Works that altered the course of Scots art

Now the series ends with JD Fergusson at the SNGMA.

It is a beautiful exhibition. Thoughtfully selected and arranged for maximum impact, it makes a fitting climax to the series. But it also shows how much Fergusson came to stand apart from the other three. He and Peploe were close friends.

Early on they often worked side by side, and at this time Fergusson painted vivid, small landscapes and gorgeously fluent still-lifes inspired by Manet and perhaps too by Peploe. There is a fine selection here and if he had painted nothing else he would still qualify as one of the Colourists.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut he was more ambitious than that. He wanted to be a real modern artist, and in 1907 he settled in Paris where it was all happening. Fergusson, started to paint really big pictures after his move to Paris, and this is where the exhibition takes off.

These pictures are really shown to advantage and reveal how different he became, not just from the other Colourists, but from any contemporary British artist. In Paris, too, he started to paint people, women especially. Although he still painted landscapes and also magnificent still-lifes such as The Blue Lamp, his focus had changed.

The show traces how the shift began with a range of vivid drawings, often almost caricatures, of life in the streets and cafes of Paris. It was the time when the fashion was for women to wear enormous, elaborate hats. In photographs they look too much, but Fergusson loved them and paintings here such as The Hat With The Pink Scarf bring out their stylishness and dramatic allure. He also painted women in glamorous, full-length portraits, as in the Red Shawl and Le Manteau Chinois, but he began to experiment with radical new ideas. La Force, a picture of a naked woman from about 1910, has an expressionist urgency in the way it is painted that makes the nude really confrontational.

Rhythm and From My Studio Window are from the same time as La Force and are also female nudes, but they are more structured and less impulsive. They are also very big, and hung side by side on a wide empty wall they look very powerful here. They were painted at the time that Picasso and Braque had started the Cubist revolution. Clearly Fergusson understood what they were doing, but he made it his own. You cannot say that of any other British artist.

In From My Studio Window, the naked woman, the fluttering curtains and landscape intersect each other in a way that reflects the new visual language. But there is something else at work here too. The woman herself has a face like a mask, as though she represents some primitive life force surging through the picture. In Rhythm this idea is personified in a seated woman with a magnificent, heroic build. She has an apple in her hand as though she is a modernist Eve. If she is, then Les Eus, Fergusson’s extraordinary painting which has a wall to itself, represents a modernist Eden. It shows six, life-size figures dancing naked beneath branches laden with fruit.

In 1913, Fergusson met the dancer Margaret Morris – his lifelong partner – and he often drew and painted her. Briefly in the south of France they tried to live the hedonistic life of Les Eus, but the First World War intervened and they returned to London. Fergusson began to make sculpture, and there is a bigger and better display here than I have ever seen before. It shows he was a serious modern sculptor.

Advertisement

Hide AdFergusson also had ambitions to be a war artist, no doubt partly because he needed the money. This was not to be, but he did spend a very fruitful period working in the docks at Portsmouth. Four of the remarkable paintings that resulted are hung here together, perhaps for the first time. Nearby another group of four pictures hung together still make an impact now as they did when they were first shown in Edinburgh in 1923.

These are Fergusson’s Highland landscapes. Cubism comes to the Highlands: these dramatic pictures directly influenced the subsequent course of Scottish painting.

Advertisement

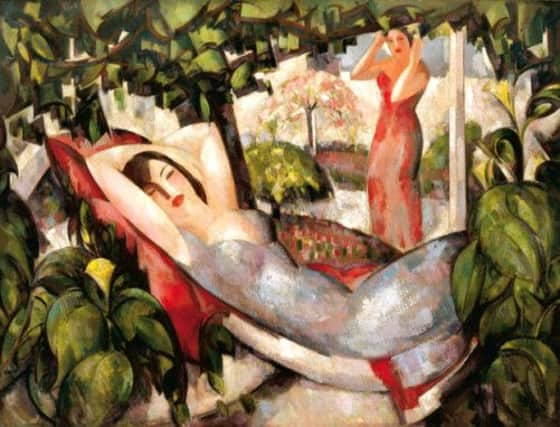

Hide AdAfter this, the last room in the show of Fergusson’s later work is not exactly a letdown, but it does suggest that the Highland landscapes marked the end of his really creative period. Pictures painted in the 1930s such as Megalithic, or Summer 1914 – the latter a painted memory showing Morris lying blissfully idle in a hammock in Antibes 20 years before – are impressive. The latter picture especially has an elegiac mood. But if his later work has less energy, that doesn’t for a moment diminish the impact of the painting and sculpture that he had done in the first 20 years or so of his remarkable career.

He was a great and very original modernist painter.