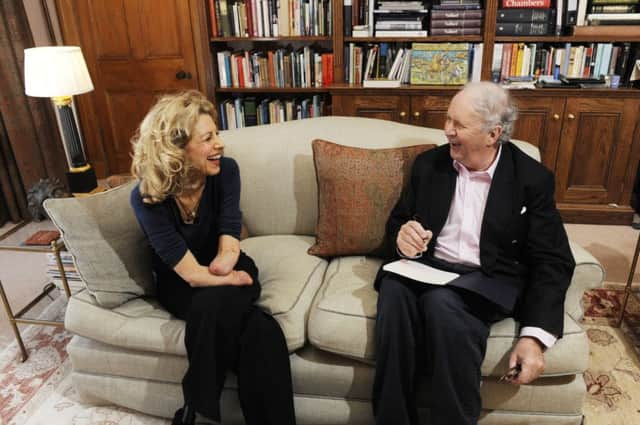

Alexander McCall Smith meets Olivia Giles

Olivia lives just round the corner, and I bump into her in the street from time to time. This encounter, though, has been planned: I want to know more about her and the exceptional things that she does. In particular, I want to find out more about the series of more than a thousand dinner parties that she is busy arranging. One thousand? “It was going to be five hundred,” she says, with a smile. “But I’ve decided to go for a thousand.”

“Hold on,” I say. “Let’s go back to the beginning…”

…which was 1987. Olivia, having graduated with a degree in law from the University of Glasgow, started her solicitor’s traineeship with the firm of Morton Fraser in Edinburgh. At the end of her training period, her first job as a qualified solicitor was with the Edinburgh office of the Glasgow firm, Maclay Murray & Spens, where she was employed in the commercial property department. She felt that she had found her niche: doing the legal side of property deals may not be everybody’s idea of fun, but it can be a high-octane branch of legal practice that is much relished by those who work in it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the beginning of 2002, when disaster struck, Olivia was a well-known figure in Edinburgh legal circles, an extremely attractive young woman who was doing very well in the often very demanding world of commercial property law. Of course her success came at the price of personal sacrifice: when transactions were in full swing nobody left the office, and it was not unusual for Olivia to find herself still working at midnight.

In February of that year, Olivia now feels, her immunity may have been at a low ebb because of the impossible hours she was putting in. “I fell ill at my desk,” she says. “I saw a doctor, but it was not until after the consultation that I noticed the tell-tale rash that had appeared on my feet.”

Everything then happened very quickly. By late afternoon she was in hospital and shortly afterwards she slipped into a coma. Her parents and her partner, Robin, were presented with the grim diagnosis: meningococcal septicaemia. The doctors at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary broke the grave news to her family that the likely outcome would be that even if she recovered consciousness, Olivia would be left without any limbs. The kindest course of action, perhaps, might be to let her slip away.

The next morning a highly regarded Edinburgh plastic surgeon, Awf Quaba, arrived for duty. He impressed the family with his determination and said that he thought he had a chance of saving Olivia’s elbows and knees. He would, he said, work to save the upper joints. Olivia remained in a coma for a month. When she came to, she found herself a quadruple amputee; the surgeon had saved her life but the price of this heroic medical intervention had been heavy.

It is sobering to imagine how one would react to such news. Many of us, I suspect, would be tempted to curl up and die. Many would, at the very least, feel profoundly miserable. Olivia is by no means a Pollyanna, but none the less describes how her overwhelming feeling was one of gratitude. “I was alive, which was the important thing,” she said. “And most of all I remember thinking how lucky I had been. I was told that at a number of crucial points, things had gone my way when they might not have worked at all. It was like throwing six after six in a game of dice.”

But what now? Long months in hospital followed, and there was the fitting of two prosthetic devices that would enable her to walk. There was also learning how to tackle simple tasks like taking food and water, opening doors, and so on, without the use of hands. Every step along this road was a challenge, but she did it. She could return to work now, but she realised that with the best will in the world, clients and colleagues in the legal world would find it difficult to treat her in the same way as they had before. “It’s unfortunate,” she says, “but some people would be concerned that you might not be able to do things as well as others.” She decided that it would not be realistic to attempt to pick up professionally from where she had left off.

It was not just that other people’s attitude to her had changed: her own view of what her life should be had been transformed. What had happened to her was a crushing blow, but she was now concerned with making something of the life that had, almost miraculously, been given back to her. That might have taken her in any number of directions, but for Olivia the road ahead was very clear – she would devote herself to doing something about meningitis awareness. Had she known more about the illness she might have been able to deal with it more timeously and then… But she was not interested in thinking about what might have been – her concern was to help others be more aware of the symptoms of the condition that had robbed her of so much.

Over the next few years, Olivia proved tireless in her fund-raising efforts for meningitis causes. She discovered a talent for organising big events, including a sponsored 12-hour, non-stop Strip-the-willow that raised half a million pounds. After that there was a return to hospital for a few months that made her think again of what she should do with her life. She had done her bit for meningitis research; now she decided that she would help amputees. In particular, she wanted to help those who lived in countries where little or no funding was available for prosthetic devices. In such places, the loss of a limb could amount to a sentence of unremitting hardship and even death.

