War Horse author Michael Morpurgo on his influences

WHEN he was 19, writer Michael Morpurgo was sitting with his mother watching Great Expectations on the TV when she turned to him and told him the man playing Magwitch was his father. Until then, young Michael had taken it for granted that the man married to his mother was his dad. However, it turned out that when Kippe Cammaerts was a young actress she had been married before, to the actor Tony Van Bridge, and the couple had Michael and his older brother Pieter. While Van Bridge was away during the Second World War, she met Jack Morpurgo, whom she later married. Van Bridge emigrated to Canada.

“She was appalled that he had suddenly appeared on TV after all these years of people not talking about him. In those days, if there was a divorce you didn’t talk about it. I had been brought up by my stepfather, and I simply accepted the fact that we didn’t talk about it. It’s very easy to condemn, but marriages broke up because of the war, things were breaking down. It was down to Hitler, and Mum and Dad split up,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“But it turned out we had this father out in Canada. Later, when I was in my mid-sixties, I went over there to see him in a play, aged 84. It made me terribly proud. The theatre was full of older ladies who were his groupies, and at some point I turned round and said, ‘That’s my dad’.”

That he had been unaware of his parentage and that it was never discussed, although there was contact when Morpurgo reached adulthood, says a lot about his stiff-upper-lip post-war upbringing. It also explains why he might have a penchant for treading the boards, albeit in a very modest way. Take a close look at the supporting cast when the stage version of his best-selling novel War Horse comes to Edinburgh in January.

“I often go and meet the cast and tell them about writing the book. If I get on well with them, they say, ‘You must come and act on the stage.’ I’m in the crowd, where you can lose people that can’t act. They dress me up, usually like a Devon squire for the market scene where I bid for the horse and I come in at the end. I get a sense of belonging and I love the camaraderie of the theatre, being involved in storytelling. Mum was an actor and so was Dad, and just to be part of it is wonderful. It’s powerful. I can say to my grandchildren, ‘I have acted on Broadway and the West End,’ and I get bits of costume to keep. I have a suit from Broadway, shoes from Toronto … I’m going to Edinburgh, so who knows …”

Morpurgo, now aged 70, is gentle and polite and has an avuncular manner that delights in telling a story. He’s had plenty of practice, with 120 books to his name since he started writing in 1974. There can’t be a schoolchild in the country who hasn’t read or listened to one of his tales, often featuring animals, and he has won the Smarties Prize, the Whitbread Award and the Blue Peter Book Award, and was Children’s Laureate from 2003-2005. His classroom classics include Kensuke’s Kingdom, Why The Whales Came, Little Foxes and the best known, War Horse, the National Theatre version of which has been seen by more than four million people since its premiere in 2007.

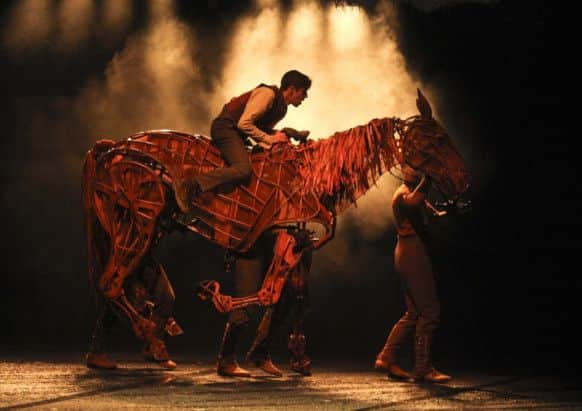

The story of one of the one million horses taken to Europe by the British Army in the First World War, War Horse is told from the neutral point of view of Joey, who goes to the front as a cavalry horse, is captured by the Germans and is used to pull ambulances and guns. The National Theatre production won rave reviews for its ground-breaking puppetry as well as a Tony for its Broadway run, and the tale was given fresh legs when another great storyteller, Steven Spielberg, turned it into a Golden Globe/Oscar-nominated film in 2011, which in turn pushed the book on to the bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic.

