Education Scotland: Are Scottish schools falling behind the rest of the world after reforms stalled again?

Many were disappointed but few were shocked by Jenny Gilruth’s announcement this week that decisions and debates on an overhaul on Scottish school qualifications would be pushed back until next year.

Indeed, some academics and influential teaching figures have been privately predicting for months that proposals tabled by Professor Louise Hayward to reduce the number of exams faced by pupils, and to introduce a new Scottish Diploma of Achievement, would never progress.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Gilruth’s announcement on Tuesday followed a previous statement by the education secretary in June which delayed legislation for replacing the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) and Education Scotland (ES).

“It reinforces the impression I had before the announcement that there was an inclination to delay big decisions,” said Professor Walter Humes, offering his reaction in evidence to MSPs on Holyrood’s education committee on Wednesday.

The Stirling University honorary professor had earlier noted that there “seems to have been a bit of a loss of nerve” around the replacement of SQA and ES, with the process having “slowed down a bit” due, he suspected, to the legislative programme and cost concerns.

For her part, Ms Gilruth, who ordered a review of all aspects of education reform after taking the job in March, has “categorically” denied that money is a factor.

“My officials would have been much happier, I have to say, if we had just gone ahead – because the legislation is sitting there, good to go,” she told The Scotsman in August.

“But that is not where the profession is, and it’s not where the kids are either, and I just in all of this come back to the children and young people that we are meant to be improving this system for.”

Whatever the explanation for the ongoing delays to both structural reform and revamped qualifications, it leaves Scottish education in limbo.

Even before Tuesday’s statement, the Association of Directors of Education in Scotland (Ades) was warning that the entire system had been “paralysed” as a result of the publication of multiple reports containing scores of recommendations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Scottish Government commissioned the OECD in 2019 to carry out a review of Scottish education, but that process itself was delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, exams were cancelled and the SQA was heavily criticised for its mishandling of an alternative grading model, which led to another Government-commissioned review.

The OECD finally reported in 2021, suggesting a refresh of Curriculum for Excellence, particularly in the senior phase, prompting the Scottish Government to announce that the SQA would be scrapped, with Professor Ken Muir commissioned to review the plans.

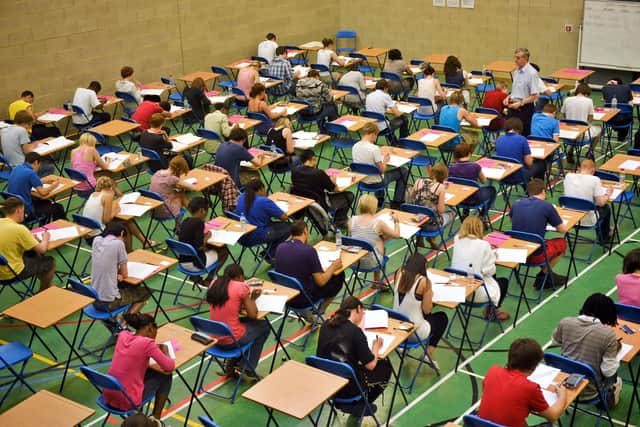

In the meantime, Professor Gordon Stobart, who was appointed by the OECD in the wake of the exams fiasco, presented his recommendations for the qualifications system, warning that Scottish pupils were amongst the most heavily examined in the world.

Prof Muir reported last year, recommending a “national discussion” be held on the future of Scottish education, which in turn reported in May this year, after gathering the views of 38,000 people.

The following month, Prof Hayward reported her recommendations on a shake-up of the qualifications model.

Meanwhile, James Withers’ report on the skills landscape was also published in June, recommending the creation of a new body to replace Skills Development Scotland, the Scottish Funding Council and, possibly, the Student Awards Agency Scotland.

On Tuesday, as she published a new report by the First Minister’s International Council of Education Advisers, Ms Gilruth admitted she had not yet been able to “knit together a narrative linking” the “plethora of different reports” she had on her desk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut one of the authors of those reports, Professor Stobart of University College London, had a warning about delays to qualifications reform.

“The rest of the world is getting on with this kind of thing,” he told the education committee.

“There are reforms going on everywhere. Even the French Baccalaureate is being reformed, and that takes some doing. And New Zealand and other countries are all looking at ways of bringing their assessment system and the curriculum up to date.

“If there is this ongoing internal debate in Scotland but no movement, dare I say, don’t be surprised if you find others have gone past you.”

His remarks were supported by Dr Janet Brown, convenor of the education committee at the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

“If we don’t do something, we will fall behind. I think it is really, really critical that we think it through, but Scotland will never, ever reach consensus on its qualifications structure.

“I just think we need to accept that, and somebody needs to take a decision, and take the leadership, and do something.”

