Coronavirus: Panic will only add to our problems – Bill Jamieson

For anyone in the front line of mental health, it takes time to change individual behaviour. In drink and drug abuse in particular, it can take years of education and patient care for personal habits to change. And even now, the incidence of addiction is higher than ever.

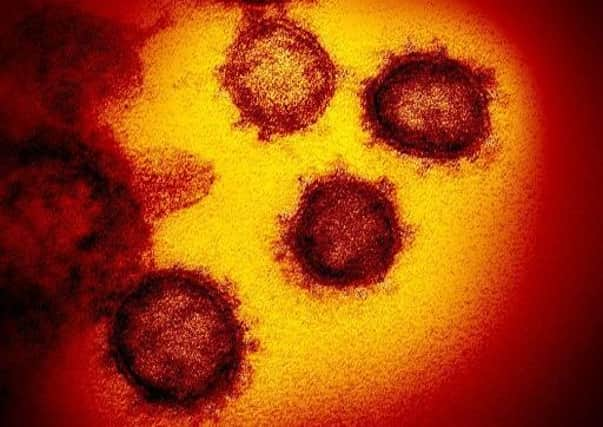

Yet in the space of a few days, the everyday behaviour of millions has shifted. Massive coverage of the coronavirus – its incidence, its spread and the warnings from the government this week that millions could be affected – has wrought a huge change.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe elderly and those with existing medical conditions are at most risk. From the cancellation of sports fixtures to checks at airports and borders, companies having to prepare for high absenteeism, stockpiling of food and cancellation of travel plans – and the intense, relentless admonition of hand-washing as demonstrated by government ministers – there are few who are not now aware of the spread of the contagion. Multiplying outbreaks affecting schools and medical centres leave no room for complacency.

The incidence of death among those affected may seem small in percentage terms – ranging form 0.7 to four per cent, depending partly on the quality of health care available – but if millions are affected, the number of fatalities can swell rapidly.

Little wonder we have seen behaviour change. And in terms of longer-term public attitudes to risk in a globalised world, it may prove a game-changer, bringing in new laws and government-spending priorities, encouraging self-sufficiency in food and manufacturing and boosting the reach and powers of international institutions.

It is a powerful demonstration of what fear can do, and on a global scale. Much of it is driven by fear of the unknown.

When questioned on how far the coronavirus will spread or what its immediate and long-term effects might be, the phrase that falls instantly from the lips of those we turn to for reassurance – from health experts, epidemiologists and government ministers is “it’s too early to tell”. And it is this admission of the unknown that is the most unnerving feature.

Given all this, there lurks a greater danger – that fear turns to panic, with widespread, unpleasant consequences. Airline travel is already sharply down and airlines are cutting back on scheduled flights this month and next. School holidays are being disrupted. Panic buying in the shops, not just of anti-bacterial handwash gels, face masks and paper tissues but of staple foods such as rice and pasta, is already evident. So, at what point exactly, does rational fear turn to panic?

Governments and official bodies need to take care that measures taken in response to the coronavirus do not themselves promote greater fear across the public. A classic example this week was the announcement by Jay Powell, head of the American central bank, the US Federal Reserve, to cut interest rates by a far greater than expected half a percentage point. The move was well-intentioned – to reassure businesses and the public that it was acting swiftly in response to a global economic slowdown. And in the face of the 2008-09 global financial crisis it worked – after a fearful pause – in cauterising the crisis and avoiding the worst of the forebodings at the time.

The hope was that this time around similar action would bolster confidence and extend a powerful rally already underway at the start of the week. The world economy is facing a sharp downturn. Reports indicate freight activity on some routes is down 20-40 per cent on normal levels and Chinese imports may be down around 12 per cent in the first quarter. On some estimates, world trade might shrink by as much as seven per cent year-on-year in the coming months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut instead of the rate cut bolstering confidence, the recovery was stopped in its tracks and share prices plunged again on fears that the effects of the virus may be worse than so far admitted. Why such a dramatic reaction? Traders began to ask that most sulphurous of questions: what is it that they know that the rest of us don’t?

In any event, there are doubts that an easing of financial conditions will do much to boost the supply side of the economy when people movement is restricted and firms hit by widespread absenteeism. The lesson here is that a more measured response would have worked better in terms of market psychology, while reserving more firepower should conditions deteriorate in the weeks ahead. Countering complacency is one thing. Acting in a way that may feed panic is another.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.