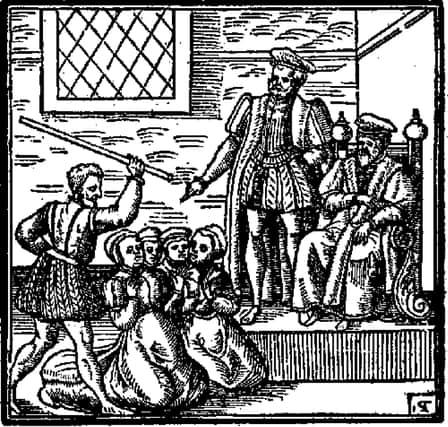

6 deviant women from Scotland through time

This reflected a widespread early-modern assumption that women lacked the strength, cunning and ‘killer instinct’ to commit really serious crimes, unless led or tricked into it by men.

Instead, female deviance was thought to be concentrated mainly in petty or disorderly offences like scolding or slander. But in reality, that was not always the case.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere Dr Allan Kennedy, lecturer in Scottish history at Dundee University and consultant editor of History Scotland magazine, looks are six examples of female criminals from 17 th -century Scotland.

Some were notorious, others were much more obscure, but between them they demonstrate that women, whatever people thought,were capable of committing just about any crime you could think of.

Jean Livingston, murderer

Born in 1579, Livingston married John Kincaid of Warriston and took the name ‘Lady Warriston’. The marriage was unhappy, and this drove Livingston, in conspiracy with her nurse, Janet Murdo, to arrange for her husband’s murder. They enlisted Robert Weir, a servant of Livingston’s father, to do the deed.

On 1 June 1600, after Kincaid had retired to bed, Weir snuck into the house and strangled him.

News of the murder travelled fast, and the next day Livingston and Janet Murdo were arrested .Weir would not be tracked down for another five years.

Both were convicted at a hastily-arranged trial, during which Livingston allegedly showed no emotion or remorse, and they were sentenced to death by strangulation.

Livingston’s family, despite enjoying royal favour, made no effort to intervene on her behalf, instead merely lobbying (successfully) for her to be executed in an early-morning beheading to save familial embarrassment.

Livingston allegedly repented her crimes eventually, spending her final day in prayer, but it made no difference: she was executed on 5 July 1600. Acause célèbre in its day, the case of ‘Lady Warriston’ is also a reminder that female deviance could sometimes take horrifically violent forms.

Marion Boyd, Countess of Abercorn, religious nonconformist

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn an age that tended to marginalise women, religion offered one of their most powerful means of self-expression. Moreover, refusing to adhere to the established Church of Scotland could thrust women firmly into the public eye – and that, ofcourse, could be dangerous.

Marion Boyd, the wife of James Hamilton, 1 st Earl of Abercorn, found this out to her cost. While the earl was Protestant, she was, verydangerously for the early 17 th century, a Catholic. And she does not appear to have been especially secretive about it: she regularly consorted with Catholic priests; lobbied the king to relax the penal laws against Catholics; and took steps to ensure her children would be raised Catholics.

Eventually, in early 1628, Lady Abercorn’s behaviour earned her excommunication by the Church. Soon thereafter she was arrested, spending the winter imprisoned in Edinburgh’s notorious Tolbooth.Released in 1630, she remained under virtual house-arrest at her home in Duntarvie, West Lothian to ensure that she had nothing more to do with priests.

After about a year of this confinement, she was permitted to visit Paisley, where she also had lands, but there she died, her health having been broken by her ordeals. Although she was never convicted of anything, the (ultimately fatal) harrying of Marion Boyd illustrates the dangers facing women with unorthodox faiths.

Isobel Gowdie, suspected witch

Witchcraft was one of the most sex-specific crimes of the early modern period; of the around 4,000 people accused of witchcraft in Scotland, perhaps 85% were women.

Isobel Gowdie of Auldearn near Nairn was probably the most well-known of these suspected witches, largely because her alleged activities was particularly fantastical.

In 1662, at the height of Scotland’s biggest ever witch-panic, Gowdie was implicated in a plot to bring magical harm to the local minister, Henry Forbes.

