Insight: How the Declaration of Arbroath became an article of political faith

As Robert the Bruce and his trusted circle of advisers and supporters gathered at short notice near Edinburgh 700 years ago, there was everything to lose.

While by now almost an unbreakable military force, Robert I was fighting to hold on to his ever fragile grasp on legitimate power.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe exchanges between the king and the papacy were increasingly disastrous, so much so that an order was made for curses to be said against Bruce and his key men in English churches three times a day .

A credible threat to his place on the throne was also now emerging. The pressure was on Bruce as he arrived at Newbattle Abbey for the general council meeting in March 1320 with his closest allies Sir James Douglas – the Black Douglas – and Thomas Randolph, the 1st Earl of Moray, almost certainly by his side as business got under way.

It was a “serious gathering with a serious purpose”, according to Professor Dauvit Broun of Glasgow University.

What resulted from that meeting was an electrifying political document, the Declaration of Arbroath, which celebrates its 700th anniversary this year.

The letter to Pope John XXII recognised Scotland’s right to assert itself as an independent nation. Crucially, it extends the community of the realm beyond the king and nobles to the people themselves.

They had the right to choose the king and depose him if he subjected the kingdom to English rule.

The mighty declaration, which has gone on to influence other key political documents including the American Declaration of Independence, also served a more immediate purpose for Bruce and his men back in 1320.

It was written to protect the power of Bruce and his noble supporters as their positions became ever more precarious, it has been argued.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProfessor Broun said: “At the time of Newbattle, there were two things going on. The first was that there was no adult heir because Bruce’s family had been decimated.

“His brother, Edward, had died in Ireland in October 1318 and his daughter died shortly after childbirth, so if he were trying to establish a dynasty, it is not looking good.

“His lack of blood heir makes him very vulnerable.

“The second thing, that makes him even more vulnerable is the emergence of Edward Balliol. He is an adult and his father, John, was king by due process.”

At the time, Bruce’s party was under “intense international pressure” from the Pope to end the war between England and Scotland.

“He is forcing Bruce into a corner and by that time he was facing UN-style sanctions. Bruce and his men have got to do something and that is the origin of the Declaration of Arbroath,” Professor Broun said.

Crucially, in an assertion of Scotland’s right to be recognised as an independent kingdom, the document mapped out the root of the Scottish people who forever through time had their own kings that descended from Scota, the daughter of an Egyptian pharaoh.

In a further assertion of Scotland’s independent status and the authority of its people, its most famous passage reads: “As long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule.

“It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours, that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe letter to the Pope also set out the position that if Bruce failed to protect the kingdom of Scotland from English rule, the people would have a right to depose him and choose their own monarch to defend them.

In light of this, the deposition clause could be read as being written in “anticipation of the plight of the Bruce party” if he lost the crown, Professor Broun added.

“It is not just Bruce, it is of course all the others around him who stood greatly to lose,” he said.

Religious wrath, duplicity and ongoing violence paved the road to Newbattle.

In June 1318, following Bruce’s raids into Northumberland and Yorkshire, when castles were seized, cattle stolen and hostages taken, the Archbishop of York, with the backing of the Pope, published a sentence of ex-communication not only against Bruce but his accomplices, with all of Scotland placed under an interdict.

Three months later, divine vengeance was ordered with services to be held three times a day across England with curses said against Bruce, Douglas and Randolph.

A truce, however, seemed possible and Edward II opened negotiations in Berwick in December 1319, with peace to fall from the next month. It was not to last, with the English king quickly reneging and lobbying the Pope to renew pressure on the Scots,

What followed, was a papal bull of “unprecedented rancour “ with Bruce summoned to Avignon, but the king refused to receive the letter given it was addressed to Robert the Bruce, Governing the Kingdom of Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe offence was deep, not least as an earlier communication – also refused – was addressed to Robert the Bruce – Acting as King of Scots.

Bruce’s rejection of the meeting infuriated the Pope with the Archbishop of York and the bishops of London and Carlisle told to repeat the excommunication of Bruce every Sunday and feast day. The bishops of Moray, St Andrews, Dunkeld and Aberdeen later followed the interdict.

It was enough to drive Bruce and his men to meet at Newbattle.

“The papal invective at last provoked noble remonstrance from the Scottish nation,” wrote Ronald McNair Scott in Robert The Bruce, King of Scots.

After the general council, the letter to the Pope was finalised over the coming weeks, most likely by Bernard, Abbot of Arbroath and Chancellor of Scotland, although it is not absolutely certain that it was written in his Angus abbey.

The declaration was supported by a mix of Bruce loyalists and others who fought against him at Bannockburn, such as Sir Ingram de Umfraville, who switched sides between the English and the Scottish several times during the Wars of Independence.

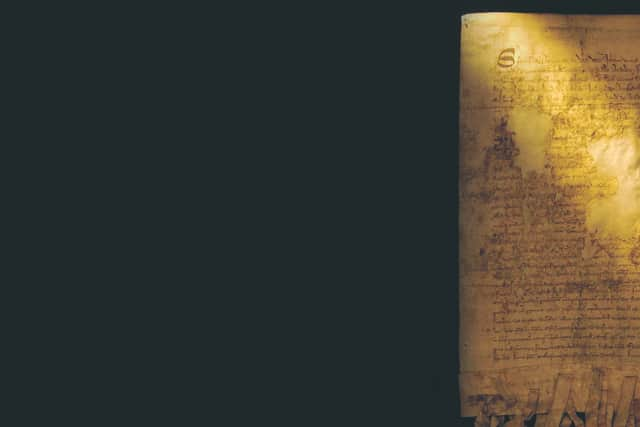

Written in Latin, it was authenticated by the wax seals of eight earls and around 40 barons, of which just 19 now survive on the “file copy” of the declaration, the only version to survive in its original form.

