Interview: Ross McEwan

“Look, call me old fashioned,” he says, when the conversation turns to recent stories around his dislike of zero interest credit card deals, “but I like people paying back. Call me old fashioned,” he repeats, “but I think we should be giving customers a lot more warning about the issues around them,” he says, his New Zealand accent flattening the vowels.

“I’ve never had a problem with borrowing money myself but I like to get it paid back. I’ve been lucky enough probably all of my life, if I put money on a credit card I pay it off in the month. I’m a bank’s worst nightmare. And I think that came from my mother.” He laughs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcEwan’s attitude to money was formed back in NZ, where his mother was a shop assistant and bequeathed him her financial mantra.

“‘It’s not how much money you have, it’s what you do with it’ she used to say. We wanted for nothing,” he says, “but she was frugal. Even on a pension she would save and ask me what she should do with it. I would say, ‘mum, why don’t you think about spending it?, but she wanted to save it.’

His dad, an Australian who started in banking then joined the air force before flying crop spraying planes, added to his money make up.

“I remember I borrowed some money off my dad and him saying ‘I want it back’ and it’s something I hope I’ve instilled in my children. If they borrow money, they’ve got to pay it back. They got pocket money but had to do things for it, and now both of them are working and able to save.

“My daughter started her business from zero – yes, I helped her get that up and she’s paying me back. I want her to, not because it’s important to get the money back, but it’s important she learns the value of money.”

And does he get dad’s rates for his tea and scone at her cafe in London?

“No! I pay full price. The staff say to me do you get the staff rate, and I say no, dad pays the full price.” He laughs.

“I’ve learnt a lot watching the pain and anguish that goes into building a business. Same with our other daughter, I can help with money, but it’s nice to see them paying it back.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcEwan is approachable, but isn’t afraid to say no when it’s required.

“I think that’s something we as banks forgot to do and why we ended up in crisis. Tell people why, but if the right answer is no, that’s the answer.”

As for zero interest credit deals, he wants more information about the charges, penalties and rate hikes. “With these products, around 50 per cent of people get to the end of the time and roll again. And when the rate changes, 60 per cent don’t even know what it’s going to change to. To me that’s fundamentally wrong.”

He’s similarly phlegmatic on the subject of compensation for victims of fraud and happy to have started a debate with his comments.

“Look, if people hand over their passwords, should the bank be accountable? I don’t think so. We take care of vulnerable customers and put measures in place – we’ve a new tool that can detect if it’s you using your device – and need customers to take responsibility too. If someone hands over their card in a bar and all their mates buy drinks on it, should the bank have to pay for that?” He laughs. “I wouldn’t have thought so.”

Maybe customers are forced online by closures I suggest, but McEwan is adamant they are voting with their fingers and choosing digital.

So who is Ross Maxwell McEwan, the straight-talking Kiwi who took on the job of restoring the 290-year-old bank’s reputation when he stepped into the CEO chair in 2013? What kind of person wants to take on customer and shareholder ire after the Fred Goodwin years and the bank’s part in the financial crisis of 2008, to be accountable for the subsequent £45bn government bailout?

Born in New Zealand 60 years ago – “my dad’s family was from County Clare in Ireland, part of a clan pushed out of Scotland about 500 years ago. His family went to Australia, then dad moved to New Zealand” – McEwan is based in London with his wife Stephanie and two grown up daughters, but “up here all the time”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

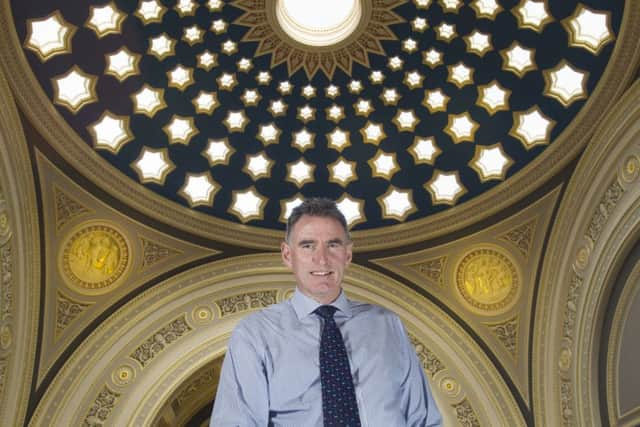

Hide AdTall and rangy, with short dark hair, he’s business smart in dark blue suit, striped blue and white shirt. His blue tie has tiny flashes of colour, but it’s discreet and a smartwatch is a reminder of the bank’s digital direction. He’s every inch the respectable banker, warm courteous and polite as he shows us around the recently refurbished building, the banking hall with its beautiful star studded dome, the offices and boardroom. He points out the portrait of John Campbell, cashier during the 1745 Jacobite rising that hangs on one wall. More flamboyant than today’s chief banker, Campbell is resplendent in a black and red kilt.

“There he is in his tartan,” says McEwan. “Of course he shouldn’t be wearing that because it was banned at the time” he says, and laughs.

Part of McEwan’s job is to rehabilitate the bank, rebranding as the Royal Bank of Scotland once more and pushing RBS, the investor brand, out of focus. Keen to stress the bank’s profile in the community, there’s a Money Sense programme in schools and this summer he’s been out and about chairing an Edinburgh International Book Festival Q&A event with Crash Bang Wallop author Iain Martin. Come December he’ll be jumping in a sleeping bag in Edinburgh’s Princes Street Gardens for Sleep in the Park alongside Bob “give us the money” Geldof, other business leaders and 9,000 others bidding to raise £4m to fight homelessness in Scotland.

“Banks have a special place in society and it’s why people got very upset about us losing that safe and secure position we should have in the market place. Businesses should be good citizens, but we have an additional responsibility because of that fundamental role of lending into communities,” he says.

