Visual art reviews: Edinburgh Art Festival

Krijn de Koning: Land

Edinburgh College of Art

Star rating: * * *

Peter Liversidge: Flags for Edinburgh

Various flagpoles, Edinburgh

Star rating: * *

Witches and Wicked Bodies

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Star rating; * * * *

Mostly West: Franz West and Artist Collabor-ations

Inverleith House, Edinburgh

Star rating: * * * *

Fiona Banner: The Vanity Press

Summerhall, Edinburgh

Star rating: * * * *

Among current director Sorcha Carey’s achievements have been a strong public profile, a much clearer attitude to commissioning and a real willingness to play to Edinburgh’s own characteristics, its old and new towns, its dark gothic corners, its hidden spaces and public places.

This year the theme of the festival commissions is Parley: public debate, conversation. Parley is about getting down to business. Often it takes place during a truce between warring factions. At Edinburgh College of Art the neoclassical sculpture court has been transformed into a place of parley by Land, a work by the artist Krijn de Koning, who has been a fellow at the college this last year. With platforms and different levels and little stairs, the structure is that 1970s interior feature, the “conversation pit”, wrought into a sub-Piranesi fantasy in plywood. And it’s a fantasy not least because rather than being empty, the place is populated by selected highlights of the College’s historic cast collection, each placed on the ground and peeking up through the new floorboards.

Advertisement

Hide AdThus you may debate the finer points of participatory art practice while staring at the nude bottom of a flayed man, the Ecorche of Houdon. Or think about conflict resolution while staring down St George in full armour. The idea of course is getting history and grand ideas off their pedestal. Even the Victory of Samothrace can look pretty shoddy in a dust copy viewed close up. Whether it will be a place of transformation or a parliament of fools may depend on the quality of the art festival debates and discussions that will take place there.

It’s not an original idea, Tatsuoro Bashi did things better at the Liverpool Biennial a decade ago, building a whole hotel room around a public statue of Queen Victoria, but it’s a smart use of a complicated space and a simple and effective replacement for the previous idea of a Festival annual pavilion, which had always seemed a bit of an EAF vanity project.

At sea, parties about to parley would raise a black flag, calling a truce. Peter Liversidge is flying the flag of parley for the festival, a white flag bearing the single word: Hello. In an attempt, perhaps, to shake off the city’s reputation for a certain froideur, the artist has persuaded some 50 institutions to take part in the Flags for Edinburgh project. It’s a project perhaps more interesting on paper than in practice. The institutions that have said yes, from the Canongate Kirk to West Register House, are less fascinating than those who felt they were bound by rigid protocol to say no, including the Castle Esplanade and the Scottish Parliament. It is also rather weather dependent. My first impressions of the flags themselves are that they are a rather limp hiya instead of a robust hello.

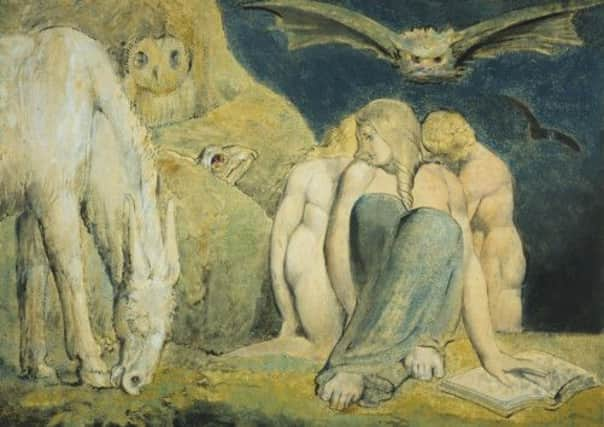

There’s no mistaking the robustness of Witches and Wicked Bodies, at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Professor Deanna Petherbridge’s timely and well-researched exploration of the representation of witches and witchcraft in art. It’s an exhibition that, if you are a woman of even the mildest feminist sensitivities, is a bit like being bludgeoned repeatedly with a severed limb. From the opening salvo, Veneziano’s 1520 Witches Rout, which features a baby-munching crone pulled along on what looks like the skeleton of a dinosaur, the show is a series of the most amazingly imaginative art works and the worst misogynist imagery.

Visually as well as intellectually, witchcraft is a series of reversals of the natural order of things. Old hags copulate with young men, their legs in a tangle that connoisseurs of erotic paintings would recognise as the wrong way round. They ride their animals back to front, get their orifices mixed up and indulge in the “arse kiss”, a shocking reversal of the papal kiss of peace. The witches’ withered and useless breasts have poisoned teats and are more like penises. Instead of suckling children they eat them. They learn to fly on broomsticks and phalluses. Artists played with these conventions knowingly and wittily – for his Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat, Albrecht Durer even reversed his own monogram to reflect the world turned upside down.

