Is depression '˜endemic' among stand-up comedians?

AS A comedy journalist, I’ve asked plenty of inane questions. Until now though, no comedian has ever been bold enough to confess they felt suicidal as we spoke. Certainly, I’ve talked with a few about trying to kill themselves. But only after they’ve recalled their failed, often slapstick attempts on stage.

Most people are aware of the depression of performers like Spike Milligan and Tony Hancock and the “tears of a clown” cliché – the idea that comedic genius is inextricably linked to mental illness.

Advertisement

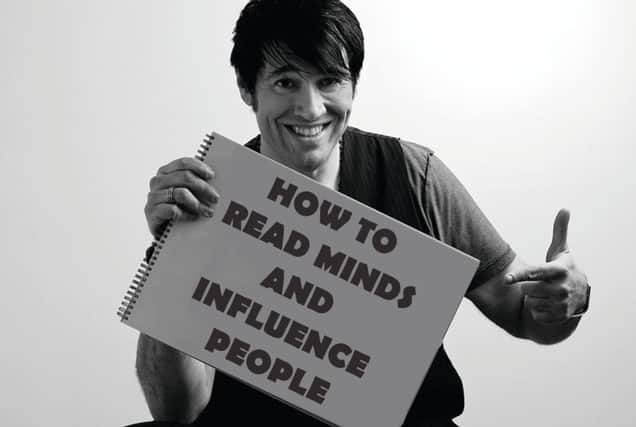

Hide AdComedian and mind-reader Doug Segal is “absolutely convinced” of a connection, noting that “there are a number of hidden Facebook groups for performers with depression”, estimating that one in five acts on the stand-up circuit belong to them. “That feels about right, possibly higher,” he says. “It’s endemic. There’s an awful lot of my mates in there.”

Segal suffers from cyclothymia coupled with recurrent depressive syndrome, a form of bipolar disorder. That’s the same condition Stephen Fry has, characterised by mood swings from emotional highs to deep depressions. “As I speak to you now, I’m genuinely feeling suicidal,” he says. “I’ve been around this rodeo so long that I don’t think I’m in any danger. But I had a dream last night that I’d arranged my suicide in a Dignitas-style way and told my mum it was going to happen. Then the date got put back and I was panicking that I’d upset her for nothing.”

Segal has manic creative bursts but “also finds some of the best, most solid writing work I do is when I’m in a low”. He adds: “These are the things going through my head right now and I think there are a lot of performers with bipolar or depressive disorders. Maybe it’s something that drives us to the stage. It could well be the endorphins.”

Segal, a psychology graduate with a background in advertising, is aware of the apparent irony in sharing these thoughts while promoting his new show, I Can Make You Feel Good, in which he explores what makes people happy and pledges to make the audience feel euphoric. Like most comics, he spends a lot of time in his own head, not least post-gig, when the adulation and applause is swiftly replaced by a lonely hotel room. Performing can be cathartic and allows him to “shine a light on the darkness. But in another way, it can also make the shadows darker too,” he says.

Richard Herring says “there’s a sort of drug element” to stand-up. Moreover, when he’s on stage, “it’s the only place I feel I can lose myself,” he says. Equally though, part of the appeal of being a comedian is that even the worst moments in his life can be channelled into material. “There’s a sort of positivity in the negativity,” Herring says. “I occasionally fantasise about losing a leg or something and imagining what a brilliant show I could do about that.” He says audiences are “turned off” by a comedian coming on and saying “my life’s brilliant and I’m amazing”. Which may explain some of the appeal of acts like Jerry Sadowitz, Ian Cognito and Lewis Schaffer, who project cynicism, bitterness and a sense of marginalisation.

Herring’s lack of recent TV exposure is a bittersweet running gag. He jokes that his fans want to keep him to themselves, “that they want me to carry on being unhappy so my comedy remains what they want it to be”. Similarly, I once asked Jon Richardson whether he was, on some level, wrecking his relationships to sustain his misanthropic stage persona? He’d moved to Swindon to escape his friends and focus on his stand-up. Last year though, he married fellow comic Lucy Beaumont. And it doesn’t appears to have done either’s career much harm.

Advertisement

Hide AdHerring suggests that there’s a danger in “starting to believe in the character you’ve created or taking yourself too seriously”, and that actually, achieving your goals might be the greatest obstacle to becoming a great comedian. “A lot are driven by feeling that they’re a failure or railing against something,” he says. “Suddenly, if you become very successful, it gets quite hard to rail against anything. So you have to create this pretence that you’re not. And it starts to eat away at itself then.”

He’s tackling this conundrum with his new show Happy Now? He rejects the notion that contented comedians lose their edge. Married and with a baby, he’s twisting the bounty of domestic bliss into exploring “happiness as torture in itself”. Herring says: “The terrifying thing about having a wife and family is that you can lose them in a variety of ways. Being happy is more tortuous than being unhappy, because at least then you know there’s a way out of it and a way up.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAt 48, Herring remains “playful and skittish, a perpetual child within an adult’s body that is getting battered by time”. Being overlooked by TV commissioners keeps driving him towards experimentation and a fragile balance of eccentricity, creativity and self-indulgence. He hosts a podcast in which he commentates while playing himself at snooker, “a protracted joke … almost performance art… debating, almost literally, mental illness and where your sanity rests. That’s both for me and anyone listening to anything so deliberately tedious.”

It was on Herring’s other, more conventional interview podcast that Fry revealed his suicide attempt, with the comic Ray Peacock recently reflecting on his there too, before confirming his hiatus from stand-up. Comedy offers a much-needed outlet for discussion of mental health issues, but may just exacerbate symptoms for some.

So should you be suspicious of a stand-up who calls his show How To Be Happy and closes it with a six-minute prescription for contentment? Kai Humphries is hailed by his peers for being much the same on stage and off. And he’s engagingly honest.

“I don’t feel like a specialist in anything” the Edinburgh-based Geordie says. “I don’t have much education. But I am a happy person so I wanted to look at my life, see what the ingredients are and share them with other people.”

He’s not entirely alone on the stand-up circuit in being avowedly happy. “But the difference is, some comedians, even close friends of mine that I love and adore, they’ve got this hole that never seems to be filled,” he says. “Like they’re chasing a carrot, they’re looking for success at something.”

After working in a leisure centre as both a lifeguard and toilet cleaner, alongside factory and cleaning work, he feels that he “ate the carrot a long time ago, when I quit my job and started doing comedy for a living”. Gigging abroad, supporting his friend Daniel Sloss on tour, “it’s all a bonus, they’re not things I need to fill a hole”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAt the same time, he’s found fulfilment in running Punchdrunk comedy nights with his brother Gav in his deprived home town of Blyth, Northumberland, with food-bank drives and charity events such as a recent comedians’ boxing match in aid of a Newcastle toddler’s cancer treatment in the US.

“Even though we’ve not been on TV, we’ve got this local notoriety,” Humphries says. “It’s been brilliant, the community spirit has been really united since we started running these events. I’d still like to get on TV, but more for my people at Punchdrunk, to show them a local boy doing it on a national stage. I’d like to give that to them.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad• Doug Segal: I Can Make You Feel Good, Tron Theatre, Glasgow, Friday, 9.30pm; Richard Herring: Happy Now?, Citizens Theatre, Glasgow, 17 March, 8pm; Kai Humphries: How To Be Happy, The Stand Comedy Club, Glasgow; Friday, 5.40pm. www.glasgowcomedyfestival.com/