Gunpowder, tattoos and transportation - a study of Scotland's inked convicts

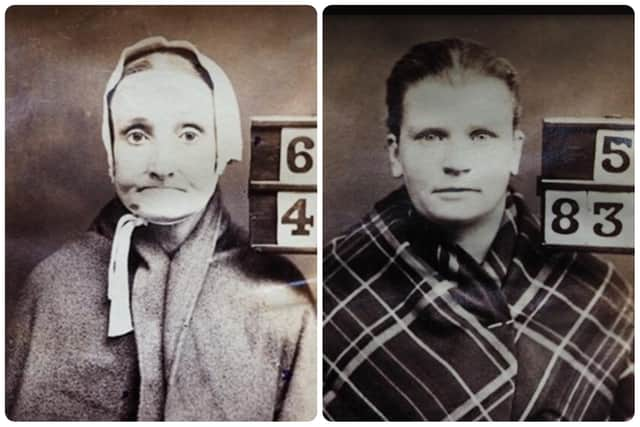

Included in Jane Johnston’s prison records are notes about her tattoos. On her left arm were the initials MSC, which were probably tattooed by own hand. On her right arm was the name Robert Lane. A lover, perhaps, or a partner in crime.

Johnston, of Aberdeen, was jailed in December 1882 for three months hard labour as a “rogue and a vagabond” and disappeared to Glasgow on release, her story then unknown.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut her papers and photograph from Perth Prison are now central to a new exhibition that looks at the long-explored links between tattoos – considered the ‘jewellery of the working class’ – and criminality.

The show, Gunpowder, Tattoos and Transportation: Aberdeen’s Inked Convicts, is a key draw of Granite Noir, the city’s popular crime writing festival, which starts on February 20.

Dr Ashleigh Black, archives assistant at Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives, has compiled the exhibition using records from Perth Prison and a register of transported convicts who found their way home.

She found numerous examples of the tattooed criminal class, with the marks likely to have been made from gunpowder, charcoal or ashes mixed with water, saliva or urine.

Dr Black said: “The most common tattoos were lettering, initials, numbers and dots, mainly because they were the simplest to tattoo and could be easily self-administered. Other common motifs were female figures, anchors, crucifixes, hearts, ships and flowers.”

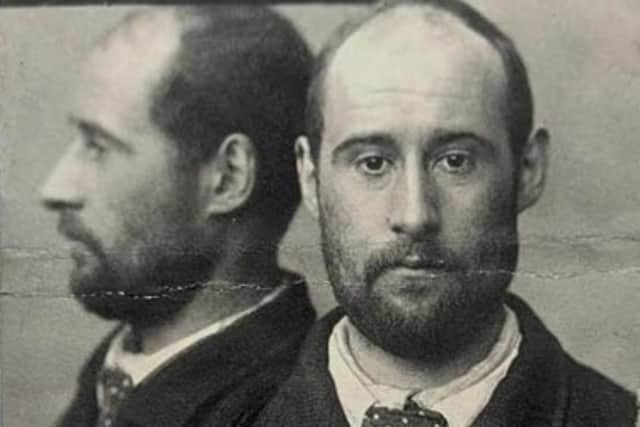

Dr Black said, while women typically were marked with names and initials, the tattoos of men tended to be more elaborate. Murdoch Grant, a seaman from Thurso, was sentenced to ten years penal servitude following a drunken quarrel on a schooner docked at Wick that ended in a fatal stabbing.

Prison records show Grant had a fresh complexion, black hair and brown eyes – and a tattoo of a horse, traditionally used to represent strength and freedom, inside his upper arm.

Meanwhile, John Stephen, who was transported from Aberdeen in 1866, was marked with a crucifix and sailor on his left arm and a woman on his right. While links between tattooing and the social underclass were made by 19th-century criminologists and phrenologists, Dr Black said she believed the tattoos were irrelevant to criminality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe said: “People, even back then, chose to get tattoos for several reasons, some of which may resonate with people today, such as commemorating a loved one or a friend or even something to remind them of home if they had to travel great distances.

"Tattoos were the jewellery of the working class – some of the convicts featured in the exhibition had tattoos of rings and bracelets, and as jewellery was an expensive commodity, getting a tattoo would have been a lot cheaper in comparison.”

Dr Black said a cultural shift in the perception of tattoos occurred at the end of the 19th century, with King Edward VII tattooed with a Jerusalem Cross and Princess Marie of Orleans marked with an anchor in support for her husband’s maritime career.

The Granite Noir programme presents a collection of author discussions, including Lisa Jewell and Marie Cassidy, Ireland’s first state pathologist, with events including an evening with Poirot star David Suchet.

For full details, visit www.aberdeenperformingarts.com/granite-noir

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.