Searching for the past at Scotland's last industrial 'ghost town'

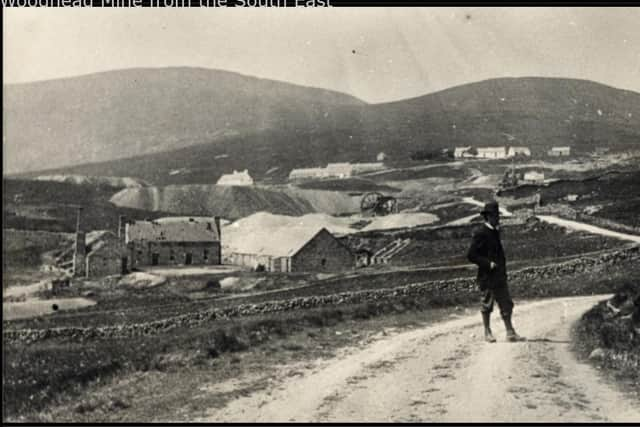

Woodhead was once home to 300 people, but today only a few crumbling remains of the village and the surrounding lead mining operation where they made their living can be seen.

The workers village, near Carsphairn, was built around 1840 by landowner Colonel McAdam Cathcart, who was keen to improve the ‘moral culture’ of his tenants, with he and his wife building a school and donating 1,000 library books to the miners and their families.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow the story of Woodhead and its people is set to be brought to life by archaeologists and local historian Anna Campbell at the site next week.

Ms Campbell said: “I can understand why the word ghost town is used to describe Woodhead. It is a very desolate place, surrounded by hills. You have a feeling that you are in quite an isolated place and yes, it is quite mysterious. There is no explanation of what the buildings are or what they were used for.”

Colonel Cathcart built one of two entire lead production units in Scotland at Woodhead, where the whole process – from the mining, to the washing and smelting – was carried out.

Ms Campbell added: “The village was built on bare rock on the hillside. The houses had slated roofs, which was quite unusual for the time. He had the chimneys built so that the fumes were taken away from where the houses were built. I think it was a well-functioning community.”

A newspaper report from 1844 details a meeting in the new schoolroom, which miners attended in large numbers to “give thanks to Colonel Cathcart for his kindness and liberality towards the workmen under him”.

"Miner John Paterson thanked the Colonel and his lady for their efforts to promote the moral culture of the workmen and their families by presenting to their library … a large assortment of excellent works in every department of literature,” the article said.

The school offered education at a “trifling expense”, with workers paying 1 per cent of their salaries towards their children’s learning. A male and female teacher were appointed on “liberal fixed salaries”.

Ms Campbell said: "The residents took the opportunity to better their lives in a very dangerous environment.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite the huge investment, the enterprise was relatively short-lived. In 1852, the price of lead slumped and production plummeted, with some miners moving to new jobs locally and others heading to the gold mines of Pennsylvania and Australia, Ms Campbell said.

The population plummeted from a high of 301 in 1851 to just 88 a decade later, with production ceasing in 1873. The village, however, clung on and provided housing for self-employed workers in the area, with the last resident leaving in the mid-1950s.

Ms Campbell and archaeologists from Rathmell Archaeology will visit the site on July 13 and 14 for the Can You Dig It community archaeology project, run by the Galloway Glens Landscape Partnership.

Archaeologist Claire Williamson said most of the site was in a very ruinous state, with a building survey to be carried out before further deterioration sets in.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.