Over the course of four separate confessions given in April and May 1662, she confessed to having entered into a covenant with the Devil in 1647, and claimed that, since then, she had been part of a large and very active witches’ coven.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis group, Gowdie said, had practised a wide range of dark magic, for example ruining crops, with their activitiesculminating in the plot against Forbes. Her earlier confessions were also steeped in local folklore, liberally describing various adventures with fairies and elves.

We do not know for sure what appended to Isobel Gowdie, since the records of her trial, scheduled for the summer of 1662, have been lost. But her rich and multi-layered confessions make her one of the most fascinating witchcraft suspects of the earlymodern period.

Jean Weir, witch-consulter and sex criminal

Illicit sex was enthusiastically punished in the 17 th century, and in most cases the acts being targeted – for men but even more for women – were things like fornication and adultery.

But every so often, a more serious case emerged, and none was more sensational than that of Major Thomas Weir, who was executed in 1670 for a litany of sex offences. The most serious of Weir’s many crimes was maintaining a long-term incestuous affair with his sister, Jean. This allegedly began around 1620 when Jean was barely more than a child, and continued for upwards of 30 years, the two regularly holding assignations in and around Edinburgh.

In the meantime, Jean – who remained unmarried – set herself up as a schoolmistress in Dalkeith, and whilethere got into the habit of consulting with witches.

In particular, she solicited from one supposed witch a small piece of enchanted wood that allowed her to spin impossiblylarge volumes of yarn.

The whole affair came to light when Thomas Weir, at about 70 years of age, felt compelled to unburden his conscience by coming clean.

When confronted with her brother’s confession, Jean followed suit. The pair were put on trial together on 9 April 1670, inevitably found guilty, and sentenced to death, thereby ensuring that Jean Weir would become arguably the most notorious female sex-criminal in Scottish History.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBessie Brebuer, child-killerOne of the most stereotypical ‘female’ crimes of the early modern period was infanticide. Indeed, almost everybody tried for child-murder in the early modern period was a woman, and it was an act that, by subverting women’s expected roles as mother and carer, inspired deep horror.

Among the many infanticide cases of the 17 th century, that of Bessie Brebuer is particularly striking. A young woman ofunknown background, Brebuer lived in Ballindreich, Fife, and was accused of murdering a new-born baby girl by ‘stopping [her] mouth with sand’. The motivation behind Brebuer’s crime was both obvious and all too typical: the child was her own daughter, and had been conceived as a result of an extra-marital affair with an unnamed man.

Baring a child out of wedlock was little short of a disaster for 17 th Century women, all but ensuring social and reputational ruin, and so Brebuer musthave felt that she had little choice but to dispose of her baby.

But the consequences were terrible: she was tried before the High Court on 17 July 1663, rapidly convicted, and sentenced to death by hanging.

Barbara Phinnick, fire-raiserThe crime of ‘wilful fire-raising’ – the Scots Law term for arson – was an almost exclusively male preserve in the early modern period.

But among the small band of female fire-raisers was Barbara Phinnick, a domestic servant in the household of the wealthy Edinburgh couple Mr and Mrs James Stampheild.

Phinnick seems to have developed a dislike of her mistress, and was at one point caught stealing fabricsfrom her. Mrs Stampheild forgave her and kept her in-post, but this show of mercy only enraged Phinnick further. She therefore resolved to set fire to a property owned by the Stampheild’s near the Netherbow, which she did in May 1670 by leaving alighted candle in one of the beds. The blaze was discovered before any great damage could be done, but Phinnick’s actions could potentially have beendisastrous.

She was tried before the High Court on 8 July 1670, and during her hearing she freely confessed to the crimes alleged against her. For some reason, the result of her trial is not recorded, although since the proscribed punishment for wilful fire-raising was death, we are probably safe in assuming that Barbara Phinnick ultimately met her fate at the hands of the hangman.

Like ‘Lady Warriston’ 70 years earlier, Phinnick is a useful reminder that stereotypically ‘female’ crimes were neverthe only offences of which 17 th -century women were accused.