When Aberdeen shocked with its soft touch to piracy

It may have been a small city in the 14th and 15th Century but Aberdeen was capable of some big upsets on the European stage due to its soft touch approach to piracy, it has emerged.

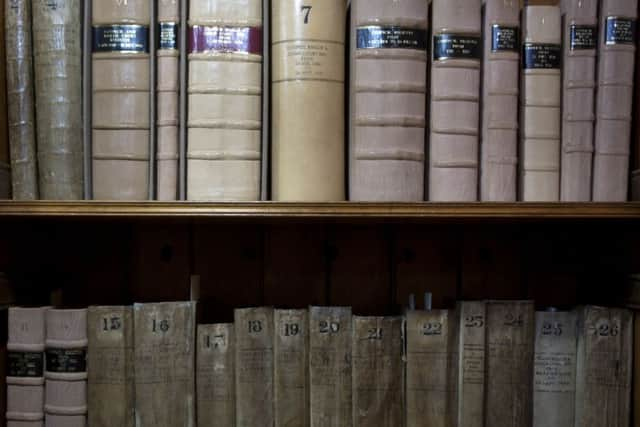

Academics at Aberdeen University have studied Scotland’s oldest civic records - the city’s burgh records of 1317 - and analysed court rolls and council registers to determine Aberdeen’s rise into an important trading partner.

Advertisement

Hide AdThey have found that the reputation of Aberdeen, where just a few thousand people lived at the time, had a reputation marred by disputes over the city’s perceived leniency towards piracy, which extended up the social scale and even included its fifteenth-century Provost.

Dr Jackson Armstrong and Dr Andrew Mackillop from the University of Aberdeen led the study, funded by the Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies.

Dr Armstrong said: “The Aberdeen Burgh Records are the earliest and most complete body of surviving records of any Scottish town. They contain court documents from as early as 1317, during the reign of King Robert the Bruce, and are then a complete record from 1398 to the present day with the exception of one missing volume.

“They are a unique asset providing a great insight into medieval life in Scotland and particularly in Aberdeen. They show that the city ‘outperformed’ on the European stage in terms of its size and that it was recognised by Bruges – one of northern Europe’s foremost medieval cities – not only as a significant trading hub but as one of the ‘great towns’ of Scotland.

“From the records we can see that in August 1465 alone six ships from Flanders and the Netherlands arrived at Aberdeen. They carried a variety of goods, including cloth and salt.

“There is also evidence of high status goods including walnuts, raisins, figs, and pepper arriving in Aberdeen from the Continent which demonstrate the extent of trading in this period.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“However, the records also show that relations were not always good and were often marred by disputes around piracy, with Aberdeen perceived as ‘turning a blind eye’.”

Dr Edda Frankot, the project’s research fellow, and author ‘Of Laws of Ships and Shipmen’: Medieval Maritime Law and its Practice in Urban Northern Europe (2012), said many examples of a lenient approach to piracy can be found in the records.

Advertisement

Hide AdShe suggests the issue may have been greater in Aberdeen because shipwrecks were common due to the difficulties in navigating around a sandbank close to the entrance of the harbour.

“The archives reveal that in 1445 a merchant of Lübeck appealed to Aberdeen’s provost on behalf of the German merchants at Bruges in Flanders. A ship which sailed from Bruges with his cargo had been captured by pirates. It was rumoured its cargo had then been sold in Aberdeen,” Dr Frankot said.

In October 1530, the Jhesus of Danzig was wrecked in bad weather on the coast of the area now known as Cove.

The records reveal that King James V became directly involved when accusations were made that the ship’s cargo had been plundered.

Dr Andrew Simpson, a member of the project team and a lecturer in law at the University of Aberdeen, found that merchants of Danzig - modern day Gdansk - based at the Hanseatic League’s headquarters in London brought legal claims in Aberdeen to recover cloth which was part of the Jhesus’s cargo.

The reputation for a tolerance of piracy even extended to the highest levels of society with Sir Robert Davidson, a 15th Century provost and wine merchant, said to have condoned the thievery on the high sees.

He had close working links with the admiral of Scotland, Alexander Stewart, the Earl of Mar, at the time.