Known as Tyn, the version is named after Tyninghame, the East Lothian estate of Sir Thomas Hamilton of Byres, later the 1st Earl of Haddington, the former Clark Register, or keeper of the records of Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe document was kept with the rest of the national records in Edinburgh Castle until 1612 but the Declaration was taken to Tyninghame as work got under way in the castle. Some say Sir Thomas moved the declaration for safekeeping, others have suggested he wanted to “peruse” it at his leisure.

The declaration remained at Tyninghame for more than 200 years – and, of course, damp took hold before it was finally returned to the National Records of Scotland for conservation, which closely continues to this day.

Despite its worn and fragile state, the words of the Declaration naturally retain their power.

Professor Broun said: “The Declaration of Arbroath is very selective, it is a very tight piece of prose.

“It is very carefully crafted to hit the buttons that the Pope would have recognised straight away, that the Scots were an ancient people, with their own king. It would have hit a chord with the Pope. It wouldn’t have seemed outrageous to him.

“Incredibly towards the end, there is almost this finger wagging going on, that if you listen to the tales of the English and allow the war to continue, you will have god’s wrath on your hands.

“It is an amazingly, incredibly powerful piece of prose. You have to imagine the Pope sitting there, listening to this being read out. For this is how it is written – to sound good.”

And, it worked, to an extent, with the Pope writing to Edward II calling for him to make peace with the Scots.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProfessor Broun said: “The corner had been turned. The Pope still didn’t recognise Robert I as King but the diplomatic pressure was off. It was the equivalent of the lifting of UN Sanctions.

“The Declaration of Arbroath had its moment, but we really celebrate it because of its afterlife.”

Adam of Montrose secured the document’s status as the “pivotal statement” of the right to Scottish independence when he compiled a dossier of documents in 1380 with the Declaration of Arbroath placed at the very front of that set of papers.

“It was soon part of the account of the nation’s history,” Professor Broun said.

“The significance of Adam of Montrose’s collection is that it was later copied as part of the standard account of Scottish history in Latin – in some versions it stood on its own, in others its contents were incorporated into the history itself,” he added.

But, for all its standing, the Declaration of Arbroath effectively disappeared out of the picture for around 350 years, according to Professor Murray Pittock, British cultural historian, pro vice-principal at Glasgow University and trustee of National Trust for Scotland.

Despite the weight of the Declaration, it broadly disappears after 1320, appearing only in “fragments” until the late 1680s.

“That is not unusual,” said Professor Pittock. “It was a document of its time. The Magna Carta disappears by the start of the 14th century and it comes back in 1603,” he added.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut as interest in the document revived, its political philosophy of freedom and authority of the people went on to have a deep and lasting reach.

“The Declaration of Arbroath is a document of its time with interest in it revived by successive generations of Scots. It seems likely that the declaration underpins the development of political thought in Scotland and the idea of compact between the king and the people,”

Professor Pittock said the ideas of Duns Scotus, a Catholic priest, philosopher and theologian during the Middle Ages, underpinned the declaration which then went on to influence other important political thinking.

“Duns Scotus is a great believer in personal freedom. He talks of people’s rights to choose their ruler and their authority to remove or change that authority.”

Aspects of the Declaration of Arbroath were used in the Claim of Rights of 1689, which sets out the constitutional principle that the monarch is bound by the law and was used to assert that James VII had forfeited the crown.

“From then until 1760, the Declaration of Arbroath is back into fashion significantly, it is widely in circulation, and you have political philosophers strongly using language like that of Arbroath,” Professor Pittock said.

Among them was Francis Hutcheson, philosopher and one of the “founding fathers” of the Enlightenment, whose work “very strongly influenced “ the ideas Thomas Jefferson and others who framed the American Declaration of Independence.

Professor Pittock said there was no “smoking gun” to connect 14th century Scottish political philosophy with 18th century thinking, with it only possible that Jefferson knew directly of the Declaration of Arbroath.

But its influence on popular US consciousness is clear.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, Tartan Day – which celebrates links between Scotland and the US – is celebrated on 6 April, the date the Declaration of Arbroath was drafted.

In 1998, Senator Trent Lott and the Coalition of Scottish Americans successfully lobbied the Senate for the designation of 6 April as National Tartan Day “to recognise the outstanding achievements and contributions made by Scottish Americans to the United States”.

A Senate resolution of 20 March, 1998, spoke of the predominance of Scots among the Founding Fathers and claimed that the American Declaration of Independence was “modelled on” the Declaration of Arbroath.

Today, it is marked by a grand pageant that winds through New York, with the city alive with talks and parties that mark the connections between the two.

Sean Connery and Billy Connolly have led the procession in the past, the modern icons of Scotland, some 700 years after Bruce made his way to the crunch meeting at Newbattle.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.