Malawi

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOlivia decided she would do something about that. Her thoughts turned to Malawi. This small African country has a long history of engagement with Scotland – a story recently explored by Julie Davidson’s book on Mary Moffat, Livingstone’s wife. David Livingstone, the greatest of the Scottish missionaries, is still revered in Malawi, where his humane battle against the slave trade and sickness are considered a very positive aspect of the country’s history. As it happened, Olivia’s father had been born in Blantyre – the Scottish Blantyre, that is: there is still a Blantyre in Malawi. She looked into the situation of amputees there and realised that it was very hard. Malawi has a very small annual health budget for its people, and in circumstances where even aspirin or basic antibiotics may be hard to come by, the provision of artificial limbs is fairly far down the list of priorities.

On her first trip to Malawi in 2008, Olivia saw something that brutally brought home to her the plight of amputees there. The vehicle in which she was travelling drew up at a traffic light and she saw at the edge of the road a man who appeared to be living in the gutter; filthy and in rags, passers-by were clearly avoiding him. He had lost a leg and could not walk.

“The sight brought back to me the secret horror I had when I first came to understand what had happened to me,” she says. “It was a fear of being left to crawl on the ground like an animal. It was a fear of losing my human dignity.” In her discussions with the local Ministry of Health, Olivia discovered that there was a prosthetic device workshop in Malawi, but its staffing and its output were very limited. Effectively the care it provided was a drop in the ocean of need. She would do what she could to change this.

Back in Scotland, where she set up the charity 500 miles, she showed her skills for winkling out help. A generous Glaswegian supporter presented a building made out of conjoined freight containers. She could have this as her workshop, he said, if she got it out to Malawi and had it assembled there. Olivia could – and she did. Not only did she set up a new workshop, but she found the necessary manufacturing equipment tucked away in a store there – the gift of the Norwegian Government and unused because… well, there are any number of ways in which aid schemes can go wrong in Africa. She returned to Malawi to oversee the construction and fitting-out of this workshop. Staff were borrowed from the existing centre and they helped to train new technicians. At first only a trickle of devices were made, but this soon increased. At the end of 2009, the workshop was making 40 to 50 devices each month; now that figure is around 100.

Olivia tells me about some of those who have been helped. Like most stories of hardship in Africa, there are several aspects of these accounts that leap out at one. The first is the sheer resilience of people who are accustomed to deprivation. In our own society we take so much for granted, and are very ready to complain. In a country like Malawi, people make the most of what little there is and can show extraordinary dignity in coping with hardship. The other striking thing about these stories is how much of a difference a very small amount of help may make.

Olivia tells me about a girl called Susan Banda, who had been born with deformed legs that would never be capable of bearing her weight. The foster parents to whom she had been handed over did their best for her and managed to get hold of a wheelchair. They lived, though, in a village in which the ground was rough and broken, and the wheelchair simply got stuck in the sand. At the age of 16 she was taken to a hospital where her legs were amputated and an attempt was made to fit her with prosthetic devices. When she returned to her village, though, her stumps shrunk and the artificial legs proved useless. The family could not send her back for this to be remedied, and so she remained immobile.

The story might easily have ended there, but for the decision of Olivia’s charity to build a second workshop not far from Susan’s home. Susan managed to get a message to the men who were beginning to work on the building. Could she be remembered once things were up and running? She was, and with the legs they made her she was able to get herself to school and begin her life. And the cost of this transformation? Olivia gives me the figures. “In this country,” she says, “an artificial limb would cost about £4,000. In Malawi, we can make them for £75.”

We get round to the night of the thousand dinner parties. “What we are doing,” Olivia explains, “is asking people to invite a group of friends round for dinner – everybody doing this on the same night. Each group will then be asked to give 500 miles the money they might have spent had they gone out for that meal in a restaurant or café. That’s all.” She smiles. “I want to raise half a million pounds on that night. We’ll use it for the workshop we’re planning in Zambia.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI look at the ceiling. Half a million pounds. And then I look at Olivia, and I realise that this woman – this remarkable, energetic, inspiring woman – is going to do it. She does it simply because she wants to help those who have suffered what she suffered. It’s that simple.

Is there a religious element to her work? Not particularly, it seems. She believes in the importance of spirituality, but she does not wear that on her sleeve. This is all very practical – very down to earth and immediate. This is about changing the lives of more than 100 people every month. This is about doing that from a small office in a house in Edinburgh.

People seem willing to assist Olivia. The former first minister Jack McConnell has been particularly helpful, as he has been to a number of causes in Malawi. Then there has been help from The Proclaimers, the musicians whose 500 Miles finds its echo in the charity’s name. Olivia has new words for that song, and she shows them to me. Imagine them being sung to the tune of that irresistibly catchy song:

In Malawi, there’s a boy who’ll sit and cry

Who’ll sit and cry because he can’t walk down the street,

And I say “Are we gonna walk on by

Or are we going to get him on his feet?”

And I would walk 500 miles,

And he would walk 500 too…

My hour with Olivia is up. We go downstairs. Outside, it is still blustery, but clear. The sun that shines on us is the same sun that shines on those people in Malawi, our brothers and sisters. Olivia drives herself. Her white car is parked in the street. She goes off. I go back to my study. I have other visitors to speak to, but I think for a few moments about what I have just seen and heard and of the warmth of the whole story. It is like standing in the sun.