The radio pirates who brought the swinging 60s to Scotland

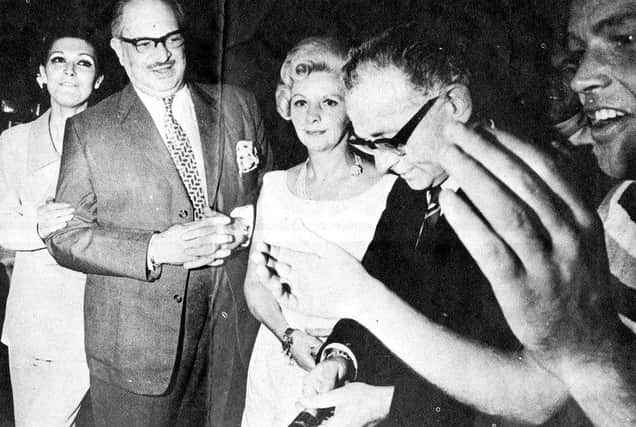

On a September day in 1966, Sean Connery, Rod Stewart and a host of other celebrities played a sold-out charity football match at Glasgow’s White Stadium.

Part of the former “Showbiz 11” football team, the celebrities were going head-to-head that day with a squad whose names might be a little harder to recognise today; Ben Healy, Tony Meehan, Stuart Henry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet as the players filed out of the stadium post-game, it wasn’t just the Showbiz 11 who found themselves mobbed by hordes of fans.

“I had my clothes torn off, my hair torn … I had to be rescued in a car and taken away," recalls Healy, who played against the star-studded Showbiz 11 team.

“At the time I thought 'oh my god, there’s Rod Stewart, there’s Sean Connery, what the hell are they doing with me’?”

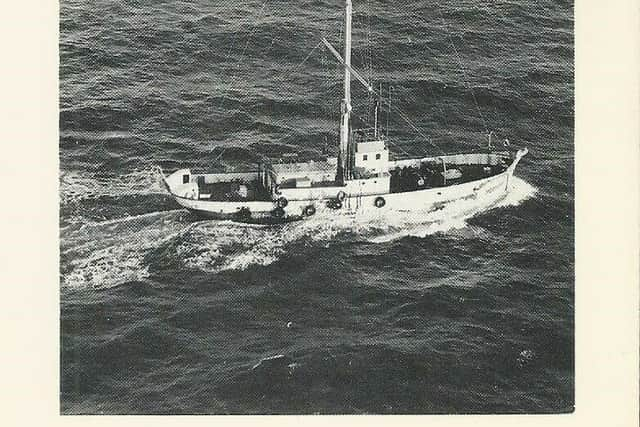

It was, he says, a “validation” of the trailblazing experiment he and his teammates were a part of at the time - an off-shore pirate radio station, beaming the sounds of the ‘60s to millions of listeners from a battered old light ship.

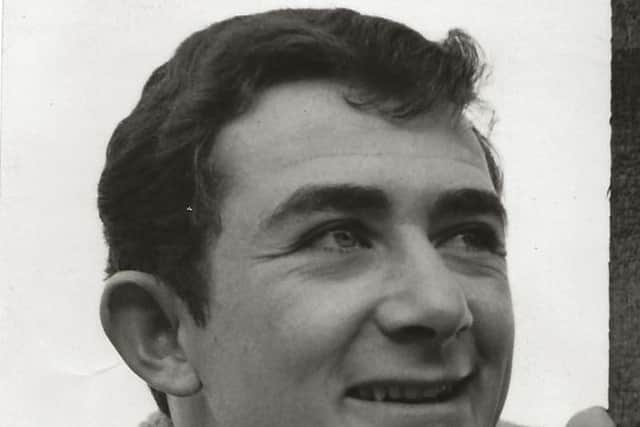

In just a year of spinning records on Radio Scotland’s airwaves, Healy alone would earn the accolade of “bringing Motown to the Mull of Kintyre”.

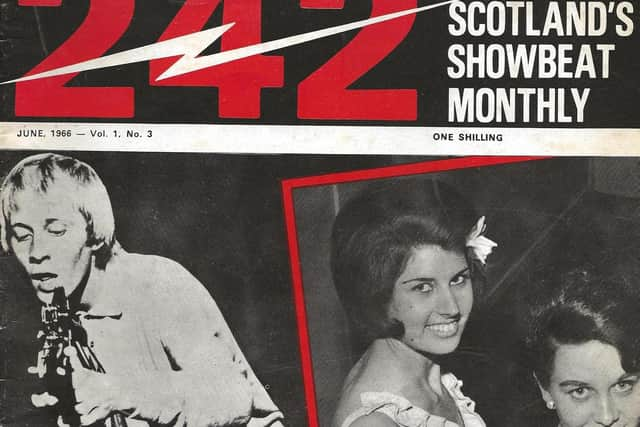

Launched on the eve of Hogmanay 1965, Radio Scotland made superstars of its DJs and left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of Scotland in its short time on air.

Broadcasting popular music and Scottish voices to millions, it filled the void created by the monopoly of BBC radio, which - at the time - left little room for either.

