Why Scottish unionists can celebrate the Declaration of Arbroath – Murdo Fraser

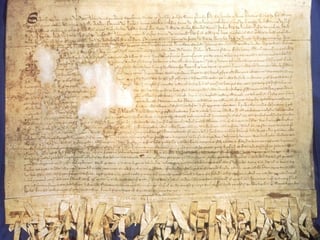

This week marks the 700th anniversary of the Declaration of Arbroath, the famous letter written by the Scots nobility to Pope John XXII in 1320. Its best known lines, delivering the stirring message, “While a hundred of us remain alive, we will not submit in the slightest measure, to the domination of the English. We do not fight for honour, riches, or glory, but solely for freedom, which no true man gives up but with his life”, we see printed on tea towels, mugs, t-shirts, and banners, prominently displayed at pro-independence marches and rallies.

The language of the Declaration has been an inspiration for Scottish Nationalists, and unsurprisingly has attracted significant interest over the last decade where constitutional politics have dominated Scottish political discourse. Inevitably, this intersection between history and modern politics, particularly in an environment as riven by division on the constitutional questions as today’s Scotland, has given rise to significant misunderstandings about the meaning and purpose of the document. There are numerous examples of the myths that have grown up around the Declaration.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor a start, the name “Declaration of Arbroath” is of relatively modern origin suggesting a status which would not be recognised by the document’s authors. Far from being the statement of Scottish nationhood often portrayed today, the letter was essentially a piece of propaganda drawn up at the insistence of King Robert the Bruce who was trying to win the Pope’s favour following his excommunication.

Nor is there much evidence to suggest that the Declaration was the inspiration for the 1776 US Declaration of Independence, as is sometimes claimed. This view is dismissed by Dr Alice Blackwell, curator of medieval archaeology and history at National Museums Scotland, who believes that the name “Declaration of Arbroath” is derived from the US Declaration of Independence, rather than being the other way round.

Divine Right of Kings

Equally questionable are the claims made in some quarters that there was something unique and distinctively Scottish about the promotion of the concept of popular sovereignty, or the principle that monarchy is contractual, and kings can be chosen by the people, encapsulated in the statement that should King Robert agree to English rule, he would be driven out and replaced by another king more to the authors’ liking. The notion of contractual monarchy, far from being an invention of 14th-century Scotland, has its origin in ancient times. As the Biblical books of Kings reveal, the Israelites of old were capable on more than one occasion of replacing a king who had lost their favour with someone entirely different.

Some commentators of a nationalist persuasion have even gone so far as to claim this an early example of Scottish exceptionalism, contrasting with a contemporary English belief in the Divine Right of Kings. This is simply nonsense. The theory of Divine Right, justifying the monarch’s total authority in both political and spiritual matters, did not reach its apex until the time of the Stuart kings. Ironically it was the first Scottish king of Great Britain, James VI and I, who was an evangelist for the Divine Right, set out in two tracts that he authored, The Trew Law of Free Monarchies in 1598 and Basilikon Doron in 1603, in the second of which he went so far as to claim near-parity with the Almighty: “The state of monarchy is the supremest thing upon earth, for kings are not only God’s lieutenants upon the earth that sit upon God’s throne, but even by God himself they are called gods.” It was devotion to the Divine Right that would lead James’ son and successor, the Dunfermline-born Charles I, to plunge three kingdoms into a decade of bloody civil war that would end with him being the only British monarch to lose his head after being convicted of high treason.

Scotland has a democratic say in UK Government

In reality, the Divine Right was as alien to English constitutional beliefs as it was to those of the Scots. Magna Carta, dating from 1215, more than 100 years before the Declaration of Arbroath, is explicit in its restriction on Royal power, setting out what the great 20th-century jurist Lord Denning described as “the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot”. It also explicitly provides, in Article 29, that no freeman can be condemned but by lawful judgement of his peers, a right which the current Scottish Government might well want to reflect upon in its enthusiasm to remove trial by jury in serious criminal cases.

Historical misconceptions aside, the importance of the Declaration of Arbroath can be recognised by all, regardless of political persuasion. It reiterates that after the Wars of Independence Scotland was a self-governing country, meaning that, unlike Wales and Ireland, Scotland became part of the United Kingdom not as a consequence of conquest by an English army, but rather as voluntary choice taken by the Scots Parliament of the time. It meant that two free and independent countries came together in a Union – one which in 2014 was comprehensively endorsed in a popular vote in Scotland in the largest democratic exercise most of us have ever seen. It is precisely because Scotland’s Union with England was voluntary that the Declaration of Arbroath can be celebrated today by unionists as much as nationalists.

We are not today, despite what some nationalist voices might claim, subject to English rule. In Scotland we have two governments; and we have a say in electing both of them. The Government in Westminster represents the whole United Kingdom, of which Scotland is a proud, significant and influential part. We are British as well as Scottish – and it is that British rule that we participate in, not that of some foreign power.

The Declaration of Arbroath may not have the historical significance that some claim for it, but nevertheless it is a document of great importance in Scotland’s story. Seven hundred years on from its creation, we should see it as a statement that can unite all Scots, not divide them.

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Frank O’Donnell

Editorial Director