The Scots slave owner 'celebrated' for killing a Caribbean national hero

Little has been known about Alexander Leith, who at 19 left his poverty-stricken family in Aberdeenshire to take up the offer of land in St Vincent , part of the Ceded Isles handed from the French to the British in 1763.

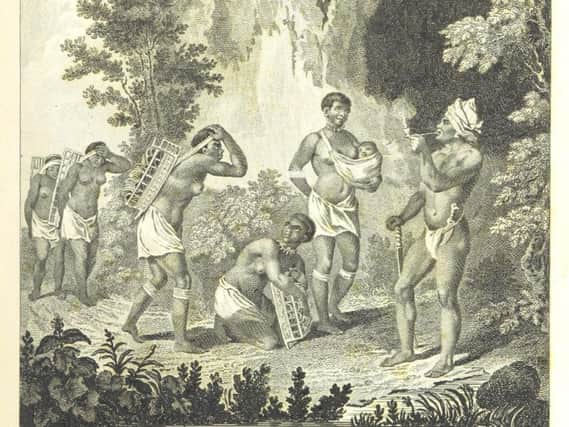

Now, new research has cast light on Leith and the hundreds of other men and women, mainly from the North East, who ventured to these islands to exploit the booming trade in sugar, slaves and perhaps tobacco and indigo.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeith, who went on to lead a local militia, was later hailed for killing Chatoyer, leader of the Garifuna people, in 1795 as the Scots sought to increase their territory on the island.

Leith’s memorial in St George’s Anglican Cathedral in Kingstown notes the “distinguished part” he played in the Carib war, with the Carib chief “falling by his hand”.

But for someone so noted in St Vincent history, the story of the man from the Shire who worked as an attorney for plantation owners, owned at least 10 slaves himself and had two sons t an enslaved woman, remained largely elusive.

Dr Désha Osborne, who lectures at City University of New York and currently an IASH fellow at Edinburgh University, said: “All that remains of Leith in St Vincent is located with his remains – a note on a memorial slab of the cathedral. That was it.

“Around the time of St Vincent’s independence in 1979, a red carpet was place over the slab in a deliberate act of disrespect to Leith and seemingly out of respect for the memory of Chatoyer.

“While all the other memorials to colonial administrators, soldiers and prominent European families are still visible, Leith is the only one covered .There have been no studies until now on the life of this man.”

Leith hailed from the large and extensive family which held properties such as Leith Hall near Huntly, Glenkindie House, Arnage Castle in Ellon and nearby Fyvie Castle.

But while being born into one of the area’s most wealthy lot, a family disagreement left his parents financially ruined and entirely dependent on remaining allies within the Leith fold. Sporadic crofting work was undertaken to survive.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1771, Alexander left for the West Indies, with advertisements for opportunities in the Ceded Isles well-advertised locally. In St Vincent, a circle of men from the North East area were already in operation, including Major William Lumsden of Cushnie, Murray Farquharson of Coldrach near Ballater and Macduff Fyfe from Cabrach.

Leith, who was appointed as an attorney to plantation owners, quickly gained influence among his men. By 1795, he took the role of captain of the local militia as the Second Carib War broke.

Intriguingly, Leith’s role in the death of Chatoyer was memorialised in a poem called Hiroona, which is written in a Walter Scott-esque mash of historical fact and romantic imagination.

It was this poem that led Dr Osborne on the trail of Leith in a bid to separate the truth from triumphalism.

The research also brought her face-to-face with her own family history. With both parents hailing from St Vincent, her mother’s grandmother, called Princess Rose, had a Scottish father and is known to have travelled to Scotland in the very early 1900s, when aged just five.

Dr Osborne found that the Scots legacy on St Vincent was vast, not least because an estimated 30 to 40 children born to enslaved women were fathered by Scots.

Leith’s sons, John Munro and Patrick Haffey, were enslaved like their mother until Leith’s death in 1799, when they were given manumission. The three were given a combined inheritance of around £1,000 with John sent to Aberdeen for schooling.

Both sons are known to have later bought land and slaves in St Vincent, with their mother, Roselind, later sold one of these plantations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Osborne said: “When I started looking into this, I was shocked, because we just haven’t known of these family stories and we don’t know how much they are acknowledged as part of people’s family history.

“I was really quite overwhelmed, as these stories are also part of my own family story. It also shocked me how many people were from one part of Scotland. I found myself calling my parents and asking them, are there still Leiths, Cruickshanks, Gordons and Farquaharsons on St Vincent? The answer was always yes.

“I thought about all the people who I have met during the course of this research, people from North America and Canada, who are so proud of their Scottish heritage, they learn Gaelic and they wear tartan, but it is not the same for a Caribbean.

“We just don’t know if it was a heritage that was embraced – or if it was wanted. We don't know what there is to celebrate."