Paul Bradshaw: Background crucial factor in child development

How successfully children, learn, remember, problem-solve, and learn to speak are important indicators of their development in the early years and strong predictors of how they will fair at school and even beyond, in further or higher education and the world of work. Together these aspects of children’s learning are known as their cognitive development.

For the last ten years ScotCen Social Research has been running the Growing up in Scotland study (GUS), a survey-led project which follows the lives of two groups of Scottish children: the first born in 2005 and the second in 2011. In total around 10,000 families are involved.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUsing the study we’re able to monitor how well children are developing and identify where and why differences occur between children from different backgrounds. Monitoring children’s cognitive development is crucial because it’s such an important predictor of later outcomes at school and beyond. It’s also possible and more straightforward to address language delay when children are younger than it is when children are older, and improvements at young age are likely to lead to improved outcomes later.

Signs that some children are likely to do better than others as result of the environment they grow up in are a concern for parents and policy-makers. They’re indicative of social inequality and show that efforts to offer all children the best start in life aren’t yet fully addressing the disadvantage many children face because of the socio-economic characteristics of their parents. Nevertheless, collecting data to better understand and address this disadvantage is an important step.

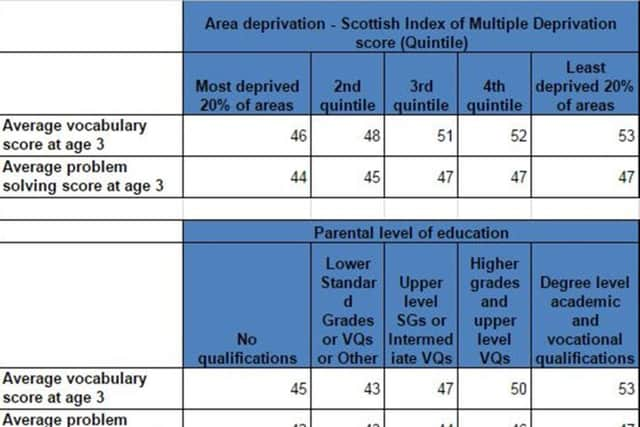

GUS can examine inequality using a range of indicators such as area deprivation, parental level of education or household income. For example, data from the study’s group of children born in 2010 shows that at age three children in Scotland living in the least deprived areas had higher average cognitive ability scores than those living in most deprived areas for both vocabulary and problem solving. On average, children from the least deprived areas scored 53 for vocabulary and 47 for problem solving compared with 46 and 44 respectively for children from the most deprived areas. The average scores for all three year olds were 50 for vocabulary and 46 for problem solving.

Parental educational backgrounds are particularly differentiating on these measures. Again looking at scores at age three, children whose parents had no formal qualifications scored 45 on average when tested on their vocabulary development, compared with an average of 53 amongst children whose parents had degrees.

Household income is also related to children’s vocabulary and problem solving ability. Three year olds from the lowest income households scored lower on vocabulary and problem solving than those in the highest income households - average scores of 48 and 53 respectively for vocabulary and 44 and 48 for problem solving.

These inequalities are stark and data from Growing up in Scotland is helping policymakers understand what might be done to address them. For example, the study has shown that activities such as being read to every day at 10 months and being actively involved in daily home learning activities (such as singing nursery rhymes or painting and drawing at 22 months) are significantly related to better vocabulary ability at age three even after taking account of socio-economic backgrounds.

These kinds of home learning activities, which have little to no monetary cost, can moderate the effects of socio-economic background and help improve the early outcomes of those most disadvantaged – setting them up for better outcomes in later life. Thus better supporting parents with more informed policy making using findings such as those from GUS will no doubt lead to positive changes.

Paul Bradshaw is a Group Head at ScotCen Social Research and Project Director of the Growing Up in Scotland study. His primary research focus lies mainly in the areas of families, children and young people.