The seized Jacobite money and land that helped build Scotland

Forfeiture of the often vast estates and income of the key Jacobite figures of the 1745 rising was designed to root out, once and for all, the old Highland influences and any lurking danger to the stability of the state from the supporters of the Stuart cause.

The Duke of Cumberland, who led British forces at Culloden and the ultimate defeat of the Jacobites, was an enthusiastic supporter of the forfeiture regime.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Moved by hate and fear of Scots and particularly of Highlanders, he declared after April 1746: “I tremble for fear that this vile spot may still be the ruin of this island and our family,’ according to an account in Annette Smith’s Jacobite Estates of the Forty Five.

Money stripped out of this land through rent and sale of produce was to be ploughed back into improvements in the Highlands with infrastructure projects to diversify the economy, lessening the influence of the clan, as well as contribute to wider social benefit.

But Professor Murray Pittock, British cultural historian at Glasgow University said the true intention of forfeiture was clear.

He said: “Really this whole idea of improvement was window dressing. It was really hit or miss.

“The whole reason for forfeiture was, quite transparently, to punish those who had taken part in the 45.”

The results of the Edinburgh-based Board of Forfeited Estates were mixed at best.

A total of 53 estates were surveyed following the Vesting Act of 1747 which allowed the Scottish Court of Exchequer to value land and possessions of those accused of high treason.

The rents, issues and profits of the estates were to be brought for the Use of His Majesty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFollowing that, the Annexing Act five years later went further. “Clear rents and produce should be applicable to the purpose of civilising the inhabitants upon the said estates, and other parts of the Highlands of Scotland, the promoting among them the Protestant religion, good government, industry and the principles of duty and loyalty to his majesty... and nothing else,” the legislation said.

But the forfeitures, which had been tested after the 1715 rising, were fraught with difficulty and led to often miserable outcomes, with deals being cut and inconsistency in they way the punishment of the Highlands was served. There were dangers too.

One surveyor sent to the Highlands noted the and his men carried out their duties at ‘considerable rique (sic) of personal injury and danger.”

Complaints about the weather as they ventured from Edinburgh into the Highlands were common. The same surveyor spoke of sleeping on straw in his clothes while on the job and of being ‘not certain when we lay down but our throats might be cut before morning.”

Colin Campbell of Glenure, the government-appointed Factor who collected rents from the Clan Stewart of Appin lands in north Argyllsshire, was shot in the back by a marksman in May 1752 with the case known as the Appin Murder.

Tenants who had lived and worked under their landlord were often resistant to dealing with new government officialdom. Some were still paying rent under the old system. Of course, they did not want to pay it twice.

“Even if you got into the estates, the tenants could be obstructive. People often didn’t want to co-operate,” Professor Pittock added.

Projects like the Forth and Clyde Canal – which received the equivalent of £11m at today’s values – plus the building of roads bridges, harbours, inns, were all funded by the forfeited estates programme.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Royal Edinburgh Hospital in Morningside, which treats mental health patients, was built after almost £500,000 in today’s money was given from the forefeited estates fund.

General Register House, the repository for national records, was built with a grant of £12,000 – or around £2m at today’s values.

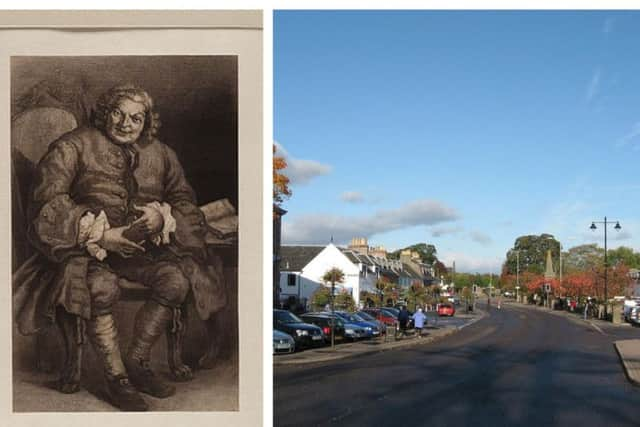

Meanwhile, towns through the Highlands were reconstructed, including Beauly in Invernesshire. One agent described it as such: “Though the common people are generally lazy, ignorant and addicted to drinking....the site itself could ‘not miss to attract strangers of different professions from many corners and would consequently soon diffuse a spirit of trade of industry, as well as promote agriculture through all this extensive country.”

Support and expansion of the linen industry were also supported by the Board for Annexed Estates, with around £6m at today’s prices to be spent on three manufacturing stations across the Highlands.

Following the passing of the Annexing Act in 1752, only 13 of the original 53 surveyed were actually annexed, with funds going to the Exchequer.

They were Arnprior, Ardsheal, Barnsdale, Callant, Cluny, Cromarty, Kinlochmoidart. Lochgarry, Lochiel, Lovat, Monalty, Perth and Struan.

The fate of Lovat estate illustrates the inconsistency in the way Jacobite families were treated by the state.

Lord Simon Lovat, known as the Old Fox, was beheaded at Tower Hill in London in April 1747 for his support of the Jacobites during the 1745 rising. He was also working as a British Government spy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis heir, also Simon Fraser, also fought at Culloden but escaped punishment and went on to raise a Fraser regiment from the land which had been seized under the forfeiture programme.

But with the fighters serving the British Army in Canada,some of the forfeited estate was granted back to him by an Act of Parliament in 1774 in recognition of his military service to the Crown.

Professor Pittock said: “Simon Fraser was brought onto the field of Culloden and fired a few shots in the air.

"Afterwards, he spent his life redeeming himself to the British Army. Although the estate was forfeited, he was allowed to raise men off his lands because they were to fight for the British Army and in the end he got a special deal. He was given the estate back in 1774 because he had been such a good boy.”

He was also given favourable terms for paying back the public funds used to clear debts of the Lovat estates at the time they were taken over by the government. He was given 10 years to give the money back at three per cent interest while others were given five years to pay at a five per cent rate.

The standards of improvements to the Highlands estates also wildly varied. Lord Kames, an advocate and agricultural improver, said large amounts of money spent on the Highlands and annexed estates was ‘no better than water spilt on the ground’.

When it came to debate the return of the annexed estates, Lord Sydney said it was ‘easy to distinguish’ the annexed estates because of the bad condition they were in compared to other men’s estates and for the almost total neglect of their cultivation,” according to Smith.

There was little opposition to returning the estates to the families of the 1745 rebels, with some genealogical research required to establish the rightful heir in some cases. By 1784, the experiment was complete.