Insight: Saving the broken heart of Glasgow - Dani Garavelli

It’s disconcerting to stand behind the fence, with its "Keep Out" sign, and take in the eerie silence. I used to live around the corner. Every day, twice a day, for years I would walk past en route to my own children’s primary, across the road and up the hill. I would hear the bell ring, the stampede of feet, laughter in the playground.

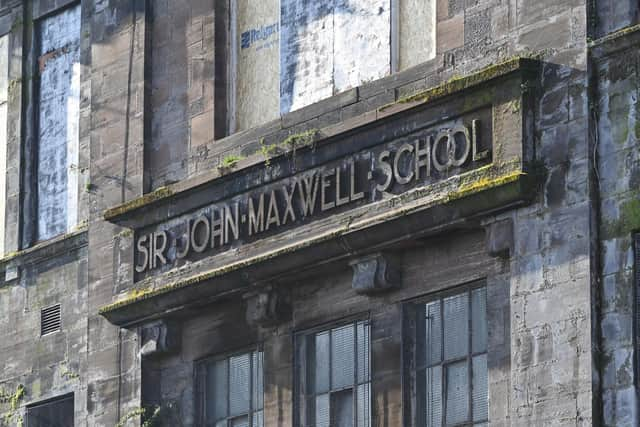

The area has been transformed since I moved away in 2007. The A-listed Pollokshaws Burgh Hall still stands to the right of the school, in a blaze of cherry blossom. But the high rises to its left have been pulled down and replaced by brutalist low-rises. As the population declined, so too did the school roll, until it became obsolete. It closed in 2011 and has been deteriorating ever since.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Sir John Maxwell School is part of Glasgow's threatened heritage. Hundreds of architecturally important buildings have been lost since the 60s; and many more are imperilled. There are currently 117 city buildings on the at-risk register; some have languished there for several decades, suspended between demolition and abortive plans for regeneration.

They are a victim of history, of industrial decline, of the pursuit of urban Utopias which turned sour. They are a victim of the present too: of austerity, demographics, neglectful owners, and - some would claim - a lack of civic vision. Like Detroit - once a centre of car manufacturing - Glasgow is a former million city. Its population declined from a peak of 1.1m to 520,000 at the turn of this century, though it has risen to 600,000 since. Part of that decline was caused by policies such as the slum clearances which saw the “cream” of its citizens decanted to new towns such as East Kilbride.

Now Glasgow is - to borrow an analogy - a fat person, who has shed lots of weight, swamped by her oversized clothes. While the city is not as dysfunctional as Detroit - with its desolate ghost estates - it has patches of blight. Since fire took out the Glasgow School of Art and the ABC, the top of Sauchiehall Street has become a wasteland. “And then there’s Possilpark,” says Labour MSP Paul Sweeney. “Saracen Street is such a proud street, but look either side of it and there’s nothing left. If you want the Detroit vibe, that’s where you would go.”

Sweeney is standing with me outside Sir John Maxwell School. “This was once an ancient village ” he says about Pollokshaws. “It fitted together in an organic way. But in the 60s and 70s, the heart was torn out of Glasgow. Communities were scattered to the wind, and all those soft connections and networks you need for a functioning society were fragmented. That’s how you get a situation like this where a school is suddenly redundant.”

He and Niall Murphy, deputy director of Glasgow City Heritage Trust (GCHT), have agreed to take me on a tour of some of the buildings which have fallen prey to these socio-economic factors. Like many people, I became more engaged with the city’s architectural legacy over lockdown. I am hoping they will help me understand the factors that have left the future of so many of our great edifices in doubt and what, if anything, can be done to save them.

Sir John Maxwell School is owned by Glasgow City Council and, unlike most of the buildings we will visit, is not listed, which means it is not eligible for grant funding from the GCHT or similar bodies.

Some of those who have witnessed its deterioration would rather see it gone. But Murphy says it is still of architectural and historical value. Designed by Alexander Hamilton who trained under John Archibald Campbell, one of the first Scots to study at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, it’s an unusual mix between two architectural schools: Glasgow Baroque and the Glasgow Style. Hamilton had a promising career ahead of him, but signed up in WWI, turning down the role of officer to serve with rank and file soldiers, and was killed on the first day of the Somme.

