Insight: Will women's health finally be taken seriously?

When we speak the following day, Bryden, who lives in Glasgow, tells me her problems began three years ago. After repeatedly visiting her GP about her abdominal pain, she was eventually sent for scans. One of those scans revealed the fibroid, which was smaller back then. But fibroids don’t always cause pain, so the doctors were unconvinced it was responsible.

She was told the pain would go away by itself, which it did for a bit. A year later, it returned, but she continued to be ignored. One doctor told her she was probably constipated, another that the drugs she needed might impact on her fertility.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn February 2020, she pitched up at A&E, doubled over. She was referred to a gynaecologist who – she says – took her seriously for the first time. He agreed she needed an operation, but said the fibroid was now so big it would be better to try to shrink it first.

She was told she should have hormone injections and come back to his clinic in three months. But, by then, the pandemic had taken hold and the clinic was cancelled.

At her last scan in May, she was told the fibroid was degrading, which can cause further painful complications. But she still has no date for surgery..

“I phoned two days ago and they said July was fully booked and they couldn’t guarantee August,” Bryden says. “I can’t walk, I can’t work. I can’t think. I am almost out of sick pay. I can’t live like this.”

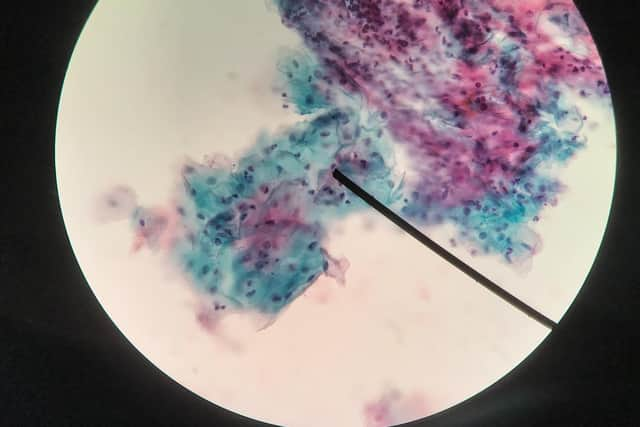

In Oban, Lorraine King, 50, a former nurse, is also waiting. She had an abnormal smear test in December and needs a colposcopy (a procedure to look at the cervix). Normally, this would take six to eight weeks, but a pandemic-related backlog means the waiting list is much longer.

She now has an appointment for the end of July – 32 weeks after her smear test. “I’ve tried not to worry, but you can’t help it sometimes,” she says.

To complicate matters, King is menopausal. She started experiencing symptoms at the age of 45, becoming anxious and low, and was given antidepressants. “I said to my doctor: ‘Do you think it could be the menopause?’ but he said: ‘No, you would be having hot flushes’, and I wasn’t.” Five years later, she is on HRT and has an appointment for a specialist menopause clinic in August.

Bryden and King’s negative experiences are born of systemic discrimination. For decades, gender inequalities have impacted on women’s healthcare, with men often treated as the default patients. There is a long history of women being under-diagnosed with heart problems; of pain being dismissed or misdiagnosed, and the need for pain relief going unmet.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRight now, the Scottish government is working to rectify these deep-rooted problems. It has promised its Women’s Health Plan will be published within the first hundred days of this administration – ie before August 16. But it will have to implement this plan against the backdrop of a pandemic which has caused backlogs in most fields.

So what can it hope to achieve? Will it help improve treatment of neglected conditions? Or will its good intentions be overwhelmed by the sheer challenge of dealing with the Covid fall-out?

Deputy chair of BMA Scotland, Dr Patricia Moultrie, says the gender imbalance is rooted in traditional medical research and education. “In times gone by, it was largely men that were entered into clinical trials so a lot of research was done on cohorts of men,” she explains.

“And women’s health issues were seen as a separate topic only some doctors would need to be familiar with. As a result, there was limited teaching on women’s health in the curriculum. On top of that, there were general societal factors – women’s interests simply weren’t considered as important.”

This attitude is reflected in the eight and a half years it takes, on average, for women in Scotland to get an endometriosis diagnosis. This despite the condition affecting one in 10 of the female population. It can also be seen in the plight of those struggling with the symptoms of the menopause.

“We carried out a survey which found women felt they and their doctors were under-informed about the menopause,” says Emma Ritch, executive director of feminist policy and advocacy organisation Engender. “They talked about being fobbed off and told: ‘It’s a normal stage of life – just suck it up’.”