“I never thought about it being a film when I was writing it. That was only afterwards, when it became a fantasy that someone would come along and make a film of your book. When the phone rang, my family used to joke that I should answer it in case it was Spielberg. And one day it was. Well, his publicist. He has great vision and there are many things I love about the film, but for me the play’s the thing. That has real power right the way through – 36 people working their socks off in a carefully woven patchwork, live, and that’s completely convincing.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“War Horse works because it’s about things so many people long for: peace and reconciliation, and living in hope through the ghastliness of war. People want to believe the stories they love, so will believe in the puppets. It’s important that you’re not somehow moving away from it because it’s for kids, or it’s told by a horse. You want grown-up people to see it too and the theatre production has broken through that,” he says. “I write for everyone.”

This is true. Looking around the War Horse audience, when I saw the play in London, there were more adults than children, suspending disbelief as the horse’s three-person puppet team led them through the drama and became almost invisible. They gasped when Joey was caught on the barbed wire of the battlefield and sniffed into their man-sized at the denouement. After the show, when I was lucky enough to meet Joey himself, despite the fact that his three puppeteers were standing next to me, two of them still in harness, it proved impossible not to reach up and rub his nose.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I’m a father and a grandfather. My three children are aged from 49 to 52, and my grandchildren from seven to 26. I’ve been with children all my life and I know they have insight and clarity. They can deal with grief and schism inside families, and with war. They know about sadness and you can communicate to them difficult subjects to do with human existence.

“When I first heard that they were going to make my story a bunch of puppets on a stage, I had no faith at all. Well, you wouldn’t, would you? I mean puppets and the war? The director said you can’t have talking horses, it would be absurd. So they made a puppet, which is even more absurd. But you believe it. It works.”

War is a theme close to Morpurgo’s heart. He was a war baby, born in 1943 and with the devastation of the Second World War looming large over his childhood – his mother’s brother Pieter, an RAF pilot, was shot down in 1940, and Morpurgo grew up playing in the bomb sites of post-war London. Respite came, however, when he was sent away to boarding school, in Devon and later in Canterbury, where he survived by being good at sport and marching up and down the parade ground in the school’s cadet corps.

“I was away at school from a very early age and grew up fairly fast in terms of being able to survive, but less fast emotionally. There was a sense of ‘we are all in this together’, nothing was that terrible. You could ignore the cold dormitories and occasional beatings because it happened to us all,” he says.

“What I did feel when I left school was supremely confident. You have the gift of the gab, you feel you can do anything. You learn quickly that you can’t. That kind of confidence can tip over into arrogance and not wanting to empathise. I got lucky and met the right person and got drawn back from the brink.”

The right person was Clare, the daughter of Penguin publisher Sir Allen Lane, whom he married at 19.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“She has been my right hand all my life … my reviewer and editor too.”

Following boarding school, Sandhurst seemed a natural progression for Morpurgo, but after 24 hours there, he realised “playing at war” wasn’t for him. Clare agreed. Instead, he headed for university, where he gained a third class degree in English and French from King’s College London.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I was hopeless and got the poorest degree ever awarded by London University. Later the vice chair wrote to me and said, ‘We want to give you a doctorate,’ [one of 11 he has been awarded] and I wrote back and said, ‘That’s fine, but you do realise I got a third,’” he laughs. Then he becomes indignant: “Michael Gove recently said he didn’t want people with third class degrees to be teachers. Philip Pullman has a third too. I say, it’s what you do with it that matters.”

What Morpurgo did was go into teaching, where his story-telling abilities were honed. Every afternoon he’d read the children a story to keep their attention, and when the books ran out, he began to make them up with even greater success.

