Remembering the Scots heroes of the Battle of Arras

The Somme campaign of 1916 had become politically contentious and those in power had no intention of fanning the flames of discontent and mistrust amongst politicians and public alike. In the House of Commons on 18 October, 1916, Sir Charles Trevelyan asked the government what the casualty figures were from July to September 1916. Responding for the government, the then Secretary of State for War, David Lloyd George, stated that the answer had already been given in a written response to Joseph King, MP for North Somerset. There was to be no public discussion on the Somme casualties.

In November, at the end of the Somme campaign, Lord Lansdowne wrote a memorandum to the prime minister and cabinet raising his concerns about the way the war was being prosecuted. He suggested that, despite the enormous human and economic costs to the nation, there was little, if any, hope of winning the war. He stated: “We are slowly but surely killing off the best of our male population of these islands. The financial burden which we have already accumulated is almost incalculable. We are adding to it at over £5 million per day.” In the same month he wrote to the Daily Telegraph publicly reiterating his concerns. Following the publication of his letter, Lord Lansdowne claimed he received many letters of support from serving officers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe government, acutely aware of the dreadful losses in 1916, wanted no more war of attrition. They needed a morale boosting success. Therefore, they insisted that any further offensives must be carried out in a series of step-by-step advances with strictly limited objectives capable of being called off if it looked like they were degenerating into another attritional struggle. With this understanding, a spring offensive was planned for 1917.

Unfortunately, the preceding winter proved to be very severe. Snow, frost and rain impacted on the transportation of men and materials, and conditions in the trenches and on the battlefield were atrocious. This led to delays in the evacuation of casualties. Stretcher bearers were hampered in their attempts to reach the wounded and carry them from the battlefield to Regimental Aid Posts – an onerous task at the best of times. Furthermore, the relay system that passed the sick and wounded from Aid Posts to Advanced Dressing Stations then on to Casualty Clearing Stations was seriously hampered by deteriorating ground conditions. However, despite these obstacles it was determined that the spring offensive would go ahead.

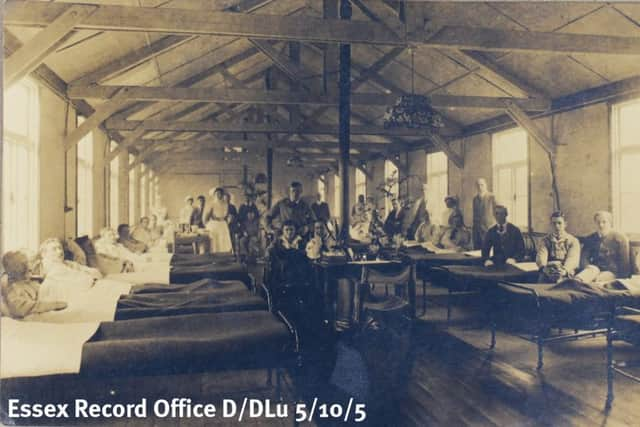

In preparation, Sister Kate Luard was sent to establish a 700-bed Casualty Clearing Station at Warlencourt. Casualty Clearing Stations were forward medical units designed to deal with the complex, immediate care of battle casualties. By 1917, they were at the forefront of life and limb-saving pioneering practice. Three years of industrial warfare had necessitated a change of strategy in the care and treatment of traumatic injuries. Since the outbreak of the war Luard had been involved in these developments and she was a highly skilled nurse.

Luard came from England but had strong Scottish connections. She had a great affection for the Scottish troops and regularly referred to them as her “beloved jocks”. In her diary entries between March and May she highlighted the appalling state of the casualties, the living and fighting conditions of the troops, and the taxing situations staff at Casualty Clearing Stations laboured under.

On 5 March, two days after her arrival at Warlencourt, she wrote in her diary: “Woke up this morning with half inch of snow on my bed covers and six inches outside.”

Her diary continues.

“10 March –The frost has broken and left us in a quagmire… The roads are bad enough but our camp is unspeakable. The field sticks to your feet and gradually works up towards your knees, and if your shoes are not anchored on by puttie straps you leave them behind. Tomorrow I will tackle it in ammunition boots.

“12 March – We have only one and a half pounds of coal per head per day, so when that is used up we have to go and look for wood to cook the dinner and boil the water. Colonel Gray from Aberdeen, the Consulting Surgeon from the 3rd Army, came and looked round yesterday and asked us how we liked being shelled… We have got to build and run our own hospital laundry… so far we have only seventy beds and mattresses, all the rest will have be nursed on stretchers.”

