'My Normality' project invites artists to reflect on a year that's been anything but

Earlier this year the Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival (SMHAF) advertised a new commission, My Normality. The idea was to invite artists across Scotland to express what "normality” means to them, following a year that has been anything but normal, all across the world. Almost 100 applied, and the proposals – like the lockdown itself – challenge a lot of ideas about normality.

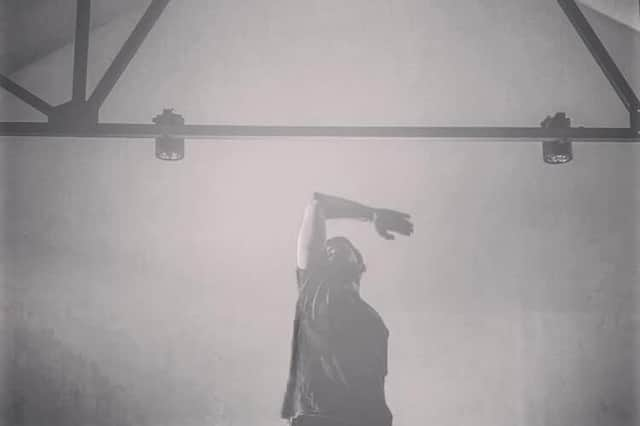

Announced this week, the eight selected artists include Jack Webb, a choreographer who will make a new dance film encouraging viewers “to resist the pull of speed, fear, and productivity” as lockdown finally lifts. As Webb explained in his proposal: “Being still, being quiet, stopping, distance and home have always been my normality pre Covid-19.” Other artists will make very personal work about the normality of experiencing casual, everyday racism and the mental health impact of living with endometriosis, anorexia or cystic fibrosis. Dundee-based spoken word performer Eilidh Morris captured the spirit of many of the proposals, when describing the film they will make with musician Johnny Threshold. As Morris put it: “I have attempted again and again to fit into the worlds that seems normal for those around me, only to find myself falling behind, overwhelmed by the ways that none of this has ever felt natural, or normal, to me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdIn other words, everybody’s normality is different, and this was always going to determine how Covid-19 impacted on people’s mental health. Since last year the media has been full of phrases like “the new normal” and “going back to normal.” The suggestion, often, is that the “new normal” has been something to endure while going “back to normal” is something to look forward to. While this will be true for a lot of people, the picture is complicated. Research by the Mental Health Foundation indicates that those with long-term physical or mental health problems have been more likely to feel distressed during lockdown compared with UK adults generally. However, a significant number of My Normality applicants talked of feeling anxious not about lockdown itself, but about the end of it, about mainstream society, a quieter and perhaps more reflective and self-aware place over the past year, returning to a frenetic “normality” that rarely feels welcoming or inclusive to them.

Each year the theme for SMHAF is voted on by the festival’s numerous regional co-ordinators across Scotland. There are often lively arguments; it’s not easy to choose a theme that will comfortably bind together almost 300 events all over the country, mostly programmed independently by artists, community groups, and mental health activists. But this year’s choice – “Normality?” – was almost unanimous. It raises lots of questions, after all. How can the way so many people lived before lockdown be considered “normal” when it was doing so much damage to our mental health? If/when life does go “back to normal,” who will remain excluded from that? And what should we be learning from a year that has turned the world upside down, forcing us to re-evaluate what we think of as “normal” life and “normal” behaviour?

To an extent, SMHAF has been asking questions about normality since it began 15 years ago; part of the festival’s mission is to highlight the normality of mental ill-health, and to reduce the stigma around it. Much of this year’s normality-themed film programme was shot before lockdown began, although it now has an extra layer of resonance. Neighbors, for example, is a feature length documentary about a group of people who have spent decades confined to a Croatian psychiatric institution and have to readjust to “normal” society when the building closes its doors. The festival is also screening two series of short films from all over the world, exploring how people’s daily lives and mental health are influenced by factors including neurodiversity, body image, sexuality, trauma and long-term health conditions.

I’m particularly looking forward to hosting a Q&A with film-maker Johanna Faust, who began making her documentary I’ll Be Your Mirror in response to a difficult life dilemma – should she say yes to a big work opportunity abroad that would mean being away from her children for a year? It’s the kind of choice that prompts much more judgement if it is a woman making it rather than a man. For Faust, though, it also prompted memories of decisions made by her mother and her grandmother and how they impacted on her as a child. In the film, Faust talks of an anger her mother felt towards motherhood that “lives on inside of me.” Several layers of “normality” are being explored here – the social expectation that mothers, more than fathers, should put family life before work, but also our expectations of how parents feel about children and how children feel about their parents.

While the lockdown continues to make what was once a “normal” SMHAF impossible, this year’s festival is significantly bigger than last May’s first online programme, now its many creators have had more time to adjust to new ways of doing things. With over 150 events this May – mostly online, but some outdoors, reflecting this year’s Mental Health Awareness Week theme of “nature” – there is a lot going on. The film programme, launching with a Zoom gathering for the International Film Awards on 3 May, will be showcased online via Indy On Demand, with all titles available on a Pay What You Can basis or through a festival pass. All screenings will include a live, open discussion with filmmakers and guests, and there are also opportunities to get involved through a series of participatory workshops. The festival will close on 23 May with its Writing Awards, in partnership with Bipolar Scotland, which had over 300 entries this year. In between there is a huge range of events organised by people all over the country, including exhibitions, workshops, storytelling performances and an open mic night. Whatever your normality, hopefully there is something that piques your interest.

Andrew Eaton-Lewis is arts programme officer for the Mental Health Foundation. The Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival takes place online and outdoors from 3-23 May. Full listings at www.mhfestival.com

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions