned properties, large mobs of up to 2,000 people targeted Italian communities all over Edinburgh, looting and smashing up scores of shops to the point where, in some cases, not a single pane of glass remained, and verbally and physically attacking innumerable Italo-Scots.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile the Edinburgh police were busy rounding up and interrogating all Italian adult males, crowds attacked ice cream parlours and fish and chip shops across the city.

Leith Street and surrounding areas, where there was a large contingent of Italian businesses, witnessed riotous scenes after 10pm.

Plate-glass windows were shattered en masse by a mob that contemporary reports estimate at well over a thousands people strong.

Angry crowds paraded the streets and let their feelings known outside Italian premises, shouting, “traitor Mussolini” and singing the national anthem. Police made a number of baton charges, as sections of the crowd became more and more hostile.

Sporadic outbreaks were reported in other areas of the city, including Stockbridge, Dalry and Portobello and the fire brigade were called out on multiple occasions after stores were set alight at Picardy Place and Antigua Street.

Stragglers remained on the streets till the early hours of the morning.

They didn’t care that many of those Italo-Scots had been here for generations and some had even fought alongside them during the First World War.

State guidance had not exactly helped quell or prevent the anti-Italian hysteria.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFollowing Mussolini’s declaration, Winston Churchill, referring to so-called “enemy aliens”, had ordered authorities to “collar the lot”.

And, detailing the “combing-out” of the UK’s 20,000 Italians, many newspaper reports were every bit as culpable, effectively comparing an entire race of people to bothersome head lice that needed purged.

Despite the large number of attacks, just fifteen arrests were made on the first night.

Six people, three of them women, were taken to the Royal Infirmary to be treated for bruises and cuts to the head caused by people throwing bricks and stones and from flying splinters of glass. Just under 200 Italians between the ages of 16 and 70 were arrested in Edinburgh, from a total Italo-Scots population of around 400.

Eighteen men would later appear at Edinburgh’s Burgh Court for their part in the “disturbances”. They included Frank Slaven, a soldier in uniform, fined £1 for maliciously kicking in a plate-glass window of a shop at 158 High Street occupied by Nicola Valentino.

Others were fined and imprisoned for looting, among them five juveniles, linked to the theft of sweets from damaged shops.

The case of Primo Bosi

One famous arrest involved Mr Primo Bosi, a shop owner of Italian descent who occupied premises at 6 Union Place at the foot of Leith Street.

Although no shots had been fired from his under-attack premises, Mr Bosi was detained on a firearms charge after being found with an automatic pistol and 97 rounds of ammunition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt had been claimed Mr Bosi, 26, whose parents had been in Britain since the beginning of the century, was a member of the Italian Fascisti.

While admitting being in possession of a pistol and ammo was a “stupid thing to do”, Sheriff Jameson stated it was “deplorable” that because someone was of Italian extraction they should be the object of any antipathy.

Bosi was held in custody until June 18 and fined £1.

The anti-Italian attacks were condemned by MP Thomas Johnston, the Regional Commissioner for Civil Defence in Scotland, and it was stated that the people being attacked had “no sort of responsibility for Mussolini’s criminal lunacy”.

At a meeting, Mr A MacDonald of the Edinburgh and District Labour Council, said his cohorts were unanimous in expressing their “strong disapprobation” of the riots that had stained Edinburgh’s good name.

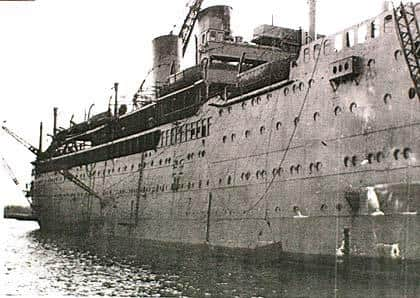

Paolozzi and the sinking of the Arandora Star

Tragically, many of the Edinburgh Italians arrested after June 10 were among the 734 British-Italian internees bound for Canada on board the SS Arandora Star.

The ship had barely made it past the Irish coast when it was torpedoed by a German U-boat on July 2, claiming the lives of 805 mostly Italian internees and German prisoners of war.

The sinking of the Arandora was especially heartbreaking for legendary Edinburgh-born sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi and his family.

The famous surrealist, who was interned at Saughton at the time, lost his father, grandfather and uncle to the incident. All three men drowned.

