Visual art review: Sarah Lucas, Glasgow Tramway

I’ve rarely seen so many people I view as unflappable looking mildly flapped. At the opening night of Sarah Lucas’s new exhibition at Tramway in Glasgow, it was hard to know which way to look. Chatting to a friend, it was difficult not to be distracted by the enormous photograph of a naked man with a milk bottle and a pair of digestive biscuits between his legs which loomed over her right ear. Leaning over to speak to a colleague our conversation was all but obliterated by the persistent whoosh of a giant hydraulic arm that was relentlessly pleasuring itself, though it didn’t seem a pleasure, more a miserable, endless grind.

Half of Lucas’s enormous, impressive and at times dispiriting show is like this: a throbbing pink conglomeration of comedy phalluses, in resin and fibreglass, in pink rubber, even in concrete. There’s a vast wall of old photographs of the artist’s then boyfriend, the artist Gary Hume, his limp member obscured by assorted upright flowers and fruit and vegetables or a frothing can of beer. That’s only the wallpaper. As a writer you feel you need to consult your thesaurus or your big book of euphemisms. There are only so many times you can write the word penis in a newspaper article. Other art folk have suggested a new art history bible for the discerning critic – published by Viz magazine, it’s called the Profanisaurus.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe other thing that was making people flap at Tramway was the presence of the artist herself. This was nothing to do with the clichés of celebrity, but everything to do with being genuinely starstruck. The dancer and choreographer Michael Clark was in the room too; that pumping arm had been made for a production by his dance company. Students were queuing up to speak to Lucas. Confident art people came over all tongue-tied. The artist, a key figure in British art for the last two decades, has an extraordinary charisma.

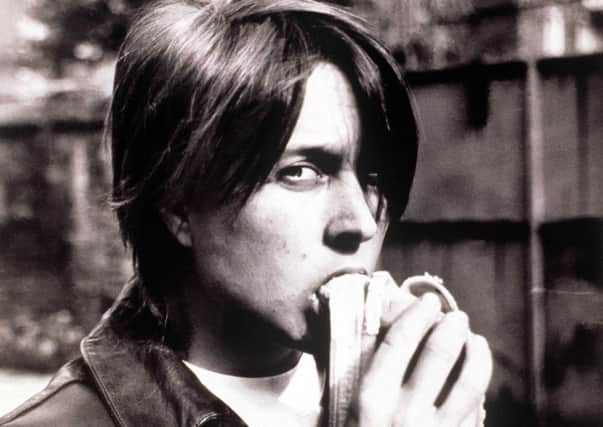

Lucas’s persona was always a key component of her art. There was her natural tomboy appearance, a kind of roughness and volatility, and an underlying shyness. Does any of this matter? With Lucas it does. More than any artist of her generation, she manages to examine that curious sensation of looking out of a body that is looked at and looked in upon. She used her natural appearance against the clichés of femininity. With her scrubbed face, lank hair and fag in mouth, she pictured herself as a male rebel – an image all the more triumphant for its effortlessness. But she also used herself against a dominant, unthinking masculinity and against the absurd way we are reduced to our bodies: a sum of our constituent parts.

At Tramway, she has parked a huge juggernaut in the gallery. Its cab is pasted with topless photos, its windows steamed up. There’s a shed entitled Chuffing Away to Oblivion similarly adorned. This is the horrible heart of a certain male culture and it doesn’t seem to reside in the chest. At the centre of these works is the curious doublethink that girls of our generation grew up with, the smutty humour, the knob gags, the tits and the growing grim realisation beneath the grin that people saw you that way, that the friendly bus driver was reading the Daily Sport and looking at your chest.

In Lucas’s sinister shed, walls are covered in varnished pages from the Sun, the Mirror and the Sport. There are breasts everywhere and the stale smell of smoke. The most frightening one to me seemed the archly phrased advert from supermarket Safeway for a piece of fruit. Lucas reminds us we live in a world where even a melon is lascivious. Lucas laughs at it all – look at those giant concrete marrows over there! – but there’s a rage beneath the laughter.

She also revels in the absurdity of the human condition, the relentless rhythm of life beaten out beneath the covers, but by outdoing the lads at their own game she rises above the everyday. There’s a cool distance, a knowing. There has been a recent fashion to understand a whole century of art as one giant sequence of male penis jokes, from Duchamp’s notorious Fountain onwards. Lucas, who grew up on a Holloway council estate the daughter of a milkman, had the temerity to casually, almost accidentally, insert herself into that history. And she found she had a place. And in recent years, in a renewed burst of serious attention, sparked by a fantastic sequence of sculptures entitled Nuds, we found that she deserved it.

North London lives on in the second half of the exhibition. A smashed up Volvo lies with its windscreen panned in, the broken glass giving it it’s title, Islington Diamonds. A vast wall of black and white photographs of empty car parks reaches to the ceiling. These are like Warhol’s use of the tabloid photographer WeeGee’s crime scenes. Except the crime hasn’t happened yet. Or maybe, in a show that is grim and industrial and plays to the heights and depths of Tramway’s space and history, the crime is all around us and it is happening all the time.

Advertisement

Hide AdNow that she lives in rural Suffolk, Lucas’s art has not been tamed. Two recent giant concrete penises are set on plinths made of crushed motor car. Their texture is informed by the bleached wood and flint of her rural surroundings. They are beached and beautiful. You think of a whole tradition of British sculpture: of Paul Nash or Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth. And then you remind yourself that for heaven’s sake it’s just a giant willy that you are staring at. Is this foolishness the driving force of art and life? Is that pulsating feeling not just an urban rhythm after all?

Gritty, grimy, grinding, spectacularly silly, Lucas makes you feel grubby. Her neon coffin reminds you you’re alive, but only just. As the label says, this isn’ta show for unaccompanied children. Despite its adult content, Lucas’s art retains that child-like handling of materials and brilliant improvisation, but that’s not childishness. As this show proves, it’s just a kind of natural authority.

Rating: * * * *

Until 16 March