Remembering Scotland’s 'working class martyrs' who were hanged 200 years ago this week

Andrew Hardie and John Baird walked towards the “dreadful apparatus” of their execution 200 years ago this week with composure, according to accounts. Waiting there was the

headsman, a man of around 18, who was dressed in a black cape and fuzzy hat, who was recognised by some in the crowd following the execution of their friend, James Wilson, n Glasgow the week before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The decapitator, clad in a dark cloak and veiled with black crepe, held up his weighty axe in the same appalling manner in which he held it at Glasgow,” one account said.“Both the prisoners, but especially Hardie, looked eagerly and keenly at their veiled companion, but did not address him,” it added.

As Hardie, 28, and Baird, 32, took their final position, between 2,000 and 6,000 members of the public looked on, as the execution of the men charged with high treason and sedition following Scotland’s short-lived Radical War drew near.

The insurrection was built in the aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre, where hundreds were injured and 17 killed near Manchester as thousands gathered to call for reforms to the electoral system.

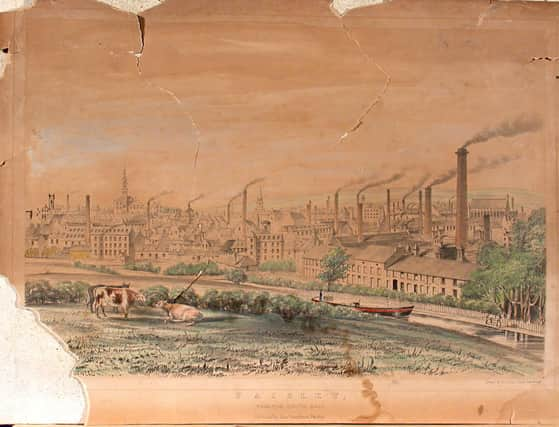

As dissent filtered through Scotland, demands for universal male suffrage, better working conditions and a Scottish parliament intensified with the action led by a group of educated skilled artisans, such as handloom weavers and shoemakers, with towns such as Paisley at the nerve centre of the unrest.

Among them were Hardie, from Glasgow and Baird, from Condorrat in North Lanarkshire. Both had military experience, with Baird recruited as a trainer for the planned armed insurrection. Weapons such as pikes and wasps –a type of javelin – were made after dark in towns and villages across the Central Belt.

Hardie was linked to the Proclamation, written By order of the Committee of Organisation for forming a Provisional Government, which called for a mass strike of skilled workers in early April 1820. Around 60,000 people heeded the call.

Both were arrested after the Battle of Bonnymuir in early April 1820, where around 30 radicals marched to the Carron Iron Works at Falkirk to steal cannons but were seized by troops on the way.

In a letter written in Stirling Castle to his uncle three days before his death, Hardie showed little contrition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe wrote: “No person could have induced me to take up arms in the same manner to rob or plunder. No, my dear friends, I took them for the good of my suffering country; and although we were outwitted, yet I protest, as a dying man, that it was with a good intention on my part.”

As Baird and Hardie stood in front of the gathered crowd on 8 September, 1820, around an hour was spent psalm singing. Each were offered a glass of wine, before being taken to the scaffold which was “prepared with all the insignia of death”.

An account added: “The prisoners then went on the platform at a quarter before three o’clock. On their appearance the crowd set up a faint cheer.”

Addressing the crowd, Hardie advised his “countrymen” not to go to the pub but instead read the Bible. The ropes were then adjusted, a prayer read and the pair “launched to eternity” at eleven minutes before three.

An account said: “After hanging half an hour, they were cut down, and placed upon the coffins, with, their necks upon a block; the headsman then came forward.“On his appearance there was a cry of murder.

“He struck the neck of Hardie thrice before it was severed; then held it up with both hands, saying, ‘this is the head of a traitor’.”

Baird was given the same treatment.

The coffins were removed and the crowd quietly dispersed, with Hardie and Baird no longer with life but now with the powerful status of martyrs.

Archie Henderson, social history research assistant at Paisley Museum, is working on the Paisley Re-Imagined Project, which is looking at the town’s role in the 1820 Radical War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said in the years that following the exection, the radicals had widespread throughout Scotland’s working classes, with ballads immortalising Hardie and Baird.

Mr Henderson said: “The opinion of the people was that they died as martyrs and there was a feeling that they were executed unfairly. They were martyrs.”

He said the legacy of the radicals lived larged.

“The right to vote we enjoy today was in part paid for with the blood of John Baird and Andrew Hardie, who from the moment of their execution became martyrs to the suffrage movement.

"The fight continued after their deaths and lead towards the Chartist movement, the Reform Act of 1832 and, ultimately, the 1928 Representation of the People Act that gave vote to all men and women on equal terms."

-A podcasts to commemorate 200 years of the Radical War will go live on Paisley.is on Tuesday September 8.

Paisley Museum, which is undergoing a £5million redevelopment, holds a number of objects relating to the Radical War. For more information, visit reimagined.paisleymuseum.org