In France, after a four-year period of reform that was interrupted by the pandemic, the baccalaureate is now 40 per cent determined by continuous assessment, and 60 per cent exams. Grades were previously 100 per cent based on exam results.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn England, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak wants to replace both A-levels and the Government’s new T-levels with a baccalaureate-style qualification called the Advanced British Standard.

Meanwhile, a review carried out for the Labour Party, recommended a “reformed, creative and forward looking curriculum”, with “multimodal” assessment so progress is no longer just measured through written exams.

Lindsay Paterson, emeritus professor of education policy at Edinburgh University, said that Scotland’s assessment system does “urgently need reform”.

He said current exams encourage the “worst kind of rote-learning”, while assessed coursework is “unfair to students who can’t access support at home”, and the cramming of National courses into too short a period of time has narrowed the curriculum.

But he added: “One major reason for the impasse on how to reform is the poor quality of the recent reports on these problems – from the OECD, Gordon Stobart, and Louise Hayward.

“These have been ill-informed, badly argued, and cursed by an indefensible hostility to exams. Abolishing exams would widen inequality and weaken rigour.”

Prof Paterson is not alone in expressing alarm about the plans.

SQA chief executive Fiona Robertson has highlighted “workload implications”, as well as concerns about the “validity, reliability, practicability and fairness” of the move away from exams.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf Paterson said doing nothing was “not an option”, however.

He suggested smaller steps such as improving the exams to discourage rote learning (memorising information by repetition), as well as reducing the pressure of time in the syllabuses so that assessed course work is done under the supervision of teachers, not at home, and for all schools to start all National courses in third year to give space for breadth and depth of learning.

"These modest reforms would deal with the worst problems,” he said.

Graham Hutton, a former head teacher and now general secretary of School Leaders Scotland (SLS), said the vast majority of senior teachers in secondary schools were in favour of progressing the Hayward blueprint, however.

“We think this is a golden opportunity to move Scotland’s education system forward,” he said.

“I think we’re at a major cross-roads and I suppose, like the proverbial learners that we have got in school as they enter the senior phase, we have got to consider what pathway we are going to go down that will lead to a better future.”

He added: “There is a lot to be gained from the Hayward proposals, in all schools, but particularly in schools in a higher deprivation area.

"By changing the assessment system you will make it more relevant and interesting and enjoyable for young people, and they will then better fulfil their outcomes. We think they are really well argued proposals.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack at the committee, Prof Humes said the only way to successfully implement reform would be to win the “hearts and minds” of teachers, learning from mistakes made during the introduction of Curriculum of Excellence, and addressing a longer term “loss of trust” in decision-makers and their policies.

Ms Gilruth, a former teacher, has already signalled that she hopes to regain that trust, and has made a point of attempting to involve teachers in the progression of policies.

She clearly suggested her decision on Tuesday had been influenced by feedback she had received from the profession, including a survey of more than 2,000 lecturers and teachers.

The education secretary had found there were “varying views on next steps”, and on the “perceived appetite for radical reform”.

At a time when schools are dealing with post-pandemic problems relating to attendance and behaviour, Ms Gilruth said: “For every ardent supporter of radical reform tomorrow, there are ten teachers telling me about the other challenges they face at the chalkface.”

This claim seems to have now been undermined by Scotland’s largest teaching union, the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS).

Asked if the EIS agreed with the claim that Scotland risked falling behind the rest of the world, general secretary Andrea Bradley told Scotland on Sunday: “We are already behind.

“Other countries have already reformed their assessment models and created a more level playing field by reducing the amount of high stakes, exam-based assessment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If the Scottish Government does not grasp the opportunity to move forward now, it will not only fall further behind internationally, its inaction will amount to an unforgivable betrayal of the electorate, and of the young people whose life chances continue to be negatively impacted by the inherent inequalities baked into the current model of senior phase assessment that affords the greatest status to high-stakes exam-based assessment and is of greatest benefit to the most affluent young people in our society.”

Of course, inertia is nothing new in Scottish education, which is why few would have been surprised by Ms Gilruth’s statement on Tuesday.

For Prof Humes, it comes back to problems which are wider than the structures the Government is supposed to be reforming.

“In some ways, Scottish education is trapped in its own bureaucracy,” he told the education committee.

“There are just so many agencies with so many people, meeting again and again in different arenas, revisiting the same issues and coming to no very firm conclusion.

“The real problems of Scottish education are cultural rather than structural. They are to do with power and the capacity of key players to defend their interests, their territories, and stop things happening.”He added: “For cultural change to happen it has to start at the top. It has to start in the way that politicians, national and local, operate.

“It must involve the chief executives of national agencies, inspectors, directors of education and senior civil servants.

“And that is the challenge I think that faces your committee and indeed Scottish education generally.”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.