The last couple of years has seen a shift driven by high-profile campaigns tackling once-taboo subjects. In her book, Invisible Women, Caroline Criado-Perez highlighted how women were 50 per cent more likely than men to be misdiagnosed after a heart attack. This is because those symptoms seen as “typical” – such as crushing central chest pain – are those experienced by men. Women do experience chest pain, but are more likely than men to experience shortness of breath and nausea. Heart attacks are seen as a male disease. In fact, women are three times more likely to die of heart disease than breast cancer, but most of them don’t know that, so far fewer end up in treatment.

There have also been books and TV programmes on the menopause. Still Hot!, a collection of menopause stories written by Kaye Adams and Vicky Allan, and Kirsty Wark’s Menopause and Me documentary, have underlined the need for more consistency in the training of GPs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSocial media has helped remove the stigma from talking about periods and other bodily functions. Last week, a frank online discussion sparked by Perez and the writer Caitlin Moran raised awareness of the pain some women experience when having intrauterine devices (IUDs) fitted.

“I think people have been able to talk more openly," Moultrie says. "And seeing other people talk more openly is crucial because it gives women and girls confidence to bring these issues forward and ask for help.”

At the same time, an increasing number of women have reached positions where they can influence policy. The Scottish government’s Women’s Health Plan was driven by former Health Secretary Jeane Freeman and the then chief medical officer Catherine Calderwood, whose background is in gynaecology and obstetrics.

Experts have been asked to focus on four main areas: sexual health, contraception and abortion; menstrual health and endometriosis; the menopause and heart health.

Since they began their work, Covid has altered the landscape. Not all the changes it has wrought have been negative. Temporary measures were introduced to allow some women to take early medical abortion tablets at home after an online consultation with a doctor. Previously, the women had to take the first of two pills in a clinic. There has been good feedback from those who used the service, but is not yet clear if it will continue beyond the pandemic.

The increase in online GP consultations has also made it easier for women with caring responsibilities, although it is important to ensure those who lack digital access aren’t disadvantaged.

“I have been aware of girls still at school who have been able to find a moment in the day where they can phone and ask for help," says Moultrie, who is also a sessional GP. "In the past, they might have been concerned about coming to the surgery, particularly if there was a chance of bumping into their mother’s friends.”

But Covid 19 has also caused huge backlogs across the NHS due to cancelled appointments and operations. These backlogs are not confined to women-specific conditions. In the first quarter of this year, 17 per cent of patients requiring urgent treatment for suspected cancers were not treated within the two-month target time – the highest level in two years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe backlogs are much worse for non-urgent – but still important – operations such as hip and knee replacements. But they are also impacting on some of the areas at the heart of the Women’s Health Plan. Those women who contacted Scotland on Sunday told of long waits for:

Laparoscopies (the procedure used to diagnose and remove endometriosis) Colposcopies and operations to remove fibroids.

Particularly hard-hit were sexual health services, with some reporting long delays in securing the coil or other contraceptives. “My contraceptive implant was due out in April, but I was told research said the implant could be effective for four years instead of three and this side of the sexual health clinic was closed,” wrote one woman, who didn’t want to be named. “My doctor confirmed the study of the four-year implant success rate had been on a very small group and wasn't reliable.

“[So], I am forced to keep the implant inside me and now take a pill in addition to this with the same hormone as in the implant to relieve the effects of having a depleted level of a synthetic hormone I cannot get taken out of my body by the people who put it in.”

Another woman told how she struggled to get hold of contraceptive pills. “It took two weeks for the GP to finally ring me back, a further month before I received a blood pressure check (required before a prescription can be issued),” she said. “I have still not received my prescription. The last time I chased it was two months ago and in that time I’ve fallen pregnant. I am gutted.”

The woman said she planned to continue the pregnancy but that her financial situation was precarious. “We’re in a three-bedroom house with a three-year-old and a one-year-old and my husband is already using our third room to work from home. So we’re quite crammed together. It’s very stressful."

Several recent scandals have tarnished Scotland’s record on women’s health.

Last month, it emerged a number of women had developed cervical cancer – and one had died of it – after being wrongly told they did not need to be screened. Maree Todd, minister for public health, women’s health and sport, said a “serious adverse event” in a cervical cancer screening programme meant at least 430 women had been wrongly excluded from testing over the last 24 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany of the cases involve partial hysterectomies where part or all of their cervix was left in their abdomens.

