The Edinburgh medicine cabinet and the city high life

The medicine cabinet houses a dark part of the country’s history.

Found at The Georgian House in Edinburgh, a classic 18th Century New Town property run by National Trust for Scotland, it contains everything from castor oil to chloroform and laudanum, all of which would have been vital components of a 19th Century household medical kit, particularly laudanum.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLaudanum was a mixture of opium and high-proof alcohol that would have been taken to cure and ease all manner of symptoms, from diarrhoea to teething pains in children.

In various forms, opium has been used as a painkiller or a sleep aid for thousands of years, and was known to the Ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians.

By the early 18th century, opium (in its laudanum form) would have been a staple in every doctor’s bag and every household throughout the UK. It could be bought from a corner shop or a chemist and until 1868 was as easily obtained as tea or coffee.

The more dangerous medicines in this box are labelled ‘poison’, demonstrating that very early on people realised that opium was unsafe. However, it wasn’t until 1916 that opium addiction was recognised as a public health problem.

A simple search of the British Newspaper Archive shows the prevalence of laudanum use in Edinburgh society. Countless poisonings, accidents or attempted suicides are reported in newspapers between 1700 and the early 20th century.

They include a case reported in April 1898, when a young woman pleaded guilty at Edinburgh Police Court to behaving in a disorderly manner and attempting suicide by drinking a quantity of laudanum.

“An agent states the accused took the drug to frighten a young gentleman who had refused to implement a promise to take her to Kelso races,” the report said.

An 1872 report on the death of a man who shot himself dead in a “house of ill fame in Edinburgh” notes how a “well dressed and good

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adlooking” woman had slept with the man after swallowing a dose of laudanum in a druggist’s shop in St Andrew Square.

Meanwhile, the death of Reverend W Wyse, a minister at Crosshouse in Ayrshire, died in Edinburgh Infirmary after taking an overdose of laudanum in a city hotel in 1894.

The problems were widespread and affected large numbers of the population. Laudanum was cheap and easily accessible, and so was a popular means of suicide, but it was also unregulated and the cause of many accidental overdoses.

However, these were not the only dangers. Medical use often turned into habitual use, and many people began to take the drug recreationally.

Opium was cheaper that alcohol, and the working classes saw it as an effective hangover cure. By the 1870s and 1880s addiction was so widespread that a new word to describe the phenomenon entered the English language – ‘morphinomania’, named after Morpheus, the Greek God of sleep and dreams – a rather romanticised name for a dreadful addiction.

By the early 19th century petitions called for the sale of laudanum to be more strictly regulated. However, it wasn’t until the Pharmacy Act of 1868 that any laws were introduced.

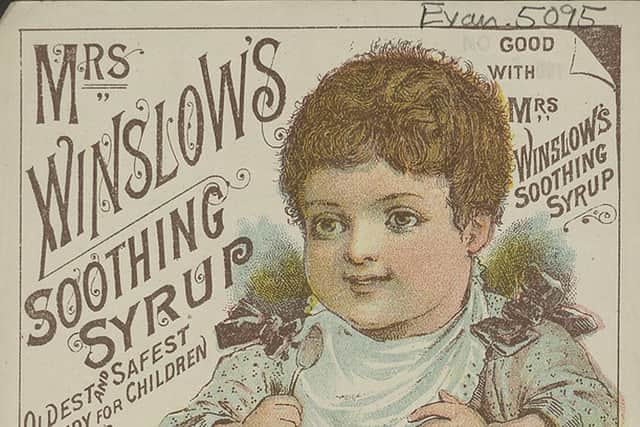

By then, opium was classed as dangerous and sales were restricted, but the Act neglected to include any patented tinctures which included opium as an ingredient, so opium was still widely available. Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, for example, was still used to soothe teething pains in children in the UK until the end of the 19th century.

Opium continued to be sold over the counter until the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920, and laudanum was a vital part of any home medical kit well into the 20th century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA message from the Editor:Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director