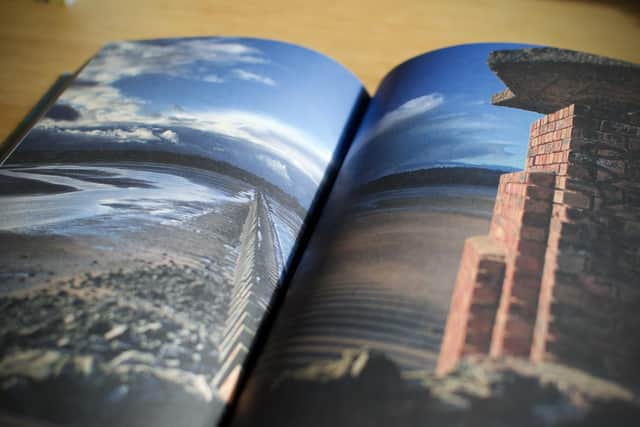

Scotland's 'lost and overlooked' historic sites and 'wild history' explored in new book

They are the “lost and overlooked”, the historic sites of Scotland that fade quietly into the landscape as time wears on.

Left broadly untouched by humans and now in the hands of nature’s fate, they sit far off the map of Scotland’s big tourist draws and the rumble of tour buses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow writer James Crawford has ventured deep into Scotland to search for the fragile places that tell the country’s long story and of evolving landscapes that once heaved with human activity for his new book Wild History: Journeys into Lost Scotland.

He has reached places once central to ritual, shelter, work and war, but whose presence is now often faint and disappearing, now the people have gone.

From a pagan site of worship to a “ghost town” village that vanished completely in the 20th century, thousands of years of past lives are crossed here. Places of Vikings and Picts are encountered, as are the forgotten roads and routes that once connected people.

Often on foot, sometimes by boat and frequently in the pouring rain, Crawford moves along rivers, through mountain passes and across moorland to these places which exist off today's beaten track. The starting point, for all 55 of these journeys, is a reference point on an Ordnance Survey map.

Getting there, Crawford says, is part of the process for reaching a closer connection to history, its places and its people outwith the ticket offices and interpretation boards of the most visited and conserved landmarks. This, he says, is history “unfiltered”.

“This book is about those places that were once occupied and now are not,” he says. “The ones that are largely forgotten and largely unvisited. Of around 25 per cent of the places that I went to in writing this book, I didn’t see another person there.”

In writing this book, Crawford had found – and hopes to share – a “more intimate, enriching” way of engaging with the past.

He says: “It is in part of having worked in the heritage industry for ten years, to some extent you come very aware of how much it is an industry. In being an industry, a lot of it becomes about filtering people to the mega sites and, of course, there is a reason for that and why these sites receive so many visitors.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But at the same time, I feel there can be a lack of imagination in how we can engage in our history. I find myself having a much more intimate connection to the past by going to these sites that are very much off the beaten track. They are unfiltered, they are un-curated.”

Wild History, which follows his successful Scotland from the Sky book and television series, was partly inspired by his time working in the archive for the Royal Commission for Ancient and Historical Monuments and Construction, originally set up in 1908 to record buildings which reflected Scotland’s culture and civilisation up until 1707.

Secretary Alexander Ormiston Curle oversaw a vast expansion of its remit and set about personally inspecting monuments and sites, heading out on his bicycle and on foot with his map and later writing of the “intense pleasure” found in these journeys.

Crawford, in his search for the 17th-century Fasagh ironworks at Loch Maree, endured torrential rain, boots filled with water, thick bracken and a two-hour walk to find the last remains of the industrial site and its ‘Sassenach Graveyard’ for workers.

Later, bright July sun broke through on his sodden walk to Peanmeanach on the tip of the Ardnish peninsula, where people settled from at least the Iron Age through the Norse period and right up to 1941, when the last person left.

He says: “There is very much a sense that you cross the West Highland Line on to the Ardnish peninsula and it is very much like stepping through a portal. It’s not that cliche of stepping back in time, it is this awareness that you are crossing into a space that is set adrift from time."

As abandoned Peanmeanach appeared before him, smoke rose out of one of the chimneys of the old cottages, which is now used as a bothy.

“There was something really beautiful that I had come to a place that has been abandoned, but there was this transitory life there,” Crawford says. The family offered me a cup of tea.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt Inchkeith island, where once 1,000 soldiers defended the Firth of Forth, he found an almost “post human” landscape that had been reclaimed.

“It’s basically now a seagull colony and actually as a human, it’s a hostile environment,” he says. “That was one of the wildest places I went to because it was the harder side of nature.

"That felt incredibly post human. Life was abundant and thriving, but we were not welcome there. You got a feel for what would happen if humans didn’t exist any more, if humans were gone.”

If he could recommend one place in the book to visit, it would be the sacred site of Tigh na Cailleach in Glen Lyon, a shrine to the goddess of winter that is still maintained by gamekeepers who work this land where the Cailleach – or old woman in Gaelic – is believed to have once lived.

Once considered a giantess of creation, she became known as a nature spirit who could lead deer herds safely through winter or bestow bad luck on a hunter – or even lead him to the underworld. But the Cailleach, with grey hair and eerie blue skin, could also bring mild winters and lead animals and crops to thrive.

Today, a little thatched house can still be found in the glen with four stones, which represent the Cailleach and her family, sitting outside.

Crawford writes: "Every May Day, according to that old tradition, the statues are taken out of the house and placed facing down the glen. And every Halloween, they are returned inside, to wait out the winter.”

This is history unfiltered, history as is – and history still very much alive.

- Wild History Journeys into Lost Scotland, by James Crawford is out now and published by Birlinn

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.