The Edinburgh doctor who fought killer disease from his flat and brought hope to the world

Dr Robert Philip is remembered for his pioneering work in the fight against tuberculosis, a disease which was responsible for 10 per cent of all deaths in the Scottish capital in 1890.

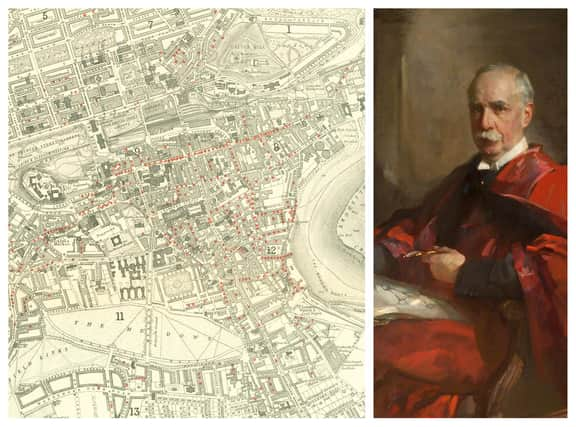

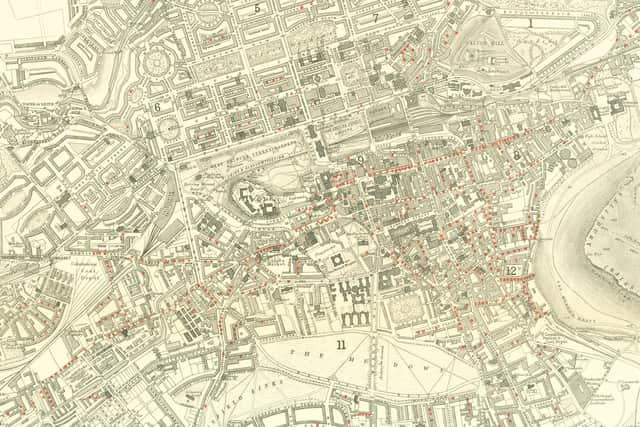

Now, the work of the doctor is being illuminated by National Library of Scotland, which has published online the breakthrough mapping exercise carried out by the doctor, who tracked patients and recorded the spread of the disease.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe data was used to inform his approach to treatment, which split patients into three broad catagories with many urged not to isolate in their homes but instead recuperate in the fresh air.

Chris Fleet, map curator at National Library of Scotland, said the disease was poorly understood at the time and popularly blamed on everything from prostitution to vampires.

"But even the well-educated tended to see it as a fellow-traveller of vice and sin," he said.

Dr Philip, who was born in Govan but relocated to Edinburgh as a boy, led the fight to better understand the disease and help its sufferers from the Victoria Dispensary for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest.

First located in a set of flats in Bank Street, Edinburgh, it moved to 26 Lauriston Place in 1891. This dispensary was the first preventative institution of its kind in the world, and particularly valuable for the poorer inhabitants of the city. In time, it was replicated throughout countries everywhere.

Mr Fleet said: "The way he analysed data on TB, and the way that he used, resulted in a dramatic fall in cases. He really set up the scheme to tackle the disease which was the replicated across Europe."

Dr Philip, the son of a minister, reported that Edinburgh’s medical provisions of 1892 were completely inadequate to the task of treating or isolating tuberculosis patients, with many sufferers being confined to their homes.

"If there be the slightest degree of truth in the contagious view of tuberculosis, such chronic foci of infection ought not to be permitted to smoulder under conditions which are calculated to encourage the fatal propagation," he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe argued that the best way to treat tuberculosis patients was to build up their general constitution and allow them to resist the infection.

Fresh air, clean surroundings, a nutritious diet, physiological rest and careful exercise were all preferred routes to beating the disease.

As a result, the dispensary employed nurses to attend patients at home and advise on such matters as cleanliness and diet.

Dr Philip was strongly of the opinion that the disease could be treated most effectively if it was caught early in its development.

"As he regarded the home as the main site of transmission, he used home visits as an opportunity tosearch out other cases by lining up contacts and examining them for signs of the disease—a procedurehe liked to call a 'march past',” according to the National Dictionary of Biography.

Dr Philip put TB sufferers into three categories. The really serious cases were put to the City Fever Hospital at Craiglockhart, which was set up in 1897 following pressure form the medic.

Early-onset cases were sent to a sanatorium, usually the Victoria Hospital for Consumption in Craigleith, later the Royal Victoria Hospital, which opened in 1894.

Funded by public subscription, it grew from 15 beds to more than 100 over the next 13 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose requiring isolation and rest were often sent to Polton Farm Colony, opened near Lasswade in 1910, where patients could engage in gentle agricultural work in an environment very different from their homes

Mr Fleet said: "These approaches are analogous with the different ways different countries are dealing with coronavirus.

"At the time TB was very poorly understood but Dr Philip really focused on the empirical data and how that can be best used."

Dr Philip's map plotted sufferers not by house but by neighbourhood in order to protect the confidentiality of patients.

The worst-affected areas were the Old Town and South Side, and westwards to Gorgie, in strong contrast to the New

Town and other outlying suburbs which had just a small scatter of cases, Mr Fleet said.

The map formed part of a detailed paper presented by Philip to the Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh in March 1892, synthesising vital statistics from the cases he had examined, and it was subsequently published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal.

Dr Philip’s mapping listed the occupations of these 1,000 patients. Less than 5% of the sufferers were children, while many others were not confined to poorly-ventilated environments or lower-income occupations, but represented a fairly wide cross-section of Edinburgh’s domestic economy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Fleet added that at least 15% of the victims could be described as lower middle class or above. If those listed as having occupations in publishing and clothing, the figure would rise to 29 per cent.

A total of 141 married housewives were included in his mapping of the disease - the single largest occupational category affected – were also presumably middle class in origin.

Dr Philip was able to record the results of treatment for 469 of the patients: around 58% were demonstrably ‘improved’, but 24% were described as ‘indifferent’, and 16% had deteriorated or died.

The doctor was widely regarded for his work on TB. He was knighted in 1913 and then appointed physician to King George V.

Click here to see a zoomable version of Dr Robert Philip’s map which tracked how the disease spread in Edinburgh.