The former primary has other stories to tell, too. Red Clydesider John Maclean taught there, and it was the first Scottish school to have a Gaelic unit, and so was at the forefront of the debate over the importance of preserving the language.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Sir John Maxwell School Trust has been formed to save it. The trust has lobbied the council which has stayed demolition and spent £270,000 securing the site. One proposal is to turn it into a £6.3m eco-hub, but given it’s a large building, which will have ongoing maintenance costs. Is that really feasible?

Sweeney concedes such projects are tricky. “It’s easy enough to pull together the capital funding, but how do you make sure it washes its face on an ongoing basis? A lot of quixotic ideas about community-orientated uses for buildings will never be achievable so sometimes you have to weigh it up. Do you want to save it? That might mean selling it to a developer to convert it into apartments.”

Just over a mile away, in Cathcart, is the B-listed former Holmlea School. It lay empty for a decade but has now been converted into 49 affordable flats by Home Group working with the council and Cathcart & District Housing Association. “There are lots of lovely touches,” says Murphy pointing out an old gatepost which carries the words of the children’s poem Ally Bally Bee.

Cathcart is a relatively affluent part of Glasgow. Buildings in deprived areas, with lower land values, are more difficult to repurpose because of the "conservation gap": the difference between how much it will cost to bring an old building back into use, and how much it will be worth when the project is finished.

Yet, the preservation of such buildings is about more than civic flexing; it is tied to a sense of continuity, identity and self-worth. “It’s about knowing where you come from; about your memories of a place," says Murphy. "If a place is destroyed, and you lose your sense of bearing, it can be undermining of you as a person. [Former chief medical officer for Scotland] Sir Harry Burns is adamant it has an impact on your psyche and your health. It’s like what the Nazis did with Warsaw: if you destroy the city, and you destroy the culture, then you destroy the spirit.”

*********

The next stop is the Caledonia Road United Presbyterian Church in what used to be the heart of the Gorbals. Murphy tells us a story. “I took a walking tour round here once,” he says. “There was this old guy with us. He’d been a pupil at Hutcheson’s Boys School and had been looking forward to visiting the area again, but he was completely disoriented. He burst into tears. He said: ‘I don’t recognise this place. Where am I?’”

Several cycles of demolition and regeneration left the man dislocated. Ditto the building. One of only two remaining Alexander Greek Thomson churches in Glasgow, it was once flanked by the southside railway terminus on one side and a row of tenements on the other. Now the campanile-style tower and colonnade stand on a traffic island on a busy intersection. On the tarmac in front, the outline of a recently-demolished tollbooth is marked out like a murder victim’s. So much traffic ploughs either side of the church, we have to raise our voices to be heard. Murphy runs his finger along the side to show me how pollution has reduced some of its stonework to sand.

The church's congregation had already departed by the time arsonists struck in 1965. It would have been demolished had US architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock not written a strongly-worded letter to The Herald insisting it should be saved.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Since then it has been a consolidated ruin; a shell lit up at night like a beacon. Proposals for its use have come and gone. One wild notion was to take it down brick by brick and rebuild it at the top of Buchanan Street. More recently, the Alexander Thomson Society had hoped to turn it into a museum. “Again, it's a nice concept, but how would it have survived?” asks Sweeney. “When you have buildings like the Lighthouse which are already financially stressed, you can’t really load Buckaroo any more.”

Elsewhere, old churches have been turned into pubs/restaurants: Oran Mor and Cottiers in the West End, the Church on the Hill at Langside are thriving. But - with no community and no through-trade - it’s hard to see that happening here. And yet there are exciting things going on nearby. New housing developments are being built in Laurieston; the refurbishment of the Citizens Theatre is well underway, and - after years of lying vacant - the old Linen Bank has been converted into flats.

Sweeney believes that - with a bit of imagination - the Caledonia Road Church could also be transformed. “There are things you could do," he says. "You could calm the traffic to 20 mph, you could take down the fences that run along the side of the road and connect this traffic island back up with the New Gorbals. You could create a beautiful plaza. No publican is going to approach the council while it looks like this. The council needs to get out there and sell a vision of what it could be.”

**************************************

Dressed in aubergine cords and a purple Paisley pattern-style shirt, Murphy would brighten up the drabbest of landscapes. Born in Hong Kong to Scottish parents, his passion for architecture was inspired by the skyscrapers he could see from his home on the Peak, the former colony's most desirable neighbourhood. He loved it there, but had always travelled back and forth to boarding school and then to the Glasgow School of Art. When Hong Kong was handed back to China in 1997, he decided to make Pollokshields his home.

