When women in Scotland were cut on the forehead in the belief they were witches

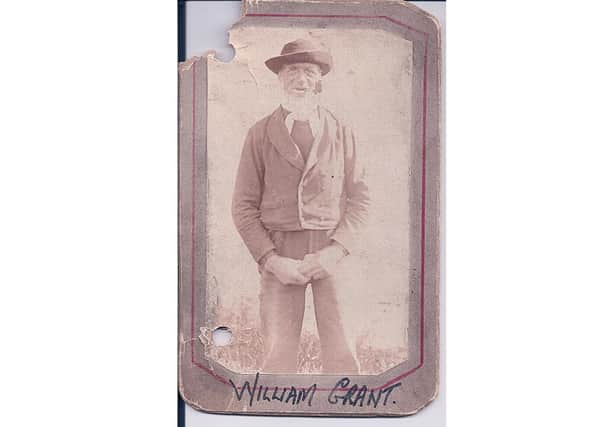

William Grant, a fisherman from Portmahomack in Easter Ross, ended up in court in July 1845 for the assault against the wife of a fellow seaman.

He believed the woman, likely to have been called Mary Munro and around 70 at the time of the attack, had “dark dealings in sorcery” and put him under some sort of curse.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot only did he blame the woman for the loss of his new nets and a loss of catch but his crew also refused to go out to sea with him while he was under her powers.

William Grant was arrested after the woman was injured and appeared at Tain County Court in July 1845. He admitted the assault, claiming he had been provoked, with his defence rejected and the case going to trial.

Information about Grant’s case is held by Tain and District Museum. Newspaper reports of proceedings record how Grant went to the woman's home and inflicted a deep cut “above the breath” – or above her nostrils.

It was believed that drawing blood in this way would lose the woman all power to injure or harm and would effectively draw out the devil.

A report of the case in the Inverness Courier said: “It would seem that a superstitious notion of this sort is prevalent among the Highland people, but the “cut” is generally made by a pin or needle

“In the absence of these, the prisoner used his knife, by which there was an effusion of blood for several hours, until the doctor arrived from Tain, and also confinement to bed for five weeks.”

The Sheriff addressed the prisoner at considerable length, the report said, with the fisherman condemned for the assault on a defenceless, elderly woman.

He was also reprimanded for “exposing the groundless superstition which prompted him to such an act of cruelty”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGrant was sentenced to three months imprisonment at Dingwall.

The report added: “It is hoped that the punishment of Grant will have a salutary effect on the fishermen and villagers of whom, it is said, a great proportion entertain the same superstitious belief in witchcraft.”

Indeed, Grant was not alone in his superstitions although his assault on a woman amid accusations of witchcraft perhaps came later than most.

Another case of a Portmahomack fisherman cutting “above the breath” is recorded in JM McPherson’s compedium Primitive Beliefs in the North East of Scotland.

The fisherman, whose boat wrecked while out at sea, believed his ‘jilted sweetheart tried to drown him by her magic art" and in response cut a cross into her forehead.

"The man was punished for assault, and the woman, ever after, wore a black band around her forehead.”

At Corgarff in Aberdeenshire, the method of how to cut a suspected witch was well known.

“Take a silver pin, coceal it between the fingers and the thumb of the lef hand, try to meet the witch in the morning, pass her on the right side; in passing draw blood from above the eyes. Keep the pin covered with blood and the witch has no power over you,” the account said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEarlier, a nail from a horseshoe was the preferred tool for making the cut and sometimes tree branches were used.

At Elgin in 1647, charges against accused witch Janet Cowie included a claim that she left John Purs unable to keep any food in his stomach for nine weeks.

“One half of the day, he did sweat and the other half he did tremble, and did never recover till he bled her with a tree,” the account said.

It is claimed that, he recovered immediately afterwards.

In 1750, a case came before the presbytery of Tain after three men dragged a woman and her daughter out of bed and laid them on the floor.

Two of the men held the women while the third “scored and cut their foreheads with an iron tool, calling them witches, according to McPherson’s account.

One of the men believed that his consumption was caused by witches, although cutting the women offered him no cure.

Another account from Braemar detailed how a young man who became ill after “offending a witch” sought to cut her “above the breath”.

One witness recalled: “And I think that the funniest thing I ever saw was the lad watching like a cat for his opportunity, and when he got her in a suitable place, tearing the mutch off her head an’ scratching her face till the bleed cam.”

It is said the man then recovered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe superstion of cutting the woman held firm for centuries. During the clan era, it was considered good luck to meet an armed man. If a barefooted woman crossed their path, she was seized with blood drawn from her forehead.

It is said the practice had its roots in German folk tradition.

Witch hunting came in various waves across Scotland after the passing of the Witchcraft Act in 1563, which made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes.

Records detail witchcraft charges against some 4,000 Scots, the overwhelming majority of them women

The 1563 Act was repealed in 1736 but, as shown in the case of William Grant, fear and superstition held firm for some for decades therafter.

A message from the Editor:Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director