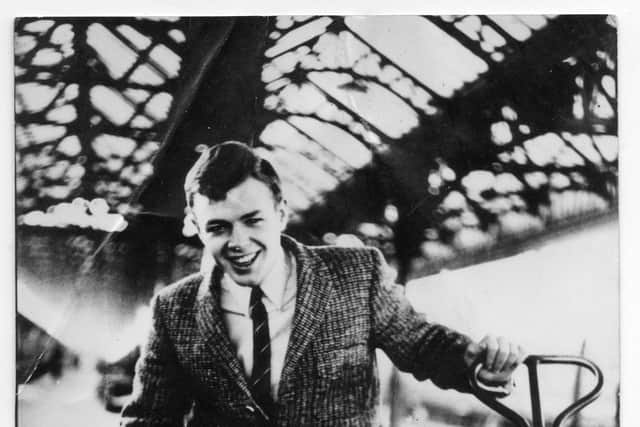

Though not the UK’s first pirate radio station – the famous Radio Caroline was launched in 1964 - Radio Scotland was the first to truly cater to Scottish listeners in an era before BBC’s own Radio Scotland, says Paul Young, whose voice was the first ever heard on the pirate station.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The only other pop station was the BBC and you never heard [requests] from St Andrews or Peebles … it was nearly always English,” he said.

"[Radio Scotland] was offering something new, something less disciplined than the BBC.”

Healy, originally from Ireland, had DJ’d elsewhere before arriving on board the creaky Comet lightship where Radio Scotland operated. He maintains the station was beloved by Scotland in a way that others weren’t.

“It was embraced by them [Scots] in a way that I’ve never seen … I never saw Radio Caroline or Radio London or any other pirate stations embraced like that,” he said.

"People loved those stations for love of the music - Scots embraced Radio Scotland for the love of it being Scottish.”

Most of Radio Scotland’s output fed the nation’s growing demand for pop records, though Jack McLaughlin’s Ceilidh show initially raised a few eyebrows for its unique take on the traditional.

“I was taken off [the Ceilidh show] after five days - people complained galore,” he said.

"Unfortunately for them, more people complained about me being taken off the programme than complained about me doing it, so I was put back on.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt wasn’t long, he says, before the show became one of the station’s most popular

Complaints were generally few and far between. However, from almost the moment it aired, says Young, Radio Scotland was an “immediate success”.

Fan mail and record requests came flooding in from the Borders to the Highlands, while letters from as far afield as Mexico, Scandinavia and Canada indicated the Comet’s 242m frequency was - unintentionally - reaching the ears of listeners around the world, and building an international fan base in the process.

Such was the volume of letters, says Healy, that DJs competed to have the biggest bags of mail - a process helped, in Healy’s case, by a fan club manned by his own mother.

“I got my mother to set up a fan club,” he said. “By the end I had about 3,200 people in it. I was getting bags of mail every other day, my mum would respond on my behalf.”

On the surface, it might all sound glamorous, yet life on board the Comet was often anything but.

“We had to get coal from the hold in buckets, the cabins were freezing”, explains McLaughlin, who has since written a book, Pirate Jock, about his experience on board. He recalls “getting up to read the news bulletin wrapped in a carpet” to stay warm.

Conditions could be dangerous too. At one point, says McLaughlin, the ship was battered by a force 12 hurricane. And while there “was a life raft on board”, he explains, “nobody knew how the thing inflated or even launched”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was, he maintains, “all part of the adventure”, which the DJs partially shared with listeners themselves - choppy conditions occasionally moved turntables and sped up or slowed down records as they played.

Life on board wasn’t all early mornings and rough seas, however.

“Occasionally, if we were daring enough, we would swim over to other boats”, explains McLaughlin, illustrating an occasion during the summer of 1966 when he and another DJ “swam across to a little yacht” for champagne, making it back on board The Comet without ever getting caught.

Though unpopular with the sitting UK Government, Healy recalls encountering little real trouble from the customs officers who were “told by London to give us a hard time”.

“I remember going through customs many times,” he said. “Some guy would say to me ‘we’re supposed to give you a hard time, but I wondered if you could play a record for my daughter Susie’.”

It wasn’t long, however, before the Comet’s fortunes turned. After moving to an anchorage off Troon, Radio Scotland was fined for illegal broadcasting. Their new location fell within UK territorial waters.

After some further, unsuccessful relocations, the station’s final death knell came with the introduction of a new Marine Offences Act in 1967, which outlawed pirate radio stations like Radio Scotland.

In spite of an outpouring of support - and even protests - from listeners, the station was unable to continue broadcasting. In August 1967, Radio Scotland aired for the very last time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust a couple of DJs remained on board as the last broadcast went out. Others attended a Radio Scotland clan ball in Glasgow with some 2,000 fans in attendance to say an emotional goodbye to the ground-breaking station.

“That was the most moving time of all”, says McLaughlin, remembering how station founder Tommy Shields, who died not long after the station’s closure, was “in tears” as attendees saw off Radio Scotland with a rendition of Auld Lang Syne.

In an age of on-demand digital streaming, it’s hard to appreciate just what was lost when Radio Scotland disappeared, says Healy.

“The BBC only played records seven hours a week because the musicians union was so strong, they wanted to play live music,” he said. “So you’re listening to some orchestra playing the Beatles, not the original record. When the pirates closed down, everyone was back to that.”

He points out that commercial radio, which ended the BBC’s stronghold on radio programming, didn’t arrive until 1973, several years after Radio Scotland’s closure.

Its legacy lived on nonetheless, say ex-pirates, in the programming that came afterwards.

“What [Radio Scotland] spawned was BBC Radio 1, 2, 3, it changed the BBC’s thinking about popular music – it was hugely influential”, says Young, who went on to work as an actor after leaving the station.

Many of the other pirates went on to successful careers in radio and broadcasting, though no jobs after Radio Scotland were quite as unique as life on board the Comet, says Healy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I got a job in radio in Canada, but it’s not the same,” he said. “It was like a regular job, the excitement of the sea isn’t there.

"[Radio Scotland] could never happen again, it just can’t be duplicated”.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.