The 'Scotophobia' that brewed in London as thousands headed south

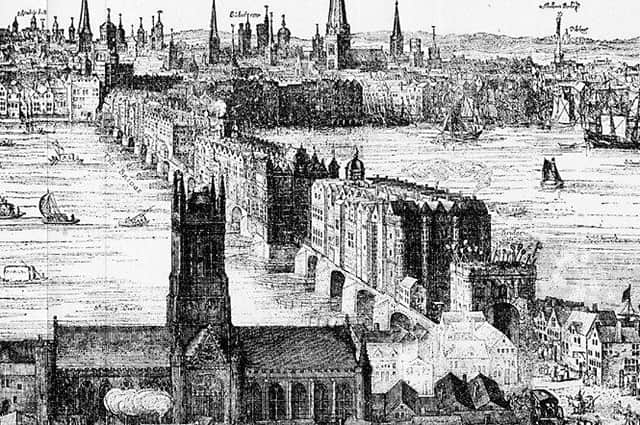

Now, new research has looked at what happened to vast numbers of Scots who were on the move south from the early 17th Century as new opportunities were sought.

From paupers to princes, London held an allure and many fared well in the flourisihing metropolis.

But as the new arrivals settled, a new breed of ‘Scotophobia’ took root with sterotypes appearing in the press, on the theatre stage, in poetry and also on the streets.

Dr Allan Kennedy, lecturer in history at the University of Dundee and Professor Keith Brown, of Manchester University, have investigated this movement of people from Scotland from 1603 to the 1760s with it estimated that around 6% of London’s populaton was born in Scotland by the 18th Century.

“London is, particularly in the 18th Century, becoming the metropolis of Europe and the main driver of Scots going there is the economic potential. No matter what your skill set, London is where the opportunities are, much more than in Scottish cities,” Dr Kennedy, who is also consultant editor of History Scotland magazine, said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAround 35,000 Scots were living in London by 1700 with the figure rising to roughly 60,000 by 1750, the research found.

Many examples of a growing mockery of the new Scots in town were discovered, including one account by an anonymous English writer who claimed London was awash with these new immigrants “idly sauntering and lithering about” with Scots depicted as rude, avaricious, poverty stricken and unclean.

Dr Kennedy, in an earlier article for History Scotland magazine, said the view was “typical of a certain style of Jock-bashing popular in the 17th and early 18th Century England”.

He added: “All of these ideas could be distilled into a characterisation of the Scots as a disease or plague ravishing England.”

As London’s appeal neverthless remained firm, the capital became the “most significant city within the Scottish diaspora” with the new incomers taking up a variety roles.

Clusters of Scots could be found in the military, religion and medicine with “privileged cadre” of peers, landowners and politicians following James VI south following the 1603 Union of Crowns.

Meanwhile, English resentment followed the new King and his “generously rewarded” entourage, Dr Kennedy said.

“James VI took with him to his new kingdom a sizeable entourage of Scottish nobles, courtiers and servants who were generously rewarded, providing native resentment at what the English regarded as place-seekers and hangers-on,” he added

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHostility and Scotophobia grew when the new King tried to forge closer links between his English and Scottish kingdoms.

Dr Kennedy said: “Whenever the relatioship between England and Scotland passed through periods of tension, politically inspired, anti-Scottish prejudice intensified.

“This happened during the civil wars of the 1640s and 1650s, the ‘popish plot’ controversy of the late 1670s and early 1680s, the acrimonious opening years of the union debate in the early 18th Century, the various Jacobite risings and the unpopular ministry of the Scottish nobleman, John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, who served as George IIIs prime minister in 1762-63,” he added.

Visual sterotypes also grew popular in order to distinguish Scots from English, with full Highland dress used as a standard representation. Scots were sometimes shown as visibly unclean or malnourished.

A poem by Charles Churchill, A Scots Pastoral (1763) carried a “horrifying and widely recycled” image of a skeltal, starving Scotsman. Sometimes thistles were used, with one satirical pamphlet showing them bowed before an English peer, who was depicted as a sunflower.

He added: “Taken together, these repeating tropes ensured that, by the end of our period, English printers and pamphleteers had crafted a powerful and instantly recognisable iconography for othering and denigrating Scots.”

The early Scots settlers appeared to favour certain parts of London, such as The Strand and St Martin in the Fields. As numbers grew, so did organisatios to support them with The Royal Scottish Corporation, given a royal charter in 1665.

With Scots in the capital not entitled to Parish relief if they fell ill, were orphaned, disabled or became frail and infirm, the organisation was set up to help those fellow Scots who had fallen on hard times. The organisaiton still exists today under the name ScotsCare.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“While many of the Scots migrating to early modern England were able to exploit economic opportunities, there were others whom life turned out to be uncomfortably challenging. Some simply failed to make a go of things and ended up returning home,” Dr Kennedy said.

Some ended up as vagrants and beggars, and were punished accordingly - usually by whipping – before being sent north.

Dr Kennedy said that despite the emerging Scotophobia, the Scots emigrants generally did well in London and did not encouter racism. Work was they key to Scots finding their rightful place in the city.

“There is little evidence to suggest that the well-estabished discourse of Enlgish Scotophobia filtered down to impact significantly on the every day lives of ordinary Scots migrants. Assimilation contiued and Scots ‘ghettos’ did not appear.

“Scottish migrants were well-placed to embed themselves in English society. The most obvious route into the local community was finding work and Scots did that remarkably well.

“Unlike many other migrant groups, such as the French Huguenot, Saphardic Jews or the Irish, they did not tend to find themselves restricted to particular ‘Scottish’ specialisms.

“Rather, they could be found operting at virtually all levels of the English economy, from kingship to pauperism.”

Further research by Dr Kennedy found that Highlanders heading to London did not appear to face a specific form of prejudice, perhaps given that most left areas where English was broadly spoken, such as Perthshire and Inverness.