“One of the things I have always loved is the silence that you can create when people are focused as they have never been before. The silence in a classroom is the best thing you can create when you’re all so wrapped up in a story, 35 children all with you. You hope it gives them the idea that they too can tell stories,” he says.

“I only came into the joy of writing through the power of stories. We stop far too early reading stories; grown-up people love having stories read to them. Parents become children,” he says.

If teaching set Morpurgo on the path to writing, his career was further fuelled when Clare led him to Devon, where she had spent her childhood summers, to set up the Farms for City Children charity in 1975. Thousands of children have taken part in the scheme, and in 1999 the couple were awarded MBEs in recognition of these services to youth, with Morpurgo later elevated to OBE for his services to literature.

“Clare would come down to Iddesleigh and stay with friends at the Duke of York pub in the village and spend her days wandering the lanes and fields of the remote Devon countryside, riding her favourite horse, Captain. It was really her love of this remote and magical place that led us back to Devon in the 1970s to set up the charity where children could come and be the farmers for a week, groom horses, milk cows, and by the end of the week they would grow considerably. We had strong beliefs that a child should grow up with real experience, regardless of schooling, that it’s crucial to your life. In the classroom I couldn’t do that and the very children who needed it most weren’t getting it. That’s why we thought we would invite children who never got a chance to look at a wide sky or scream. Idealistic, but it worked.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I have three of those farms in England now. If someone with a farm in Scotland would like to get in touch, we need a farm with variety, with 300 acres where they can run, and it needs to be 100 miles from a city.”

It was in Devon that Morpurgo hit on the idea of using a horse to tell the story of the futility of war, after meeting an old man sitting by the fire in the pub who told him how he’d been in the First World War. With tears in his eyes, he told of a horse he’d loved and left behind on the battlefields and how it, like the others, had been sold off to French butchers at the end of the war.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Parts of War Horse really happened. There really was a boy from the village who went off to the war and then found his horse and it came back.”

At around the same time, Morpurgo chanced on one of the schoolchildren who had come to stay, a child who had been silenced by a stutter for years, talking freely to one of the horses on the farm.

“He didn’t utter a word to anyone around him and there he was talking to the horse and it was listening, not understanding, but she knew it was important to stand there. She liked the effect and was giving back. I felt there was an extraordinary moment, but not sentimental, and I could write about that.”

Another literary inspiration came out of the Devon connection in the person of Ted Hughes, who turned out to be a near neighbour and would come fishing in the river near Morpurgo’s house. The pair struck up a friendship and the poet became his mentor.

“Ted lived down the road and also brought Seamus Heaney here. To know these great men of literature was wonderful for a young writer; to sit at the feet of such wisdom around the table. He had the power of words, and that’s what I would love to have. The other writer I really admire is Robert Louis Stevenson, for his gift of narrative. He’s the greatest author in the English language, one of those rare writers who does character and dialogue so well. He’s streets ahead of Sir Walter Scott and can do Jekyll And Hyde then do poetry and travel writing too.”

Morpurgo knows the landscape of Stevenson, both literary and actual, intimately. He’s made many trips to Scotland over the years, and has strong views about its connections to its larger, more powerful neighbour.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“My godmother lived in Edinburgh and I used to stay with her and she’d take me all over. She spoke Doric and was very proud of it, and my sister-in-law is Scottish too, so I’ve been to Celtic Connections to hear wonderful music, which is often what survives in conquered nations. We have great debates about the future. I think it’s a retrograde step to be separating into different countries because we live in a world where we should be joining together. If the Scottish-English thing hadn’t been done by conquering and bestiality by the army, then it might not be such an issue to separate.

“If I go up to Edinburgh in two years’ time I’ll feel very different about it if it’s separated. England will be a smaller place without Scotland or Wales or Northern Ireland.”

What would Joey say? If only horses could talk.

The National Theatre production of War Horse is at the Edinburgh Festival Theatre, 22 January to 15 February, tickets from £20-£50 (www.edtheatres.com)