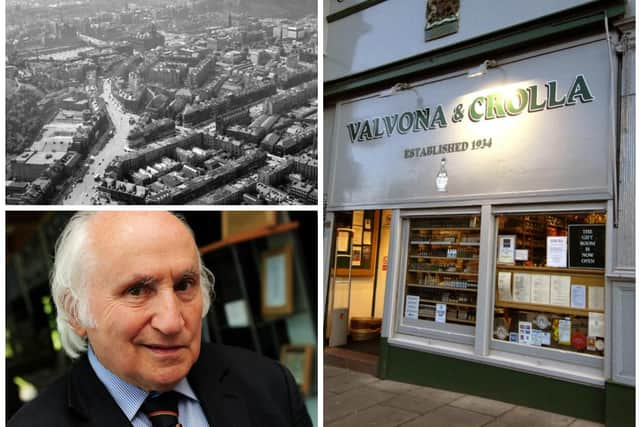

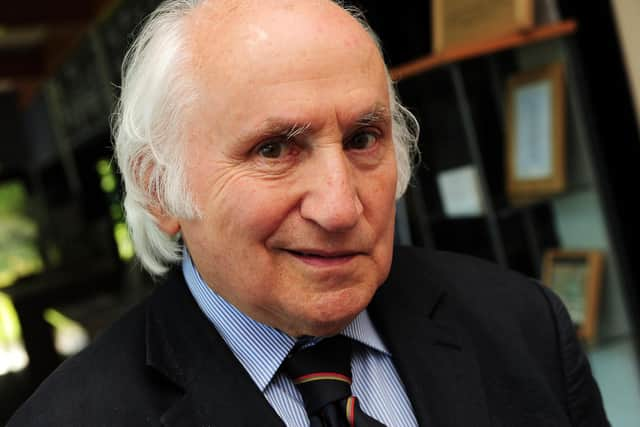

Richard Demarco: Anti-Italian riots changed my life

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne man with painful, first hand memories of the anti-Italian riots in Edinburgh is Richard Demarco CBE, co-founder of the Traverse Theatre and one of Scotland’s all-time leading lights in the arts world.

Brought up in Portobello with Italian heritage, Mr Demarco was aged nine at the time, and the incidents had a profound effect on him.

Richard was subject to much verbal abuse and a series of shockingly violent attacks because of his Italian lineage that would result in police escorting him to school for a number of years during the war.

Richard says the anti-Italian agenda in the UK and the racist abuse he experienced, while it caused him immense personal pain, served to spur him on in life and led to him pursuing a career in the arts.

He recalls: “The tenth of June 1940 is something that is deep inside my heart.

“It was a day of agonising reality, when my parents said you cannot now go to school, and you must be very careful when you walk the streets.

“Racism is one of the ugliest aspects of humanity, we are all Jock Tamson’s bairns, but, during my childhood, I was called an ‘eye-tai’ or a ‘wop’, and this went on till my mid-twenties.

“Don’t think for one second that I was in celebratory mood come the age of 15 and VE Day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This episode severely damaged my mother and father and pushed our family into poverty.

“That’s why, my whole life has been committed to using the language of healing, which is the language of the arts – the language that created the Edinburgh Festival.”

He adds: “The New Town, the famed first modern city in Britain, was inspired by Palladio. It’s Italian architecture that you’ve got in the New Town. Edinburgh’s future was built on the idea of an Italian model, and yet, in 1940, somehow the Italians were thought of as ‘foreign’.

“There’s now a generation of Italians who can’t remember any of this and are fully integrated. The Italians are no longer foreign.”

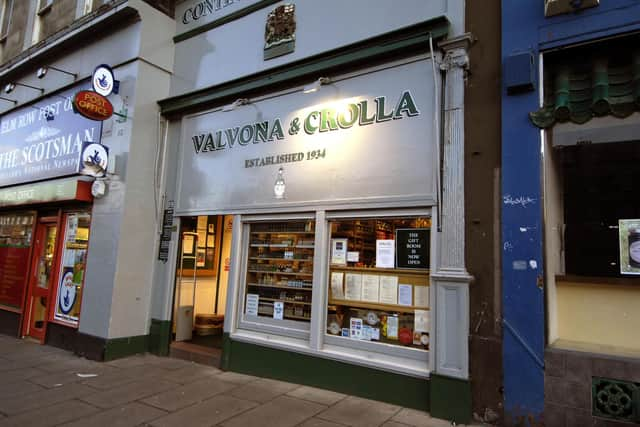

‘Boarded up’ city institution a testament to goodwill

Evidence of the anti-Italian riots that marred Edinburgh on this day in 1940 can still be seen on the facade at one beloved city institution.

Established in Edinburgh in 1934, the seemingly omnipresent Valvona & Crolla was situated, as it is today, on Elm Row, and very much in the eye of the hurricane on the night of the attacks. Eyewitnesses recalled wine flowing like blood from the premises, which had been smashed and looted.

While condemning the atrocious behaviour that befell the district that evening, Valvona & Crolla chairman, Philip Contini, is keen for the “goodwill of the majority” to be remembered too – not least those who came to the aid of his grandmother, Maria Crolla, who was on her own at the time.

“The men had been interned,” recalls Philip, 66, “and my grandmother was on her own with her children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But people, neighbours, came to help her clear up the mess. A local joiner came, offering his services for free, and told her, ‘don’t worry, we’ll board up the shop, keep it safe’.”

The joiner covered over the framework with a piece of hardboard for extra protection, lest the mob ever return.

“That hardboard is still there to this day,” states Philip.

Having received many licks of paint since 1940, the shop owners were even refused planning permission to remove the board during a refit a couple of decades ago, as the council deemed it an important artefact of Edinburgh’s history.

Philip says he is pleased it continues to “protect” the frontage.

He added: “It acts as a memorial from that time. That’s the beauty of it, while you’ll always find a minority mob element in the world, there’s this enduring thing that is the shopfront, which represents the goodwill of the majority.”

The story of the Crolla and Contini family and their immigration into Scotland in the early 1900s is in a book called Dear Olivia by Mary Contini, published by Canongate in 2006. Paperback. Available at www.valvonacrolla.com.

A message from the editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSubscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our local valued advertisers - and consequently the advertising that we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you helping us to provide you with news and information by buying a copy of our newspaper.

Thank you

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.