New Lanark: When the industrial powerhouse became an abandoned ghost town

In its early 19th Century, around 2.500 people called New Lanark home where their employment in the cotton mills also secured them access to decent housing and education for all under the vision of Robert Owen.

Once celebrated across Europe as an industrial utopia where commercial success and engineering innovation met with social reform, the last mill ceased production at New Lanark in 1968 as its then owner, Gourock Ropeworks, struggled to sell the operation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor years, their business floundered with a lack of investment in the housing stock accelerating the decline of the prized New Lanark model.

After Gourock Ropeworks left, a silence fell on the village set on the banks of the fast flowing section of the River Clyde.

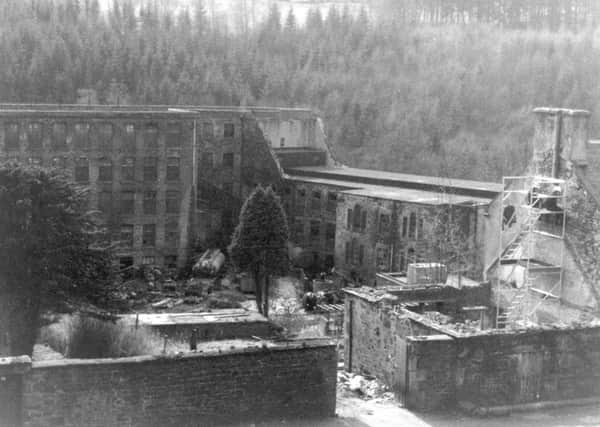

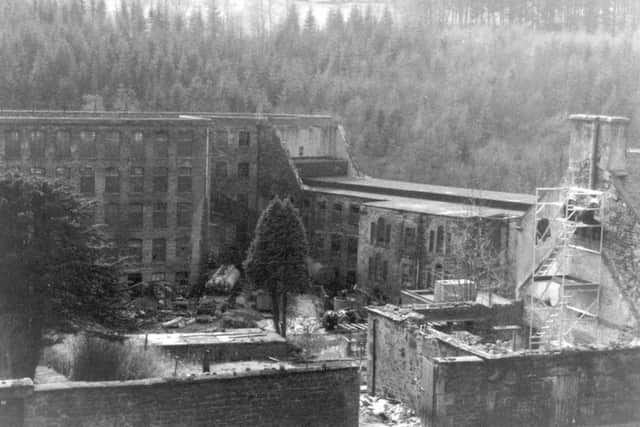

The remaining population sunk to around 12 as a small number of former workers hung on. Meanwhile, the once-mighty mill buildings started to deteriorate with their lack of purpose.

The last resident left in 1974.

Helen Martin, collections officer at New Lanark, said: “People described New Lanark then as becoming like a ghost town. It is really part of the New Lanark story that hasn’t been told.

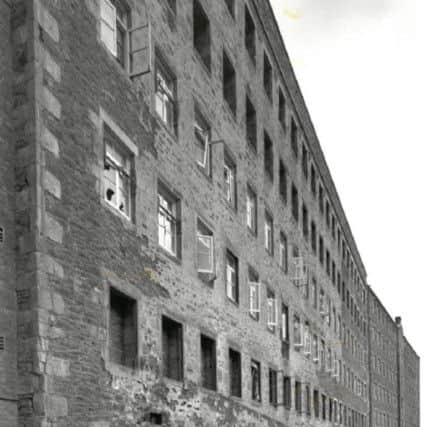

“Many people come to New Lanark and see it as a very well preserved, historic place but people forget that it was for some time in a horrendous condition and how much work was needed to be done.”

As the condition of the site deteriorated under the ownership of Gourock Ropeworks, the New Lanark Association was set up to refurbishing terraces in Caithness Road and Nursery Buildings and converting them into viable modern properties.

In 1974, the precursor to the New Lanark Trust was founded to prevent demolition of the village but the job to restore and conserve the site became a costly challenge as time wore on.

“For some years, as the fabric of other buildings crumbled and no progress was made in combating decay, visitors including many an overseas pilgrim to the birthplace of the co-operative movement rightly had the impression that New Lanark’s physical heritage was seriously at risk,” a report in the Illustrated London News in November 1980 said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA compulsory purchase order was used in 1983 against its then owner, scrap firm Metal Extractions Limited, to recover the mills after a repairs notice was served in 1979.

Following work led by the New Lanark Trust and its wholly owned companies, the mills are now put to various uses.

Mill Number 1 is now the New Lanark Mill Hotel while Mill Number 2 is used as the village heritage centre, complete with working loom, and cafe. The smaller mills are now used as office space.

Around 200 people live in New Lanark today in a mix of privately owned and social housing. Around 400,000 people visit the village, a UNESCO World Heritage site, every year.

A new exhibition will open at New Lanark later this year to tell the story of the remarkable model village through the ages.

It is being mounted in collaboration with Historic Environment Scotland as part of its “Industry and Aesthetics” exhibition which explores emotional responses to photographs of abandoned industrial spaces.