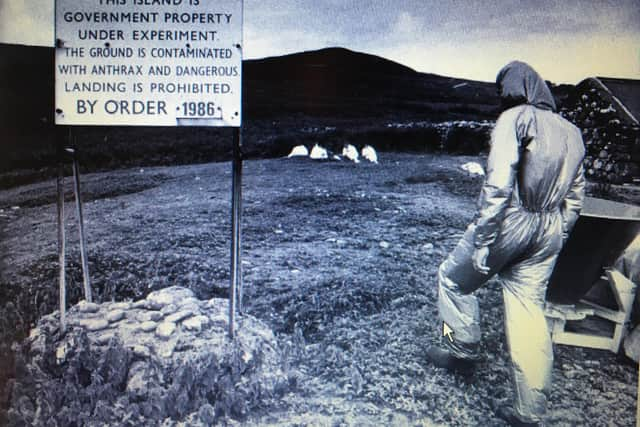

The Scottish islands used as testing grounds

Gruinard, which sits off the mainland between Achiltibuie and Laide in Wester Ross, has effectively been a no go zone for almost 80 years after it became a top-secret UK government test centre for biological weapons during World War Two.

Over the summer of 1942 and 1943, sheep were placed in open pens and then exposed to bombs, dropped from a Vickers Wellington bomber plane, that scattered anthrax spores across the land.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe power of anthrax became quickly clear when the sheep started dying after three days with its potential to cause mass destruction summed up in the report of the tests.

“The report of the Gruinard experiment indicated that biological weapons are highly effective and can paralyse or render cities inhospitable,” said Sharad S Chauhan, author of Biological Weapons.

The island became known as the Island of Death and today few visitors make their way to Gruinard, apart from the odd fisherman collecting a stranded buoy or a curious kayaker lapping at its shores.

As the UK’s interest in biological warfare peaked amid the Cold War,the UK government launched a series of secret trials off the Isle of Lewis in 1952.

A ship, a survey boat and a pontoon were anchored in a bay in the Tolsta district, around 20 miles north of Stornoway, with scientists from Porton Down and the Royal Navy deployed to release a number of biological agent “bombs”, some which contained the bubonic plague, into the air.

Around 2,400 guinea pigs and 100 monkeys were held on board the ship and then taken to the pontoon, where they were strapped in boxes and exposed to the agents released into the atmosphere.

The animals were then taken back to the laboratory on the ship for assessment or post mortem, with those who died later burned. The experiments were later judged to be a failure given the ineffectiveness of the agents in causing harm.

A major panic, however, erupted in government and naval offices after a Lancashire-based trawler sailed through one of the bacterial clouds towards the end of the experiments, which ran from May to December that year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to accounts, the crew went back to shore as normal but were put under government surveillance for two weeks. None of the seamen fell ill with the crew unaware of what had happened until they were approached by a BBC crew decades later.

Islanders remember the arrival of Operation Cauldron, with MPs for the Western Isles later seeking assurances in the House of Commons about the experiments.

Calls for a public inquiry were turned down by Defence Secretary Malcolm Rifkind in 1994.

The only real breakthrough came when the Ministry of Defence was ordered by the Information Commissioner to release a 48-minute film made at the time of Operation Cauldron.

The abandoned island of Roan off the coast of Sutherland was taken over by medical researchers working to find a cure for the common cold.

In 1950, the island was selected for the experiment given the deserted environment offered ideal conditions to build up immunity from infection before being exposed to ‘super spreaders’ who arrived on the island 10 weeks into the test.

Selected for the experiment on Roan, which lost its last permanent resident in 1938, were seven students from Aberdeen University, one from St Andrews, another from London University and a student of forestry.

Their quarantine was broken by the arrival of six students from Aberdeen who had been infected with the common cold in a lab at the university.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA newspaper report said: “For two days their aim was to cough and sneeze everywhere possible, while carrying out three experiments.”

But, according to reports, no one caught a cold. The experiment was saved when a poorly crofter from the mainland was sent to the island to sit for several hours with the students and the couple employed to chaperone them.

By the time they left the island, three of them had cold symptoms. The experiment, led by Harvard Hospital at Salisbury, may not have made a breakthrough on Roan but the team became known for being able to create the common cold in their Salisbury lab, which fuelled waves of further research around the world.

Several hundred years earlier, the Inchkeith in the Firth of Forth was the scene of an experiment ordered by James IV, who wanted to find out the true language of humankind.

In 1493, it is said that two children and a deaf and mute nanny were dispatched to the island with the King wanting to know if a child who was not taught a single word would use the holy language of God instead.

It is not known what happened to the children, but Sir Walter Scott later said he believed the children probably ended up copying the sounds of animals and the natural environment.

Three years later and Inchkeith, along with neighbouring Inchgarvie, was used as a refuge for Edinburgh people

with syphilis. The islands were made places of “compulsory retirement” with sufferers boarding a ship at Leith and ordered to stay there “till God provide for their health”. Most of them likely died.

In the late 16th Century, the island was used to quarantine the passengers of a plague ridden ship with more victims of the disease being sent from the mainland in 1609.