Discovery of 11,000 pieces of stone tool illuminate Scotland's early people

A team of community archaeologists, who formed the group Mesolithic Deeside given their passion for all things related to these early inhabitants, worked alongside professionals to make the finds.

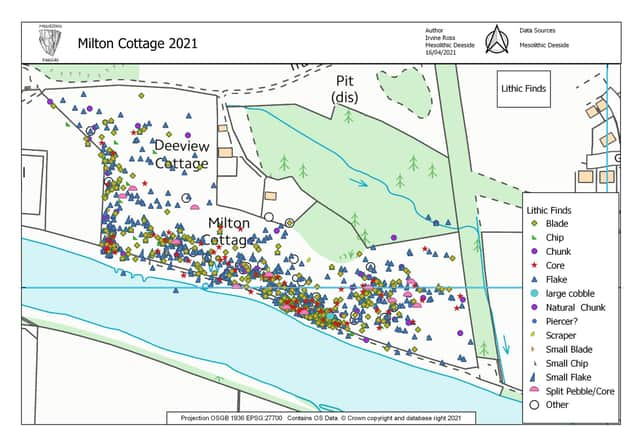

A total of 42 fields were investigated along the Dee Valley in Aberdeenshire, from which more than 11,000 lithics were recovered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe work has been credited with creating an “abundant” record of the hunter gatherers who lived close to the River Dee, which stretches from the Cairngorms to Aberdeen.

Archaeologist Caroline Wickham-Jones, in her final report on the project, which is published by Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, said small early prehistoric communities were living in the Dee Valley from around 13th millennium BC, a time of rapid climate change as the last ice age started to abate.

The Mesolithic Deeside project, along with other existing archaeological evidence, made it possible to build a strong picture of life along the Dee for the families who made it home over time.

In her report, Ms Wickham-Jones said; “The work of Mesolithic Deeside reveals an extensive archaeological record that comprises multiple traces of diverse activity throughout this landscape. This record is not and can never be complete, but in comparison with many other areas it is abundant.

“The prehistoric population of Mesolithic Deeside was not scattered, nor isolated. This part of the country was well able to support a thriving population over long periods of time.”

Early settlers came to the Dee during the Late Upper Palaeolithic period, when temperatures rose and the open landscape was dotted with some woodland, including birch and juniper.

Britain was then still connected to the continent by Doggerland, with evidence suggesting people travelled long distances in the course of an annual round.

They possessed detailed understanding of the landscape within which they lived, from which they derived all the resources necessary for survival, the report said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Wickham-Jones said: “Mammals such as reindeer are likely to have provided an important resource, and groups may have followed them and other species as they moved across the landscape.”

A stone weapon head found at Nethermills Farm near Crathes, Deeside, may be of a type linked to the Hamburgian culture of reindeer hunters from north-west Europe.

At the same site, slightly later Mesolithic finds were made over a stretch of 1.2 miles, making it among the most significant locations of the period in Britain.

By then, climactic conditions had improved, vegetation increased and mixed woodland and forest started to appear.

Population numbers grew and people still survived from the land, but fish and marine life became new resources.

Small stone blades were manufactured and a new range of bone and antler tools followed.

Ms Wickham-Jones, formerly of Aberdeen University, said the Mesolithic Deeside project had involved a wide variety of people, from children to professional archaeologists.

"In this way, the excitement of unearthing the ancient past has come to many,” she said. “The project has undoubted academic and archaeological benefits, but it has also resulted in much wider impact and this will, it is hoped, continue into the future.”

A message from the Editor:Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by Coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.