The once mighty Pictish fort which holds on in the face of destruction - for now

From major fire to demolition and now the threat of coastal erosion, the once mighty Pictish fort at Burghead in Moray has long been under attack.

But a picture of life and times at this elite coastal site overlooking the Moray Firth, where the defensive walls stood at least eight-metres wide in parts, continues to build due to the work of archaeologists at Aberdeen University who have completed their third summer of excavation at the site which is believed to have been a major power centre of the Pictish Kingdom of Fortriu.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere, Pictish leaders are likely to have gathered while a significant population lived side-by-side with a fleet of vessels possibly harboured in the shallow anchorage below.

With the fort set on fire in the 10th Century, a time of Viking raids along the Moray coast, and the seaward defences later demolished during the construction of Burghead in the early 19th Century to provide stone for the modern harbour – it was long assumed that little archaeological remains of the fort remained.

But with ongoing discoveries of new buildings, metalwork, weaponry and decoration, a picture of a complex settlement at Burghead – an important site between 500 and around 1,000AD - continues to emerge as archaeologists work against rising tides and the impact of coastal erosion.

Professor Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen said: “Burghead is the largest promontory fort we know of the Pictish period – around 5.5 hectares including the defences now lost under the modern town.

"It was a hugely defended site with ramparts around 8m wide and 6m high. It is likely to be an elite defended settlement.

“Burghead is the largest and most sophisticated defended settlement of the later Pictish period from the 7th-9th century AD. Some of the elites of society must have resided there, but it must have also been an extensive community given how large the site is and the resources required to build it.

"It could well have hosted royal visits or been an elite residence but there would have been multiple such residences within Pictish society.”

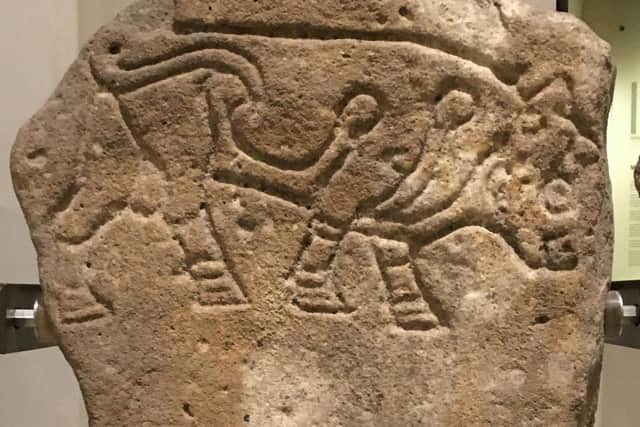

Three new buildings were found at the complex this summer, as well as craftworking areas. The discoveries add to the growing evidence of everyday life at the fort, which was once decorated with the Burghead Bulls, around 25 carved stones which were discovered during the 19th Century destruction of the fort. Some believe the stones may have lined a processional route into the heart of the complex and others believe they may have been linked to a fertility cult. Today, only six of the stones survive and are split between Edinburgh, Elgin and London.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn what the bulls represent, Dr Noble added: “The most basic principle might be that bulls are leaders/masters of the herd – so may be very basic symbolism of power here, but bulls were significant in both pagan and early Chrisitan symbolism. It could be they belong to an early part of the fort sequence – possibly even in a pagan or transitional context.”

The well at Burghead has also been linked to paganism and its sacred connotations of water with theories emerging in the 1980s and 1990s that it may have served as a shrine where ritualised drownings may have occurred, although many different interpretations have been made.

The well, a rectangular rock-cut chamber with a curved pedestal and a stone basin in adjacent corners, is surrounded by a paved walkway and considered one of the most elaborate of its type.

Dr Noble said: “I think on a very basic level it would have been a major water sources for an important population centre, but the quality and character of the construction is unprecedented in forts of this period.”

The building of Burghead has been described as a hugely complex feat of engineering that demanded extraordinary levels of manpower. A timber-laced wall, which stood more than six-metres high and served as a massive defensive barrier, was earlier found in the lower citadel of the fort.

Burghead also emerged at a time when coastal sites and maritime networks were likely regarded as important to Pictish political success.

On the fort’s geographical location, Prof Noble added: “It’s a natural defensible location, but also a hugely connected location especially for maritime orientated societies.

"We know the Picts must have had a fleet of some kind and given Burghead is a natural anchorage, one of the few in this stretch of coast, it may well have been an important sea node for Pictish sailing vessels.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt may have been at a site like Burghead that Bridei, the 6th Century King of the Picts, maintained dominance over the Orkney Isles, according to Dr Nicholas Evans, who co-authored The King of the North, The Pictish Realms of Fortriu and Ce, with Professor Noble.

The fire which razed the fort in the 10th Century helped to preserve the wooden remains through charring when normally they would have just rotted away.

Prof Noble said there were no contemporary references that linked the fire that razed Burghead to the Vikings, with the theory only laid down in folklore and speculation.

He added: “ We might yet find the Vikings at fault but there is no smoking gun as of yet. Having said that the timing of abandonment is intriguing and is certainly associated with the dramatic changes of the Viking Age.”

Today, it is changing sea levels on this stretch of coast that poses the biggest threat to Burghead.

Prof Noble said that the excavations at the site, which are funded by Historic Environment Scotland and the Leverhulme, were primarily a “rescue project”.

In 2018, the complex timber wall was one to one-and-a-half metres away from the erosion face. This year, it sits right on its edge.

Prof Noble added that around 50 per cent of the most threatened area of the fort had been saved with it hoped to finish the project in the next three to four years, funding allowing.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.