Protein that works on mice could be key to treat Alzheimer's

Researchers from Glasgow University and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) discovered that injections of the protein IL-33 could improve cognitive function in mice with Alzheimer’s-like disease.

There is no cure for the neurological condition, which is characterized by plaque deposits and tangles of toxic protein in the brain, leading to the death of nerve cells and loss of brain tissue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia, which affects around 90,000 people in Scotland.

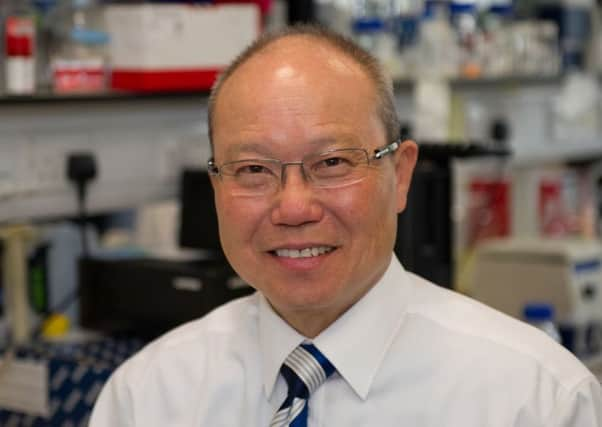

Glasgow expert Professor Eddy Liew discovered the IL-33 protein could digest existing plaque deposits and prevent the build up of new ones, which led to an improvement in memory and brain function among mice within a week.

Professor Liew said: “The relevance of this finding to human Alzheimer’s is at present unclear. But there are encouraging hints.

“For example, previous genetic studies have shown an association between IL-33 mutations and Alzheimer’s disease in European and Chinese populations.

“Exciting as it is, there is some distance between laboratory findings and clinical applications.”

The IL-33 protein is produced mostly in the nervous system but patients with Alzheimer’s had less IL-33 than people without the condition, he said.

The study, published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA (PNAS), also found the IL-33 curbed the inflammation in the brain tissue, which has been shown previously to increase plaque and tangle formation.

Experts hailed the findings as “a promising avenue of research”, but were quick to caution that there was a long way to go before this could be applied to humans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDementia expert Professor June Andrews, emeritus professor at Stirling University, said: “It is fantastic that Scottish researchers are making progress in the basic science that might one day lead to a cure, although they are right to be cautious about their results.

“In the mean time it is important to plan for increasing numbers who will need help before a cure is found.”

Jim Pearson, director of Policy and Research at Alzheimer Scotland, said: “While the initial findings may be promising, this is still the very early phase of the research and we look forward to hearing more from the clinical trials.”