9 objects that link Scotland to slavery

Much work has been done to reinterpret items held in Scotland’s museum collections so their connections to plantation wealth and the suffering of humans held as slaves are no longer ignored.

Glasgow Museums has led the work with the city’s prominent role in the trading of goods manufactured by slaves – such as sugar and tobacco – affording rich material for its Legacies of Slave Ownership project.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome items are overt in their links, such as the silver slave collar manufactured in Glasgow and the the family portrait of wealthy ‘Tobacco Lord’ John Glassford that shows a black servant just making it into the painting.

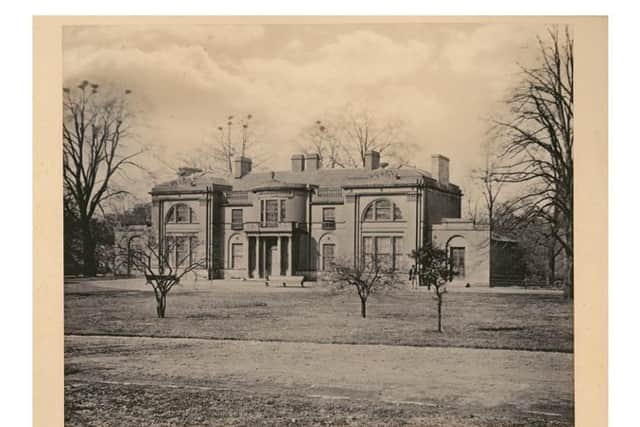

But behind seemingly benign museum pieces, such as a pictures of Kelvingrove House, which stood in the west end park when it was still a rolling country estate, lies a more hidden story.

The house is thought to have been built by merchant and former Lord Provost Patrick Colquhoun who worked all his life to promote slavery and exploitation.

“On at least one occasion one of his ships carried enslaved people from Jamaica to North Carolina,” said Katinka Dalglish, curator of archaeology.

By 1870, Colquhoun’s old mansion was refurbished into the city’s first municipal museum – the precursor of Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

A painting of the ship Medora reflects one Scot’s rise to great riches on the back of slavery. Owner James Lamont moved to Trinidad to make his fortune and became the island’s second largest owner of enslaved Africans.

In 1834, he received £17,000 compensation for almost 400 enslaved people following emancipation. He then purchased the Medora to transport his sugar and operated a shipping office in Glasgow.

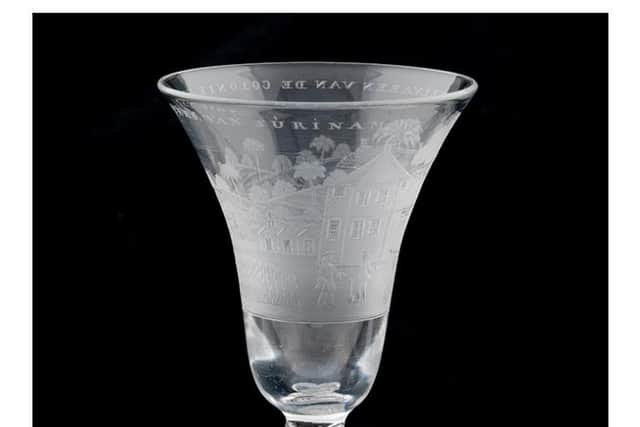

A drinking glass that celebrates the wealth of planters in Suriname, a former Dutch colony in South America where there was a large Highland population from the late 17th century, forms part of the city’s vast Burrell Collection.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile a painting – A Highland Chieftain: Portrait of Lord Mungo Murray – depicts the son of the John Murray, the Marquis of Atholl. Mungo died on the second expedition to Darien, his father a major subscriber to the scheme. A letter from 1699 to the directors of the Company of Scotland, which set up the colony, reveals the intended use of slaves for planting and labour.

A vivid purple dress also holds a hidden story. It was dyed with cudbear, a breakthrough purple dye extracted from orchil, with John Glassford, the wealthy Glasgow-based Virginia merchant, among financial backers of a cudbear dye works at Dennistoun in 1777.

Earlier that decade, a newspaper cutting details the escape of a 16-year-old enslaved boy, Boyd, from his master James Kippen in Glasgow.

Meanwhile, National Trust for Scotland has been looking at the use of Jamaican mahogany in its collection, including a George II bookcase at Castle Fraser in Aberdeenshire. For 300 years, the material was harvested primarily using the forced labour of enslaved Africans.

“These items, although beautiful to look at, have a far more complex history than may first meet the eye,” Dr Désha A Osborne, in an article for the trust, wrote.