Alcohol advertising ban: Scotland's long love of the pub - and a 600-year mission to control our drinking

From 9pm curfews imposed on inns for travellers during the 15th century to the long measure of economic, moral and legal moves to break up the hold of alcohol consumption, the Scots’ love of a drink has been the concern of authorities for at least 600 years.

Historian Anthony Cooke, author of A History of Drinking, The Scottish Pub since 1700, said Scots have “long had a problematic relationship with drinking”, with state alarm heightened as populations intensified, whisky overtook beer as the drink of the working man and pubs became meeting places for the relaxed and the radical.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Scots have always found a way to keep drinking, with assertion of powers often creating more dangerous environments in the process. When the Temperance movement hit its peak in Scotland in the early 20th century, drinking widely moved underground.

There were reports of an explosion of shebeens in Glasgow, where spirits were commonly mixed with meths. Meanwhile, Wick in Caithness became “practically a huge shebeen” by 1933 after the town voted itself dry using legislation lobbied for by the sober movement.

Mr Cooke said: “They have been trying to control alcohol consumption in Scotland for a long, long time. Even before the Reformation they were trying to do it. Around 1424, the Scots Parliament was passing an act to set up inns for travellers and their horses. But by 1446, it seems to have been too successful as the parliament is then bringing in a curfew of 9pm on drinking spirits, beers and wine."

After the Reformation, the kirk session took to monitoring ale houses. In Balmerino in Fife, it was decreed in 1637 that any brewer selling ale before the end of Sunday service should pay 40 shillings ‘and make their repentance before the pulpit’. In Dundee, banishment was threatened to those caught twice drinking in a city ale house after 10pm.

Mr Cooke added: "The authorities for 600-plus years have been trying to regulate drink consumption, but usually with no too much success. The Scots were quite good at getting around it. People were very ingenious, right down the ages.”

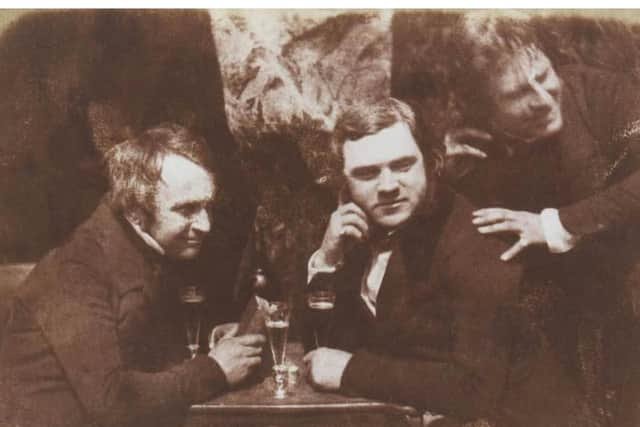

With pubs in Scotland long depicted as snug, convivial shelters for the storm weary, the dispossessed, the bawdy and jolly, the stronghold of the pub on Scottish life became of the highest concern in the early to mid 19th century.

As Scotland underwent rapid change with growing populations, movement of people and expanding urban areas driven by industrialisation and the hunt for work, the pub acted as an anchor in a nation in flux. Business was done, networks were formed, lodgings were found.

By 1820, ministers were complaining whisky had become the drink of the masses and magistrates struggled to keep ahead of the flourishing landscape of ale and spirit houses in growing industrial centres, from Glasgow to Dundee and Paisley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Cooke said: "People need to socialise, but of course there was great disapproval of it. The authorities feared the breakdown of law and order.”

He added: “Pubs were frequently viewed with suspicion by the authorities as places where the lower classes could gather to discuss unorthodox opinions, largely removed from the scrutiny of their social betters. In this way, pubs could act as a counter to the somewhat stifling hegemony of Presbyterianism, thrift, self-help, temperance and respectability that came to dominate 19th-century Scotland from the 1820s onwards.”

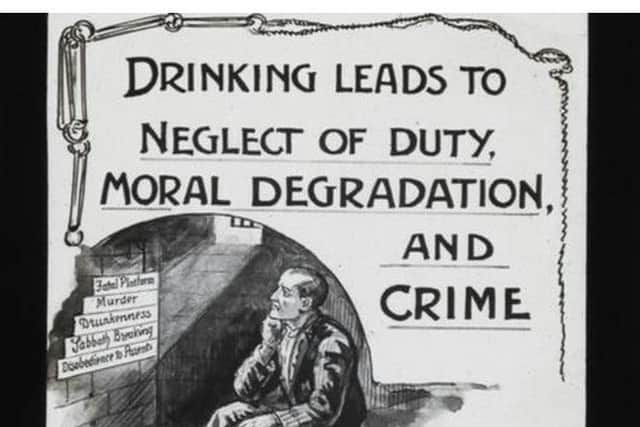

Around this time, the average consumption of legally-produced whisky in Scotland, by those aged 15 and over, was almost a pint a week. In response, the Temperance Movement was sparked, with the first anti-spirits society established in 1829 in Greenock – a town rapidly expanding given new arrivals from Ireland and the Highlands – by John Dunlop, a local lawyer with evangelist leadings.

Mr Cooke said: “One of the things Dunlop was very against was the paying of wages in pubs. The wives might never see any of it.”

By 1831, the Scottish Temperance Movement had 44,000 members. In the west of Scotland, the movement often carried “quite a strong Sectarian tone” in reaction to the changing demographic, with a priest arriving in Glasgow on a temperance mission in 1842, Mr Cooke added.

Temperance worked its way into legislation, not least given its high support from Liberals who held the vast majority of councils in Scotland in the early 20th century and believed heavy drinking demeaned the working man. Labour Party founder Keir Hardie, a Lanarkshire miner, became a temperance organiser given the heavy drinking of his stepfather.

By 1913, locals could vote to create dry towns and villages in “veto polls”. Among them were Cambuslang, Kilsyth, Kirkintilloch, Lerwick – and, of course, Wick. Kilmacolm did not have a pub until 1998.

The Temperance Movement joined with Sabbatarians to lobby for the 1854 Forbes MacKenzie Act, which fixed licensing hours between 8am and 11pm and Sunday closing was introduced for most premises. It was the blueprint for Scotland’s licensing law for the next 125 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn Dundee, arrests for Sunday drunkenness halved in a year, but much drinking went underground and the city held special courts purely for shebeens, Mr Cooke said. In Glasgow, where many pubs stayed open all night, a form of calm fell on the streets. However, in the following years, it was estimated some 1,600 shebeens operated in the city.

Mr Cooke said: “I think most experiences show it’s very hard to reduce alcohol consumption. The other thing is that most alcohol isn’t consumed in pubs. It is people drinking at home and drinking cheap offers from supermarkets. So the whole nature of drinking in Scotland has shifted.”

With drinking in Scotland already largely moved behind closed, unregulated doors, the alcohol industry – facing a ban on advertising – is working hard to keep its reach.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.