Todd said all the unscreened women would be offered urgent appointments with their GPs or gynaecologist. But cancer screening services are already overstretched with a backlog of about 180,000 delayed tests.

Also damaging has been the Scottish government’s response to the hundreds of women who have suffered serious and debilitating side effects from mesh implants fitted to tackle incontinence and prolapse.

Some of the women now use wheelchairs. They have lost careers, homes, marriages. For seven years, they have been campaigning for acknowledgement and redress. They have raised awareness, forced the Scottish government to ban the procedure and secured compensation.

Every small victory has been hard-won. But at last, the full scale of their trauma is being recognised. A new Bill recently lodged at Holyrood would allow the Scottish government to reimburse those women who had their implants removed privately.

It would also allow women who preferred to have mesh removal surgery outside of the NHS in future to do so free of charge, with travel costs paid for.

The NHS in Scotland has its own mesh removal service, but some of the women say they have been so badly let down they no longer trust the NHS to resolve their problems.

The mesh survivors’ trust in the NHS was damaged because their symptoms were initially dismissed. This is also true of many of those who suffer from endometriosis. Leah Franchetti suffered heavy, painful periods lasting up to 12 days when she was a teenager, but was told to take paracetamol and mefenamic acid and get on with it. At one stage, she was given tablets for Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was only when she met her current partner that she began to realise what was wrong. Her partner had also suffered endometriosis and recognised the symptoms.

In April last year, Franchetti was in such pain she ended up in A&E. She was referred to a consultant, but her appointment was cancelled because of the pandemic. The following March with no new appointment in sight she opted to go private on her partner’s healthcare. She had a laparoscopy in May. “The surgeon told me there had been endometriosis there for a long time – it should have been removed years ago,” she says.

Franchetti, a former Labour candidate, says she worries about the younger women she knows who are taking out loans to have their surgery, and hopes the Women’s Health Plan will make an impact. “One of my friends saw her GP last autumn and had an ultrasound three weeks ago, but it’s going to be months and months before she sees a consultant, never mind gets a laparoscopy, so the government is going to have to invest a lot more money. And we need more research, too.”

Emma Cox, the CEO of Endometriosis UK, is on the menopause and menstrual health sub working group of the Women’s Health Plan. She says the length of time taken to diagnose endometriosis means multiple GP appointments, multiple hospital appointments, going to A&E several times. “I think with more attention it could streamline the process."

Cox points out the SNP made a manifesto commitment to reduce diagnosis time and says if the NHS in Scotland met the NICE/SIGN guidelines and quality standards for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, it would make a real difference. She says the charity has been doing some work with the Scottish government to identify the barriers to their implementation.

“Another thing that would make a real difference would be if young girls were taught to recognise the symptoms” Cox says. “In England, we managed to get it included on the school curriculum. It is not yet included in Scotland but we are pushing for that to happen.”

Vicky Allan started collaborating with Kaye Adams on Still Hot! after experiencing her own menopausal symptoms and realising no-one had ever told her what to expect.

“Then I started to hear the more extreme stories of people who have been given antidepressants instead of HRT," she says. "And stories from people in the medical profession about how little mandatory education there is for GPs on this."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe had different experiences with two GPs - one who had little knowledge and one who took a special interest in the menopause. “It shouldn’t be a lottery," Allan says. "You shouldn’t have to find a GP with a special interest in something that affects 52% of the population.”

She says she thinks the conversation had started to shift before her book was published and that women are more confident about asking for HRT now than they once were.

The Women’s Health Plan is expected to say women should have access to a specialist menopause service if required and that there should be at least one person in every GP practice with a special interest in the menopause.

It is also expected to recommend more cross-speciality working, so cardiologists seeing women with complex heart disease would be able to refer them for contraceptives or menopausal care while pregnant women with high blood pressure could more easily be referred to cardiology.

This all sounds very positive, but, with the NHS facing the biggest challenge in its history, is it all pie in the sky? Perhaps inevitably, those involved in developing are optimistic. They say some of the recommendations don’t involve much extra resource and that work is already being done on short, medium and long-term implementation plans.

Others say the current crisis increases the urgency. “It’s coming at a very difficult time as we deal with Covid,” Moultrie says. “There are going to be a lot of competing priorities. But in a way that’s all the more reason for having a coherent women’s health plan: to help keep [women-specific conditions] on the agenda; to push for them to get the attention they deserve.”

ends

The 34-year-old needs an operation to remove a fibroid. It measures 12cm by 12cm by nine cm. She has been waiting for 14 months.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.