What impact has the 1990 City of Culture had on Glasgow - 30 years on?

Thirty years ago, Glasgow was named European City of Culture, following places such as Berlin, Amsterdam and Florence to take the title.

It spun Glasgow, long strained by decline and poverty but a place unflinchingly full of human spirit, on its axis with the many legacies of the year-long event still felt today.

For young actor John Gordon Sinclair, star of eighties screen classic Gregory’s Girl, the 1990 award redefined the city and its people.

He recalled: “At the time, I had been down in London for eight years . I remember meeting my agent in 1980 for breakfast at Central Station and he said to me ‘if you want to make a go of this, you have to move to London’. That is what happened.

This article was brought to the reader by Glasgow Distillery who are celebrating the city’s rich heritage with their new Malt Riot Blended Malt Scotch Whisky.

"What the European City of Culture did was make it feel like you didn’t have to do that any more.

“There was so much happening around 1990 that still resonates so strongly for me,” said Gordon Sinclair. “There was German reunification, Thatcher was on her way out.”

And then there was the European City of Culture in the place he called home, a place he had “never been away from long enough to miss”.

The memory of Glasgow coming out on the streets, connecting with free concerts, with plays and with art exhibitions, sticks strong in the mind for the actor.

He said: “It suddenly seemed like anything was possible. It felt there was a new confidence in the place. I may be looking at it through rose-tinted glasses but it seemed that people were much more happy to speak about culture, to relish it, to bring it into your life and feel confident talking about it.

"For a long time, I suppose, Glasgow was seen as second to Edinburgh when it came to the arts because it had the festival. But in 1990, Glasgow just said ‘we can do this’.”

Bob Palmer, the man who led the event as festival director, earlier described his job as “managing a volcano, overflowing with the hottest talent and the most incredible excitement".

International stars were drawn to perform in the city in 1990, from Pavarotti – who had 12,000 fans at the SECC bouncing – to Frank Sinatra and the Rolling Stones.

The Age of Van Gogh exhibition at the Burrell Collection, where insurers underwrote the 18-piece collection for £200m, remains the most successful in the history of the venue.

In George Square, Texas, Wet, Wet, Wet and Deacon Blue represented the city’s love of music to the nation with the free concert broadcast on Channel Four.

Down on the Clyde, a 67-feet wide model of a ship was built in a shed at the Harland and Wolff yard where an audience of 1,200 gathered for the play The Ship that climaxed with a spectacular recreation of a launch onto the river, with real shipyard workers used in the production.

Up in the north of the city, the play 'Ruchazie, Ruchazie' unfolded on the streets to tell the story of the gangs that had the community in their hold. The 'Call that Singing' event brought together a choir of a thousand Glaswegians, aged nine to 90.

The City of Culture became a powerful example of culture-led regeneration for cities. Where Glasgow led, cities from Manchester to Barcelona followed.

Professor Alan Dunlop, an architect born and educated in Glasgow who co-founded a practice in the city in 1994, had graduated from the Mackintosh School of Architecture and moved to Manchester just before Glasgow’s award of the European City of Culture was announced in Brussels in 1986.

He said: “Manchester was astonished that Glasgow got it – and I think a lot of Glaswegians were astonished too. Athens, Amsterdam, Berlin and Florence, these major world cities, had earlier held the title and then in 1990 it was Glasgow. That took everyone by surprise.

“We were just getting out the horribleness of Glasgow in the 1970s and 1980s and it is hard to underestimate the positive effect that winning the European City of Culture had.

"There is no debate that Glasgow changed as a consequence, physically, economically, socially. It is actually incredible to think how much it has changed in a relatively short period of time and what kickstarted that was the European City of Culture.

"It gave the city and international profile but it also made ordinary Glaswegians stop in their tracks. I think it made a lot of people think that anything is actually possible.”

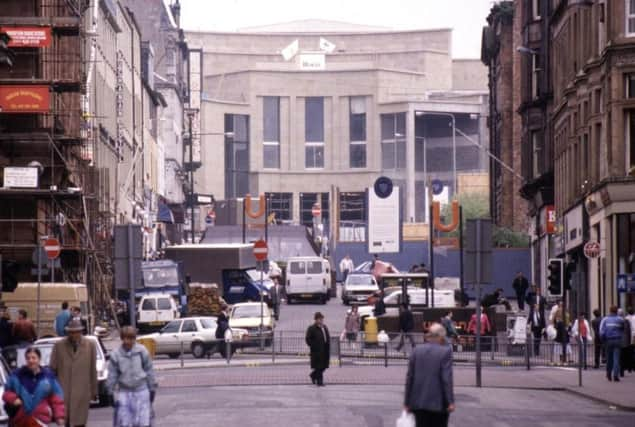

While a psyche changed for many in the city, the physical legacy of the event was set in stone. What is now the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall was built at a cost of £27m. The former Museum of Transport became one of the coolest performance spaces in Europe – The Tramway.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Scotland Street School was turned into a Museum of Education and the House for an Art Lover was built in Bellahouston Park from his original drawings.

Renovation of 22 massive arches under Glasgow Central also came, with the Glasgow’s Glasgow exhibition then stage. Thousands of objects telling the story of the city, from its industrial riches to its steep decline and its contemporary renaissance, were placed.

Benches were placed in the city centre to allow shoppers to take a seat in the theatre of the street. More than a hundred buildings were blasted free of soot with many of them floodlit.

Upgrades were made to a string of cultural buildings such as Glasgow Film Theatre and the Burrell Collection.

There were serious concerns that the disadvantaged of the city were left behind by this spending spree. Poor quality housing and the prospect of jobs for all continued to slide but the believers insisted that the event brought investment to the city, leading to long term gains, and allowed it to present a new side of itself to the world.

And people came. Glaswegians used to joke that a visitor to their home town was someone who was lost on their way to Edinburgh. Even tourist bosses admitted that, up until the early 1980s, Glasgow was a place to miss. But the effect of the 1990 event was real. Tourists rose from just 700,000 in 1982 to 3m that year. The SSEC, which opened in 1985, was booked up to 1997 following the European City of Culture award.

City bosses and cultural leaders revelled in the headlines around the world. In the Sydney Morning Herald, they wrote of Glasgow’s reputation as Scotland’s ‘biggest, dirtiest, slummiest, most violent city’ being no more. “The ghost of an ugly past has been laid to rest,” the newspaper said.

In the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, they wrote of “the ugly duckling of Europe” turning into a swan. In the Vancouver Sun, the view was that this ‘tough industrial town’ was ‘now a cultural mecca’.

Anything, it seemed, was indeed possible.