Hogmanay: Scotland enters the traditional 'daft days' that surround New Year

With Christmas long frowned upon by the Kirk for its frivolity, December 25 was not declared a public holiday in Scotland until 1958 as religious piety held firm over society.

Any activity that was judged to be extravagant, or celebrated superstitions, was deemed un-Christian and indeed illegal. In 1583 ,the Glasgow Kirk at St Mungo’s Cathedral, now Glasgow Cathedral, ordered the excommunication of those who celebrated Yule, whilst elsewhere in Scotland, even singing a Christmas carol was considered a serious crime.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

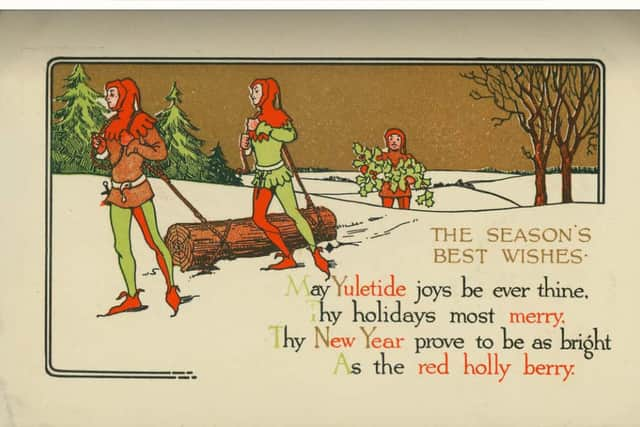

Hide AdBy the 1800s, people had become more relaxed about observing Christmas, but it meant the turning of the New Year was the true festive celebration. The 12 days between Christmas and Twelfth night were given over to merriment and excess, with the period hailed as the “daft days” by 17th-century Scots poet Robert Fergusson.

Cast an eye over accounts of New Year, from the Western Isles to Orkney to the farms of the lowlands, and you’ll find accounts of rituals, tradition and a sense of the wild as people indulged their freedom to celebrate. From tales of men wondering from house to house disguised as cows, to stories of standing stones that started to move at the stroke of midnight to the long, perhaps more familiar, boozy night as extra days off work were enjoyed to the full, New Year was Scotland’s party.

The daft days were also later referred to as “easy-going olden times” when no work was done and time was spent on “friendly festivities and expressions of good will”.

During this spell, which was known as Nollaig in the Highlands and Western Isles, a common saying was often shared: “The man whom Christmas does not make cheerful/Easter will leave sad and tearful.”

In Gaelic speaking areas, Hogmanay was referred to as either oidhche Choinnle (‘Night of the Candle) or oidhche nan Callainnean (‘Night of the Blows’). The latter may be linked to a ritual that involved a man having a dry cow hide placed over his head before being beaten like a drum as he and his friends moved around their home village.

Usually led by a piper, the group would move around each house, turning anti-clockwise, striking the walls and reciting rhymes to raise the householders. As doors opened, the group would pile into each home to receive refreshments such as oatmeal bread, cheese, flesh and a dram of whisky, according to John Gregorson Campbell in his encyclopedia of customs, The Gaelic Otherworld.

The idea was to “drown the animosities of the past year in hilarity and merriment”, Mr Campbell wrote.

Fire and light played a central role in belief and customs surrounding New Year. It was feared that letting the fire go out would invite bad luck into the home, with only householders – or a friend – allowed to tend it. If a fire went out, it was considered most unlucky.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn many districts on New Year’s Day, no help would be given to a neighbour to restart their flame. Letting the flame go out was broadly considered as giving away a gift from the gods.

New Year’s Day, like the first of every quarter of the year, was a great ‘saining’ day across the Highlands and Islands when rituals were at their most intense to protect cattle and houses from evil. Juniper was burnt in the byre, animals were marked with tar, the houses were decked with mountain ash and the door-posts and walls and even the cattle were sprinkled with wine.

In Orkney, there are legends of giants being turned into standing stones, which then moved when the clock struck midnight on December 31. In Rousay, the Yetnaseen, which translates as Giant Stone, is said to come to life and walk 300 yards to the Loch of Scockness to drink water, before turning to stone once again.

Lovers also visited the Ring of Brodgar on New Year where the man would fall to his knees and "pray to the god Wodden" that the couple keep the oaths they were about to swear. A ceremony of commitment would then take place at the nearby Odin Stone.

Many Scots considered Handsel Monday – the first Monday after New Year – as the great winter holiday of the year. For 500 years, it was regarded as a day of family and merriment with small gifts exchanged between neighbours and friends. The word “handsel” originates from the old Saxon word, which means “to deliver into the hand”.

With the holiday a great celebration among rural and farming folk, particularly in the Lowlands, it was usual for workers to be treated in some small way by their masters.

On Handsel Monday, half a crown or a shilling would often be collected from the big house, with a piece of cake and glass of toddy also shared while the bosses tended to the graft of the day. Fife and Perthshire were two areas of Scotland where Handsel Monday was celebrated long into the 19th century, despite New Year’s Day becoming the holiday of choice in cities such as Dundee and Glasgow.

There were no lie-ins, however, despite the day off. It was usual for workers to get up extra early, so they had as much time as possible to enjoy the holiday.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdVillagers were usually woken up by young residents kicking tin pans through the streets to mark the beginning of the day. Breakfast was fat brose, made from beef fat poured on oatmeal, with bonfires lit after the first meal of the day. Pubs drew large crowds and workers cast aside their daily lives to let the daftness in.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.