There are light spots – in a section dedicated to triumvirates from Hecate to Macbeth, Daniel Gardner portrayed Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire as a sexy witch – and real masterpieces like Salvator Rosa’s incredible Incantations. But for all the sport, this is serious stuff.

Advertisement

Hide AdEvery era since classical times had its own witches, century after century, generation after generation. Catholics sniffed heresy, Protestant reformers sniffed Catholicism, enlightenment intellectuals saw the witch as the remnant of superstitious folklore yet still revelled in new sciences and old ideas which related ugliness or malformation to evil and saw childless women as useless. The awfulness of urbanisation was represented by Blake through witches, and Victorian sexual obsessions embraced witches and sorceresses with both prurience and desire, artists generally falling for the latter.

Some of these works, particularly Goya’s Caprichos, are invested with satire, some of them took place against the backdrop of real and terrible witchhunts, of terror meted out in small communities or on big political stages.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt’s the most modest exhibits that are the most upsetting: the simple black type, with ominous red highlights, for exmample, of a Nuremberg edition of the Maleus Maleficium, the Hammer of the Witches. The printing press had barely been invented before it started churning out demonologies and guides to sniffing out and punishing witches. Of course, the weakness of women and their sexual insatiability meant they were more susceptible to the devil, that and their fiendishly clever recipes of boiled babies bones and fat to create a special salve for flying.

Well made as it is, there’s something missing in the show. Somewhere amongst the artistic and official versions, including James VI’s writings on witchcraft, you long for a little bit of historical testimony, for the real, terrible voices of the witch-hunt and the inquisition.

At Inverleith House, the transformation of a broomstick into a flying phallus would have been child’s play for the late Austrian artist Franz West, who never lost an opportunity for a puerile penis joke. West somehow represented a different Austria to the official version. The child of communist parents, an artist who in his early career worked outside the system, he understood avant-garde artists like the Viennese actionists, but seemed to find all the high drama and body fluids rather ridiculous.

West made furniture that looked like art, and art that you could sit on, sculpture that was no more than squidgy polymers. His exhibition of monumental outdoor sculpture, Meeting Points, seen in Edinburgh in 2001, was plain funny. His mother was a dentist and he specialised in a wonderfully off kilter palette that often reminds you of dental putty.

Authorship was not of great interest to West, even after his rise from an artist’s artist to great fame towards the end of the 1990s. He ran a vast studio and collaborated with young unknown artists as much as art stars like Michelangelo Pistoletto.

Inverleith House is crammed with works. It starts with a fantastic splat – a pink blob of chewed gum, smeared on glass. It happily goes even more lowbrow from there. The first room is a series of interior design works with Anselm Reyle, the younger artist’s fractured neon modernism filtered through West’s irreverence, with neon light installations crammed shoulder to shoulder with rough-hewn wood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAfter this, and a Douglas Gordon signature text work, you could spend hours in agony working out from the painful key what artwork is what or whose, or you could treat the whole lot as a single installation packed with West’s trademark disciplined mess – useless utilitarianism.

Appendages squeeze out of socks; a dining table is set off kilter by a giant green fluffy ball that hangs above it; there’s a sculpture made from Styrofoam and ping-pong balls and a beer mug filled with bottle tops. The theme of minor works made in collaboration is no substitute for a big museum survey, but it’s always fun spending time in West world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAt Summerhall, Fiona Banner’s small, disciplined solo show Vanity Press reflects her interest in words and things. Banner’s signature work The Nam, took war films and transcribed them into written texts, scene by scene. She is interested in masculine obsessions, classification and categories, in collections, descriptions and taxonomies. In Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries she once suspended a decommissioned fighter jet. Stripped of its liveries down to the metal, it was hard to know what category it had now become. At Summerhall, her film Chinook shows the heavy-lift helicopter performing balletic manoeuvres rather than troop movements or battlefield supply.

Banner is fascinated by language and its limits, and the way words become unstable when they try to encompass sex or violence. A stack of Jane’s aircraft guides teeter in a tall pile in a parody of sculpture. But words can be usefully employed when it comes to the description: in the film Mirror the actor Samantha Morton recites the verbal portrait Banner has created of her in lieu of a nude life drawing: “skin the colour of bruised peach, knees a knot of shadow”. It’s all words, a parley.