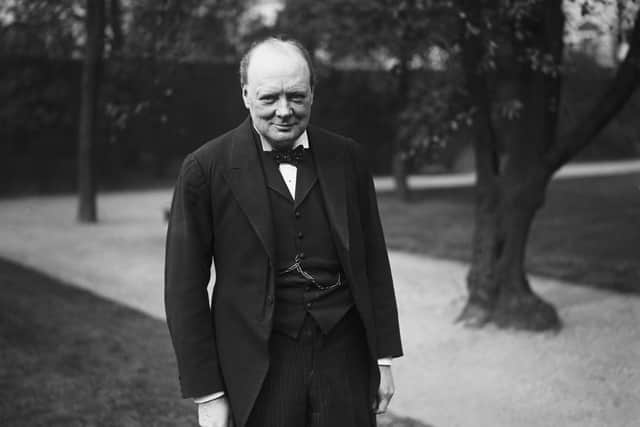

Why Sir Winston Churchill's exit from Dundee was far from a disgrace - remembering his tenue as a Scottish MP

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill was cast out from his Dundee constituency and sent back to England on November 15, 1922. The Scots hated him, and he hated them more.

There is just the slight problem that such stupendous reductionism is myth-making at its finest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf you search on Google, Churchill’s recurring quote about Scotland is "of all the small nations of this earth, perhaps only the ancient Greeks surpass the Scots in their contribution to mankind". The former prime minister never said this. And if the positive items are untrue, is it possible the hostile zeitgeist also deserves revisiting?

Conventional wisdom holds that Churchill lost the 1922 general election in disgrace. But he was not thrown out, nor was he a Liberal, but a National Liberal.

Churchill lost to Labour candidate E. D. Morel and Edwin Scrymgeour – the only Parliament member ever elected for the Scottish Prohibition Party.

The Liberals, of which Churchill was a leading light, were radically divided, split between the breakaway National Liberal Party, which supported the Coalition Government (1918–22) under prime minister David Lloyd George, versus the UK Liberal Party under his predecessor H.H. Asquith.

Attitudes to Churchill and the Liberal Party should be viewed parallel to Churchill's ejection from office in 1945. The party, not just the man, was rejected.

The only difference is the Liberal Party split, allowing it enough steam and confusion to continue until 1922 and no more. Churchill was defeated by Scrymgeour’s 32,578 votes to his 20,466, but it was only a 5,322 vote decrease from his majority of 25,788 in 1918 – itself an increase on his 7,302 votes in the by-election the year before.

The Liberal party was officially overtaken by the Labour Party, which became the main opposition to the Conservative Party. Churchill was to defect again formally by 1925, having switched his political affiliation from Conservative to Liberal in 1904.

In need of a seat in 1908, Churchill told his mother that Dundee was "a life seat and cheap and easy beyond all experience". It was common for MPs to represent constituencies to which they had little connection.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is worth underlining not only had Churchill been invited to stand in Dundee by the Dundee Liberals – although not unanimously – but from 1908 until 1922, Churchill was returned a total of five times.

In the subsequent century, all of this has become a blur. One Dundee historian concluded: "A statue of Winston Churchill here would be as welcome for many as a swim through vomit."

Despite serving as MP for nearly 15 years, it was only in 2008 that Mary Soames, Churchill's youngest daughter, unveiled a plaque commemorating the 100th anniversary of her father's 1908 victory.

In the Queen's Hotel, where Churchill regularly stayed, a second, privately funded plaque was installed around the same time and displayed a copy of Churchill's 1909 letter to his wife Clementine in which he complained: "This city will kill me. Halfway through my kipper this morning an enormous maggot crawled out and flashed his teeth at me."

Several key issues explain his reputational decline today. There is a tendency to conflate his bombast and aristocratic excesses, his ministerial profile, his politics and Englishness under an umbrella of disinterest for Dundonians and Scots.

The idea Churchill was outright hateful of Scots is a lie. The International Churchill Society has been trying to correct the record since 2018.

Before that, Churchill: A Seat for Life by Tony Patterson (1980) was the only dedicated book on Churchill and Dundee, alongside a smattering of academic essays. David Stafford’s Oblivion or Glory: 1921 and the Making of Winston Churchill (2019) is a riveting read on the subject. Andrew Liddle's new book Cheers, Mr Churchill! (2022) is not a revisionist take on Scotland, but a presentation of facts left in the historical ether about Scotland.