Sweeney, who is also a trustee of GCHT, grew up in the north of Glasgow. His interest in the city’s heritage was sparked by poring over his grandad's books of lost buildings, then trying to recreate them in Lego. They were both radicalised by what they saw as acts of wanton destruction: the demolition of the A-listed former Elgin Congregational Church in Pitt Street (Murphy) and the demolition of the Springburn Public Halls (Sweeney).

The tearing down of the church (by then the Shak nightclub) in 2004 came after a blaze ripped through the building. “The portico was the one thing that hadn’t been touched," says Murphy. "It was intact and then the bulldozer went through it. There was no transparency at all about who was making decisions.”

Springburn Halls met the same fate in 2012. Sweeney saw it as a slap in the face for an already demoralised community. Now the pair have joined forces to defend the city’s architecture. This feature was triggered by Sweeney’s dismay over the decision to demolish the former Robinson & Dunn Temple Sawmill in Anniesland (later the Canal Bar) - one of Glasgow’s few art deco buildings - to make way for a housing development. What angers him, he says, is that the Sawmill had been deteriorating since 2004 when the Canal Bar lost its late licence; but now the owner Stefan King is going to profit from its destruction.

He and Murphy take me to other at-risk buildings in private ownership. There’s the Govanhill Picture House, with its exotic Egyptian facade; the art deco Leyland building - a sleek slice of Florida in the heart of Tradeston; and the distinctive A-listed Lion Chambers, made of reinforced concrete, in the city centre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike ageing film stars, these buildings retain a faded glory. The Govanhill Picture House harks back to the city’s days as a Mecca for cinema-goers (though many of those cinemas later became Meccas). The columns at the entrance are freshly-enough painted, and the ornamental motif of a double-headed creature above is intact, but the shops on either side have lurid signage and roller shutters. “They are not in keeping with the rest of the building and will be in breach of the planning consent,” Murphy tells me. Later, the council confirms it is the subject of an ongoing planning enforcement investigation. Recently, the GCHT has been working with the Glasgow Artists' Moving Image Studios in the hopes the upper storey could be turned back into a cinema showing art house films.

The Leyland building - my personal favourite - still has its fluted pilasters and its iron balconies. You can picture it lit up with neon on Miami Beach. But its lovely curved windows are boarded up, and the only colour comes from the graffiti daubed on its walls. Once used to house police horses and dogs, there are now garages round the back, but the space at the front is empty and deteriorating. A planning application has been submitted to turn it into kitchens for an Uber Eats-style business. Sweeney makes a mental note to write to the planning department asking that restoration of the facade be a condition of consent.

But the building the GCHT receives the most calls about is the beautiful Lion Chambers which towers over Hope Street. Built in 1907 using the experimental (and flawed) Hennebique System, it once housed a mix of lawyers and artists. Two legal luminaries - Sheriff William Guthrie and Lord Scott Dickson - still cast their stoney gaze from behind the mesh frame put up to protect passers-by from falling masonry, but the upper storeys have been empty since the 1990s, the ground floor and basement since 2009.

“I was inside three years ago,” Murphy says. “That summer, thieves had got in and stripped the lead off the dome. It’s full of pigeons now; guano central.”

According to the GCHT’s snapshot report for 2019, 50 per cent of “at-risk” buildings in Glasgow have been on the register for 11 years, and one in four have been there for 15 years. And - though, since 1990, 2.7 Glasgow buildings have been saved for every one lost to demolition - there is a steady flow of buildings falling into a state of disrepair. “It’s a constant war of attrition,” Sweeney says.

So why isn’t the council doing more? As always, much of it comes down to resources. All local authorities have seen their income fall, with a lot of what they do receive ring-fenced. Glasgow's shrinking population has left it with lower council tax revenue. But is there a lack of ambition, too?

Norry Wilson runs the heritage website Lost Glasgow which documents the city’s faded grandeur and has 350,000 followers. “You go back to the building of the Burrell, the Garden Festival, the City of Culture - the council did have a bold vision for what Glasgow could be. That has dissipated,” he says. “Huge chunks of it seem to be in managed decline.”

Local authorities have powers they can use against irresponsible or neglectful owners, yet these are not always invoked.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Both the current [SNP] administration and previous Labour administrations have been bad at enforcement,” Wilson says. “If you or I let our private house go to rack and ruin, our neighbours would complain and we would come home to a maintenance order telling us to fix our roof. And yet businesses are allowed to ‘landbank’. London-based property investment companies, with no stake in Glasgow, and other owners buy up entire city centre blocks and do no maintenance until the existing businesses move out. Then the building starts to fall down and the owners say it’s too expensive to repair and we will just have to demolish and build something else."

