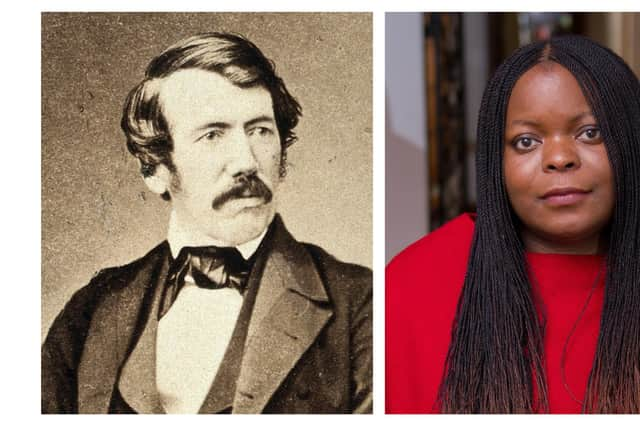

Scots explorer David Livingstone 'decolonised' to reflect Africans who helped build his legacy

It comes as the Livingstone Birthplace Museum in Blantyre, which centres around the small tenement where he lived as a boy and worked at a neighbouring mill, prepares to re-open after a three-year £9m redevelopment.

Petina Gappah, an author and Livingstone scholar from Zimbabwe, has helped to re-interpretate the exhibits and tone of the museum, a shrine to the man who rose through poverty to embark on a 15-year mission to open up the African interior to both Christianity and the outside world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLivingstone, who left for South Africa in 1841, rose to hero status back home as dispatches told of his geographical discoveries, such as the thunderous waters of the Zambezi which he named Victoria Falls after his Queen, fights with lions, clashes with Boers and courageous expeditions through the most dangerous territories in a vain bid to find the source of the Nile.

But those who aided Livingstone, such as interpreters and guides, have gone largely unnoticed with the conflicts in his character also left unspoken.

While an ardent abolitionist who saw commerce and Christianity as powerful tools to end the slave trade, it is known that he bought supplies off East African slave traders as his final, gruelling adventures came to an end.

Ms Gappah first learned of Livingstone as at school in Rhodesia, just before it transitioned to Zimbabwe, where a poem about his achievements was recited by pupils on prize giving day.

She said: “We were told this idea that David Livingston discovered the Victoria Falls, that somehow David Livingstone wrote us into existence.

“He was a white saviour figure, he ended the slave trade in East Africa, he brought Christianity to Africa and also he was a kind doctor who cured the native people of Malaria. It was our own history told in terms of whiteness.

“Later, I studied at a mission school that taught decolonised history.

“We talked about who he met on these journeys, the social conditions of the people, the political organisation of the countries.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Gappah’s latest book, Out of Darkness, Shining Light, tells the story of the 70 men, women and children who walked with Livingstone’s body from what is now Zambia to the coast of Tanzania on a 90-day epic journey following his death in May 1873.

A series of large wooden carved tableux which tell key themes in the Livingstoe story have now been reinterpreted. One, entitled VISION, now suggests Christianity would never have taken root in Africa without Livingstone’s translators and interpreters.

Another, called TRUTH, depicts the banishment of a young woman given her husband could only have one wife. Now, it speaks from her perspective and queries why Livingstone’s truth is more valid than her own society’s beliefs.

.

Ms Gappah added: “The museum is going to be more special. We are going to see the man in proper context. We’re not trying to destroy him or his legacy but we are also talking about the people who mattered in Livingstone’s life.

"We now have a museum that tells of a significant moment in the history of both Europe and Africa. It’s not told from a European perspective or an African perspective, but both.”