Once Churchill became MP for Dundee, he fully understood unemployment, poverty, slums and ill health. He became a champion of social as well as economic progress.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe supported the National Insurance Act of 1911 and a radical wave of social welfare policies, including unemployment insurance, labour exchanges, and education reforms. As Stafford notes, Churchill was appalled that many children were in "a savage and starving condition".

Churchill rarely visited Dundee more than once a year. That Churchill's home and ministerial work were over 400 miles away in London is hardly a disqualifier. In 1982, former home secretary Roy Jenkins said he was so unfamiliar with Glasgow that on arrival to campaign for the Hillhead by-election, he said the skyline was "as mysterious to me as the minarets of Constantinople" to Russian troops during the Russo-Turkish War.

He subsequently won. Sir George Ritchie, chairman of the local Liberal Party, was an excellent constituency agent for Churchill and kept him updated on the city's affairs.

During his time as a Scottish MP, he served in a series of senior ministerial posts: President of the Board of Trade, Home Secretary, First Lord of the Admiralty, Minister of Munitions, and Secretary of State for both War and Air.

In between, he fought in the First World War. The ministries deeply involved Scotland, and it was the 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers, that he led on the Western Front in 1916.

Andrew Dewar Gibb, the SNP's future founder and leader, was his adjutant in the trenches. He recorded Lieutenant Colonel Churchill saying Scotland had given him "his wife, his constituency, and his regiment – this was, of course, greeted with salvoes of cheering”. Churchill's second-in-command was Archibald Sinclair, who went on to become the leader of the Liberal Party.

The Dardanelles campaign in 1915 seriously damaged Churchill's reputation, but his 1917 by-election helped cast off many of the aspersions that he was solely to blame for the disaster. Despite his repeated electoral successes, Dundee was still a challenging political environment.

There were apparent differences between his aristocratic lifestyle and the lives of his constituents. Churchill complained to his wife Clementine he was "pelted with mud by angry ploughmen".

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven before the First World War, Churchill came to view the constituency as "a great trial to me". He had a famously acrimonious relationship with the original David Couper Thomson. When Thomson opposed the Liberal-Conservative coalition, Churchill began to "resent" the Dundee media for the way he was "attacked", and numerous public rows erupted.

In 1921, Churchill wrote to Lloyd George, confessing that he had become convinced there was "very great ground for complaint" about the Government's unemployment policy. One of Churchill's great trials was defending government policy on everything from women's suffrage, Ireland, the economy, the war conduct, and the Empire while representing the interests of his constituents. It is a familiar dilemma for Cabinet ministers today.

Much has been made of the detail that Churchill had been operated on before the election for appendicitis. He was too ill to participate in the campaign's earlier stages.

Unwell and unable to fight, he lost. "In the twinkling of an eye," he wrote for the Strand Magazine in 1931, "I found myself without an office, without a seat, without a party, and without an appendix." In truth, the tide was against the Liberal paradigm.

Churchill was without a seat between 1922-24, his only break between 1900 and 1964 representing five different constituencies. When he lost his seat, and in keeping with his character, he held no animosity: "My heart is devoid of the slightest sense of regret, resentment or bitterness. All my life I will look back with feelings of the deepest regard for Dundee and for those in it who stood faithfully by me."

In a 1942 speech in Edinburgh, Churchill reflected that "I sat for 15 years as the representative of Bonnie Dundee, and I might be sitting for it still if the matter had rested entirely with me … I still reserve affectionate memories of the banks of the Tay".

Churchill famously dovetailed the alleged acrimony by turning down a Dundee Freedom of the City a year later. But Dundee councillors did not make the offer unanimously, instead dividing along party lines, leading Tom Johnston, a Labour MP and Churchill's Secretary of State for Scotland, to advise Churchill to decline the offer, which he did.

It is beyond serendipitous that Churchill was born on November 30, 1874 – St Andrew's Day. Before Chartwell, Churchill nearly bought an estate in Scotland. The first of 1,000 biographies about Churchill was written by Alexander MacCallum Scott, his former private secretary and a Scot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChurchill’s time in Dundee was complicated, but Churchill is far more than a pantomime villain. His record is our history, and on this 100th anniversary, we would do ourselves a better service as a country to remember the man and not the myth.

Churchill happily borrowed from Charles Murray when he told his 1942 Edinburgh audience: "Auld Scotland counts for something still." And he was right.

- Alastair Stewart is a public affairs consultant, freelance writer, and chair of the International Churchill Society of Scotland

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.