Yet Wilson has some sympathy for the local authority. “Glasgow City Council is skint,” he says. “If it comes up against a multi-million pound development company, the multi-million pound development company employs its own planners and designers and writes a 150-page report saying why this building must be demolished. The small team of council architects have neither the time nor the money to go out and rebut every point.”

*****************

Of course, there is no point in the council using enforcement powers unless it plans to follow through and apply the penalty for refusing to comply. In many cases, that penalty would be a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO), but the council is reluctant to use a CPO unless a back-to-back deal is in place; if not, it will be left with yet another derelict building to add to its collection.

As part of their tour, Sweeney and Murphy take me to the Beco building in Tradeston. Fifteen years ago, this former warehouse with its regimented rows of rectangular and arch-shaped windows was the subject of an inter-Labour rammy between then council leader Steven Purcell, who wanted it demolished, and Culture Secretary Patrica Ferguson, who wanted it saved.

Today it is being given a new lease of life, thanks to a back-to-back CPO. Last year, the council forced its multiple owners to sell before “flipping” it to Barclays which is turning it into an “innovation hub” for public use as part of its massive investment on the south bank of the Clyde.

The clanking of construction work and the smell wafting from nearby food outlets suggest the area is on the up. Sweeney hopes the Barclays campus will increase land values in the area, promoting a wave of regeneration which could wash back as far as the Leyland building.

“This gives you an insight as to what the council could do if they were a bit more dynamic,” Sweeney says. “Rather than waiting for a big blue chip to come in and give them security, why couldn’t they do it more often with community groups and housing associations? Why is the threshold so high?”

******************

Our last stop is the Springburn Winter Gardens. This hulking steel frame is close to Sweeney’s heart. The son of a shipbuilder, he grew up nearby; as a child he would wander the ruin imagining it was the wreck of the Hindenburg. Later, he used to fantasise about the Springburn Public Halls being restored to their former glory. Like other activists who had campaigned for their preservation, he channelled his anger over their demolition into making sure the glasshouse didn’t suffer the same fate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough I had seen pictures, nothing prepared me for the sheer scale of the structure, its giant arcs now russet with rust under a canopy of blue sky, and a bracket dangling precariously in space.

“It was built by the Reid family in 1900,” Sweeney tells me. “They were world leaders in building steam engines. They felt they had been involved in ‘despoiling the sylvan beauty and rural charm of Springburn’ and wanted to give something back. And so the Winter Gardens became a showcase for the area’s industrial prowess, but also an exotic fantasy world in the middle of this sooty city.

“It was all fine until 1983, when a huge storm blew out a section of the glazing. When they went in to inspect it they realised the astrigals which held it in place were badly rotted. At that time the city was quite distressed financially, so it was left to fall apart.”

During the 80s and 90s, there were several abortive restoration plans, including moving it to the Garden Festival site, before local activists formed the Springburn Winter Gardens Trust in 2013.

So far, they have raised £250,000. The funds have been used to clear away trees, stabilise brickwork and repair the clerestory and thistle brattishing which was bowing as the surrounding steelwork corroded. Some of that metal now lies at our feet. Sweeney points to a beam with the words “Glengarnock steel” emblazoned on it. “That’s steel from the Ayrshire company that supplied it to the Titanic,” he says.

We sit underneath the former glasshouse - like the upturned hull of a sunken liner - as Sweeney conjures up a vision of its future.

It would cost £1.5m just to keep it as a stabilised ruin, £10m to restore it and turn it into an entertainment venue, similar to the Kelvingrove Bandstand, but with new-build catering and childcare facilities tagged on. That may seem a lot, but Sweeney hopes the project will be selected in the next phase of the levelling-up fund and has been buoyed by the Pollok Country Park Stables and Sawmill project’s £13m award.

“When you have a ruin like this in the middle of one of the poorest districts of Glasgow, it sends a signal that the community is not valued; that it has seen better days,” Sweeney says. “I think rebuilding it would make a statement that Springburn is back on the scene.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe tour over, Sweeney hands me a book to borrow: Frank Wordsall’s The City That Disappeared. Together, we leaf through its pages, gazing at all the great lost masterpieces of Glasgow; the grotesque acts of vandalism perpetuated in the name of modernisation. And I wonder how many of the buildings I’ve seen today will still be standing in 10 years’ time.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.