By 27 March Luard’s Casualty Clearing Station was taking in wounded men. On 10 April, she describes scenes that were becoming commonplace in the CCS following the launch of the Arras offensive.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Stretchers on the floor are back-breaking work. And one’s feet give out after a certain time, but as long as one’s head and nerves hold out, nothing else matters… Evacuation has been held up to-day for some hours and the place is clogged. The wards are like battlefields, with battered wrecks in every bed and on stretchers between the beds and down the middle of the floor.

“13 April – It blew and raged madly all Wednesday night, and there was deep snow in the morning. We have been getting the poor boys in who have been lying out in it for two days, and many of them have died since of exposure and gas gangrene.

“17 April – I have never seen anything like the state the men are in, mud caked on their teeth and under their eyelids.”

The Battle of Arras was launched with a five-day, 2,800-gun preliminary bombardment by British and Dominion Forces. High Command was determined that it would change Britain’s fortunes in the war and create a much needed wave of optimism. The Somme casualty figures, they insisted, would not be repeated.

On the home front women did what they had learned to do best throughout the three years of war, they waited: for the latest news, for letters from loved ones serving at the front – and even for the dreaded telegram from the War Office or letter of condolence from commanding officers or serving soldiers. How many women rehearsed in their mind a plan of action for their children should notification come from the War Office that their beloved husband and father had been killed in action? How often did they anticipate the arrival of a letter stating their beloved was missing in action, or had died of wounds, or was a prisoner of war? They must have wondered just how many times their menfolk would survive an action before they sustained life or limb-threatening injuries, or died of disease. How many Faustian bargains, superstitious practices, novenas, lucky charms, talismans and religious artefacts were called upon to ensure the protection and safe return of husbands, brothers, fathers and lovers?

There were, of course, any number of charlatans prepared to play on the raw emotions of the anxious and bereaved by offering, in exchange for money, “psychic interventions” with their loved ones. By 1917, the call on mediums and psychic healers had become so prevalent that, according to the Daily Mail, the parasitic practice had come to the attention of parliament and legislation was used to bring about prosecutions. The new campaigns in 1917, starting with Arras and Vimy Ridge, offered thriving opportunities for the exploitation of the bereft and vulnerable. There was profit in loss.

As an antidote to the angst that many women felt, support clubs were established for and by women from the earliest days of the war. The Tipperary League was a good example of women bonding together in common cause. The League and its clubs were non-sectarian and non-profit-making and they were affiliated to the Women’s United Service League Clubs. They were established for the benefit of the wives and other female dependents of men on active service in the defence forces.

The three main objectives of the clubs were to assist, instruct and entertain. For example, assistance was given to women who encountered problems with errors made in separation allowances or pensions. Instruction could be anything from teaching women to become skilled seamstresses or cooks or developing their first aid skills. Entertainment, was generally regarded as a respite from the daily concerns and worries about the war and how it could or did impact on family life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSocial clubs for soldiers’ and sailors’ wives and mothers were prominent in all areas of Scotland and were very much a grassroots movement. They were not run with the formality of the Tipperary and Women’s United Services clubs, but Scotland had a long history of pursuing alternative views and actions. Scotland knew what was best for Scotland and the war years were no exception. In early 1917, at Crieff, the Provost and his wife entertained 300 wives and mothers of soldiers and sailors to tea in the Porteous Hall. After the refreshments the ladies were entertained by a programme of songs, violin and piano duets, and recitations. It was claimed by a chronicler of the event that, “the women had buoyed themselves up with the hope that with the new year brighter days might dawn for them, and they might look forward to a speedy return of their husbands and sons. Instead of that, the outlook appeared darker than ever. There was much that was calculated to depress”.

Between 9 April and 15 May, Arras had the highest concentration of Scottish soldiers fighting in a single battle. Of the 120 battalions that made up the ten frontline divisions, 44 were Scottish. In April the total casualties received into medical units were 2,002 officers and 43,476 other ranks, which equates to 1,516 per day.

However, according to the medical services reports, the maximum number of wounded was during the first 24 hours of battle when 455 British and 6 German officers, and 9,719 British and 1,350 German other ranks were admitted to British front line hospitals.

On 27 April, Luard, according to her diary entry, was attending to a “handsome young Scot with one leg off”. He told her: “I’ve got two daughters and a wee son I’ve never seen.” Sister Luard knew he probably would not see his children because he had developed gas gangrene. As the young soldier lay surveying the human wreckage in the ward, he said to her: “Seems a pity nearly everyone has got to get like this before peace is declared.”

Dr Yvonne McEwen is Research Fellow at the WW1 Research Centre, The University of Wolverhampton, and Project Director, Scotland’s War 1914-1918