Visual arts review: William Strang | William Morris

Fair Faces and Dark Places: Prints and Drawings by William Strang (1859-1921)

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

****

Anarchy and Beauty: William Morris and His Legacy

National Portrait Gallery, London

****

Really, however, it was just a revival of the market. Whistler, for instance, a leader in this revival, created a mystique around his prints and consequently enjoyed lucrative sales. Others followed him and for a while it was possible for artists like Muirhead Bone or James McBey to make both a reputation and a good living, never dipping a brush in paint, but by their prints alone. DY Cameron, too, is better known as an etcher than as a painter. So too for a while was William Strang, but unlike these other Scottish printmakers, Strang’s prints have fallen out of fashion. Now an exhibition of his work at the NGS drawn from the major collection gifted by his son, David Strang, seeks to put that right and revive the reputation of one of the boldest, most original Scottish printmakers.

Advertisement

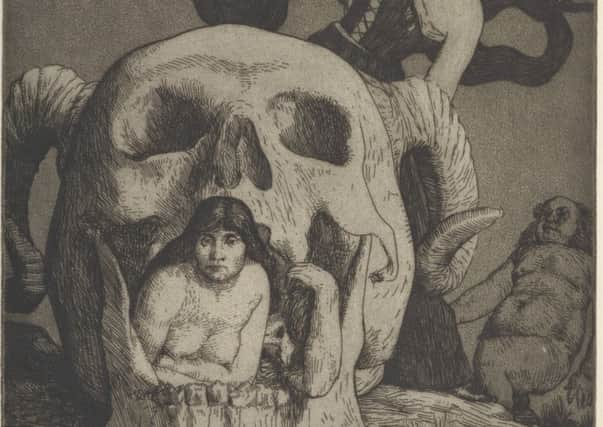

Hide AdBorn in Dumbarton into a family of shipbuilders (they were employees not proprietors), Strang rebelled against life as a clerk in the shipyard of William Denny and Sons. With the financial support of an aunt and advice from an unnamed but clearly enlightened shipbuilder, he went south to study art at the Slade School. There he became a pupil of Alphonse Legros, a French artist who had moved to London and who with Whistler had been one of the leaders of the print revival. Following Legros, for the first 20 years of his career Strang worked almost exclusively as a printmaker. But if beautifully drawn, dramatic views of Venice, of old walled cities in Spain, or of the Scottish Highlands are familiar products of the etching revival, Strang’s work is very different. There are indeed several views of walled Spanish cities in the show, but its title, Fair Faces, Dark Places: Prints and Drawings by William Strang (1859-1922), hints at a very different side to his work, and one far removed from the more familiar products of the followers of Whistler. Grotesque, the signature image for the show, for instance, features a human skull with the horns of a goat and a naked woman emerging from its jaws. Another woman behind is half-undressed, and a figure beyond her seems to be a fat, naked man. Apparently this came to him in a dream. It also recalls some of Goya’s fantastic imagery and Strang recalls Goya even more directly in an illustration to the Earth Fiend, a grim ballad of his own composing, and in an illustration to Without Benefit of Clergy, a story by Rudyard Kipling. In the frontispiece to another of his own ballad compositions, Death and the Ploughman’s Wife, a child is playing football with a human skull.

This dark, fantastic side to his art perhaps partly explains why, while the prints of his contemporaries have never really fallen out of fashion, Strang’s have been neglected. His left-wing views, or at least they way they are reflected in his art, may also have contributed to his falling out of fashion, however. Sometimes, as in The Eating House, where three working men sit in a row at a cafe table, this is no more than a matter of portraying ordinary, unfashionable people with dignity and without condescension in a tradition that goes back to Velazquez. Strang’s political sympathy is more explicit in his print, The Socialists, however. Set in the open in an unspecified urban space, it shows a man standing on a chair addressing a small group of attentive listeners. His flamboyant gestures suggest the passion of his speech; the title its content. Strang himself appears among the audience, making clear where his sympathies lay. Even more outspoken is Despair, a dark and searing image of a woman staring into space in a bare and empty room. She has a child at her breast; another sits beside her, evidently weak with hunger. There is no furniture and the door is falling off its hinges. The receding perspective lines of the floor boards suggest a kind of imprisonment and the artist has emphasised this by scouring lines into the surface of his plate with sandpaper. In its unflinching contemplation of grim social reality, this print, made in 1889, is more like something from Germany 40 years later, by Käthe Kollwitz or Otto Dix perhaps, than a product of cosy, middle-class, Victorian England and in Burning Weeds he makes clear where he stands in relation to the fashionable art of his time. The print is a mezzotint, a method which can create deep, dark shadows. A woman standing in near darkness faces us with smoke from a bonfire rising around her. Her gaunt face and coarse clothes pay homage to the peasants of Francois Millet so much admired by Van Gogh. Strang’s subject and composition also remind us of the other Millais, however, the Pre-Raphaelite then at the height of his fame and prosperity, and in particular his painting, Autumn Leaves, of girls burning leaves in a bonfire in the fading light of an autumn evening. Strang’s picture is a dark and certainly deliberate pun on Millet-Millais and so he condemns the evasion implicit in the stagey prettiness of Millais’ painting.

Strang also made portraits, both as prints and as exquisite drawings, touched with colour in the style of Holbein. Among his sitters were his friends Rudyard Kipling, portrayed in the frontispiece to a collection of his short stories, and Thomas Hardy, with whose novels Strang’s work perhaps has an affinity. Hardy began as a painter and the two men may have met in the Art Workers’ Guild, an organisation founded in 1882 to promote cooperation among artists and the wider social purpose of art. The Guild was one of many enterprises inspired by the ideas of William Morris. Coincidentally, both it and Strang himself feature in Anarchy and Beauty: William Morris and his Legacy at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Strang is represented there by a portrait of CR Ashbee, like Strang himself sometime president of the Guild.

This excellent exhibition explores the work of Morris and his circle, but also the enduring impact of his ideas: if Morris is now best remembered for his wallpaper, that is a grave injustice which the exhibition attempts to remedy. At the root of his thinking was the belief, shared with Ruskin, in the inherent creativity and therefore dignity of labour. Art is not a thing apart, but only the highest expression of this ideal. To allow proper human fulfillment, Morris argued, society needed to be reconstructed from the ground up to provide a more creative way of life for all. Such a society that would also by definition be freer and more equal. This led Morris to champion a wide range of causes from historic buildings to the rights of women and of homosexuals. Design inspired by Morris was integral to the campaigning of the Suffragettes, for instance. Indeed one of the most striking pictures in the show is a vividly animated self-portrait by Sylvia Pankhurst, Emmeline Pankhurst’s daughter. Morris’s indefatigable campaigning for his socialist vision also did much to forge the cross-class alliance that made the Labour Party electable and his example was still there too as an inspiration for the Festival of Britain. In 1951, 99 years after the publication of News from Nowhere, Morris’s Utopian novel set far into the future in 1952, the Festival looked forward to the new Socialist Utopia already promised with the birth of the Welfare State. Strang’s left-wing views so passionately expressed in his prints were not out of step with the times. They were close to some of their most original and enduring ideas.

•William Strang until 15 February 2015; William Morris until 11 January 2015