But why would anyone want to take on such a job, given the bank’s low reputation after the financial crash?

“Look, this is one of the iconic jobs in banking. This was a bank that was doing great things worldwide and all of a sudden it was on its knees. I thought we could repair it and more importantly put the pride back. That’s pride in our colleagues, in customers, and our shareholders, which is the UK public who were quite rightly scornful about this bank, having to put in £45bn of public money.

“There was hubris and now I think there’s a humbleness. We’re here to serve customers and make money long-term for shareholders by looking after customers.”

McEwan is optimistic, with the bank – Scotland’s largest private sector employer with 10,500 of 92,400 staff based here – reporting an operating profit for the second quarter of this year of £1.2bn compared to a £695m loss in the same quarter of 2016, a 24 per cent rise in income and 32 per cent fall in operating costs compared to the previous year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet the legacy of the past persists when it comes to passing stress tests and the prospect of returning to an overall profit. Then there’s the question of a return to private ownership.

“If we resolve the two outstanding issues – the divestment of some of our SME (small and medium sized enterprise) customer base around Williams & Glyn and the issues around mortgage backed securities that we and others have been fined over – we believe this bank will make money again in 2018. The core bank has been making money, it is restructuring and conduct and litigation that’s been dragging it down. There are two things a financial institution has that it must guard, very, very strongly. The first is financial strength and we lost that – we were broke, so we’ve been rebuilding and are a very strong bank now. The second is reputation, and we damaged that very, very badly. I think the repair job is going to take some years. We’re getting better but we still have a long way to go.”

So how did he set about turning round the bank’s reputation?

“We had really good positions in the UK and Republic of Ireland to serve customers long term and make money, so we brought the bank back from 38 countries down to 14, re-shaped and got rid of assets and products that didn’t make sense for us. We’ve dealt with most of the legacy issues and are in better shape, but reputations are not rebuilt in a year and this bank did very severe damage to its reputation. We were seen as the bank that brought down the UK economy, along with others, but we were a big part. We had focused on growth as our prime driver instead of customers. The UK taxpayer ended up saving this bank so we had to re-focus onto customers and rebuild.

Another concern for McEwan right now is Brexit, which he approaches from a customer point of view.

“How do we keep them able to trade so we don’t have a big drop-off in productivity and business in the UK? We will look after customers. We’ve got a bank licence in Amsterdam we can purpose easily and have a European entity with about 150 staff, although our HQ will be in the UK.

As for a possible indyref2, his approach is similarly pragmatic.

“Oh, I’ll leave that for the Scots to work out for themselves,“ he says. “Yeah, I don’t get a vote. For the bank, we wouldn’t operate any differently. We’d take the plaque to England, the reason being this bank is just too big for the Scottish economy to have reliant on it if something goes wrong. We’ve got a very large Scottish business – 1.7 million personal customers, 140,000 business and commercial customers, 27,000 charities and about 30,000 private banking customers – and we’ll be here to look after them. We will look after the Scottish people in or out of an independence arrangement.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcEwan prides himself on changing a culture that “lacked openness” to one where staff and customers can ask whatever they like.

So in that spirit, does he think he’s worth a pay packet that was reported as around £3m last year?

“I think it comes round to what the market pays for a skill anywhere. You’re going to be paying for a resource of any sort, and I am a very well-paid executive. I don’t think there’s any other answer to that.”

As for whether this insulates him from the financial realities the rest of us struggle with he says, “You know, most of my friends do not earn anywhere near what I earn. My family do not earn what I earn. And I go back to it’s not what you get paid so much as what you do with it. I have seen wealthy people end up with nothing and those who have earned a basic wage ending up reasonably well off.”

So rather than buy a house back in New Zealand to return to one day, McEwan and his wife have invested in a cattle farm near Auckland.

“I’m not a farmer,” he says, “but wanted to put money into something that will grow, to see good people grow a business. To see productivity going up and people growing themselves, that’s interesting for us.”

McEwan has always professed to be a people rather than numbers man, so is it true that he failed accountancy level two while studying for his business studies degree?

“Yes, I did.” He laughs and takes a long sip of his tea. “It’s not something someone who is running a bank should be proud of, but in my first year I passed all papers plus an additional one so there was a little bit of a slack in the second year, which flowed into the third year… And I’m reasonably good with figures – I can see important trends as opposed to wanting to be an accountant, and a business is about people.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But to me university’s a great experience and you develop as an individual. It was also where I met my wife, so it was a good place to be. She was in the women’s basketball team and I was in the men’s, so we did a lot of travelling and it was a lot of fun.”

Stephanie went on to graduate in food management and today works with their daughter in her cafe.

After graduation McEwan worked his way up at Unilever, Dunlop and National Mutual and by 40 was NZ chief executive for Axa. First NZ Capital Securities and the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, followed then he joined RBS in 2012 to head their retail banking.

He’s used to responsibility but what wakes him in the middle of the night?

“Things like fraud, money laundering, cyber attacks, keeping the bank safe. Or an outage like 2012 which I wouldn’t say could never happen again, but we’re prepared for with better technology and support.

“I’m reasonably relaxed, but any CEO, if you don’t get stressed, you’re not thinking about it hard enough. I always have my phone with me. But weekends are important to us and we do things we enjoy like cycling and sport, going to a movie. You need to decompress mentally and often I find solutions when I’m out cycling.”

McEwan’s name has recently been linked to the top job back at the Commonwealth Bank of Australia but when we met McEwan wasn’t talking about any moves.

“I’m here while the board wants me. I want to see the bank on a really strong path to focus on customers and making money and starting the government out process. That would be important for me. I’d love to see the Scottish people really proud of this bank again, because it’s their bank and the UK public saved it. The biggest reward for them is to have a good bank back.” n