Arts review of 2021: Joyce McMillan on the year in theatre

If 2020 was the strangest year in the whole history of Scottish theatre – the promising start, the sudden silence, the rush to find new ways of making work online – then 2021 has been its unique and unsettling child, a year of two halves in which the early months were still almost bereft of live performance, while the summer and autumn gradually built towards a thrilling explosion of long-suppressed theatrical energy, but one that still leaves unanswered many of the haunting questions raised during those 16 months of darkness.

In early spring, for example – and at the top end of the scale, in terms of resources – the Lyceum and Pitlochry Festival Theatre launched their year-long Sound Stage series of monthly audio productions, created in collaboration with independent radio company Naked Productions, and featuring playwrights ranging from Mark Ravenhill to Gary McNair and John Byrne; at the other end of the scale, meanwhile, young playwright Kenny Boyle took matters entirely into his own hands by recording a series of brilliant and chilling online lockdown stories under the title An Isolated Incident, featuring haunting footage of Scottish landscapes from the Borders to his native Lewis. Dundee Rep Studios – the theatre’s new online strand – released a superb onstage filmed version of their 2020 show Smile, about football manager Jim McLean; and interesting mixtures of filmed performance and theatrical space also featured, for example, in Helen Milne Productions’ Distance Remaining (a trilogy of terrific solo performances from Dolina Maclennan, Karen Dunbar and Reuben Joseph), in the Citizens’ film version of their terrific two-hander The Macbeths, and in Ayr Gaiety’s fine tribute to amateur drama, Meet Jan Black, starring the inimitable Maureen Beattie.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn the spring, organisations like the Edinburgh International Children’s Festival began to talk not just about online work, but about “online and outdoors”; and theatre in Scotland began to move into an intense outdoor phase. The pioneer was Grid Iron artistic director Ben Harrison, who as early as February launched a project called Chalk Walk, involving a single audience member walking around part of a largely deserted Edinburgh shooting the breeze with actor Neil John Gibson; and Chalk Walk contributed to the development of another superb promenade show later in the year, in Gibson’s first-ever play With You In The Distance, about a gay love affair in 19th century Glasgow, performed to lone audience members during a walk through Glasgow Green.

In June, Pitlochry Festival Theatre launched a hugely successful outdoor summer season, centred on a gorgeous amphitheatre built into the wooded hillside behind the theatre, and opening with an exquisite production of David Greig’s Adventures With The Painted People. The 2021 Edinburgh Festival and Fringe often continued the outdoor theme; notable August hits included Julia Taudevin’s Move at Silverknowes Beach, women’s football show Sweet FA at Tynecastle Stadium, and Grid Iron’s Doppler, a superb Fringe show about the crisis in humanity’s relationship with nature, staged in beautiful woodland at Newhailes House. At Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens, meanwhile, there was a brilliant Winter’s Tale from the Bard In The Botanics company.

Back in the theatres, there was a sudden rush of memorable work, ranging from Michael John O’Neill’s powerful monologue This Is Paradise at the Traverse, to the live staging at the Lyceum of Hannah Lavery’s Lament For Sheku Bayoh, the ground-breaking National Theatre of Scotland and EIF show entirely created by a company of black Scottish woman. Both The Lament For Sheku Bayoh and Move featured Beldina Odenyo Onassis, the hugely gifted composer and singer known as Heir Of The Cursed, who sadly died this autumn, aged only 31. Scottish theatre mourned her; and also Michael Emans, artistic director of the touring Rapture Theatre, who died in the summer at the age of 50.

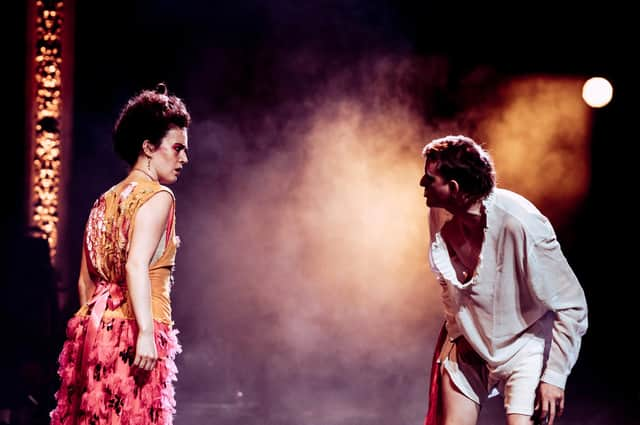

Then, via Angus Farquhar’s remarkable Over Lunan event at Lunan Bay in September, the year entered an astonishingly rich autumn season, dominated by two outstanding large-scale shows in the National Theatre Of Scotland’s The Enemy, a thrilling updated version of Ibsen’s An Enemy Of The People by Kieran Hurley, and by the Lyceum’s return to live theatre with a fabulous, profoundly theatrical production of Jo Clifford’s version of the great Spanish Golden Age drama, Life Is A Dream. Jemima Levick took the helm at A Play, A Pie And A Pint in Glasgow, opening with a sparkling 12-show season. Perth Theatre presented a spiky new take on Moliere’s Don Juan by actor-turned-writer Grant O’Rourke, the Tron offered an all-female Tempest as well as the Citizens’ fascinating double bill of Becket’s Krapp’s Last Tape and Linda McLean’s Go On; and Edinburgh’s acclaimed Lung Ha company – working with Plutot La Vie – produced one of their finest shows yet, in their surreal October farce-cum-thriller An Unexpected Hiccup.

Amid this long-awaited rush of activity, though, all the troubling questions raised during lockdown continue to demand attention; questions about the profound inequalities within theatre highlighted by the pandemic, and, beyond that, about the new audiences for theatre that emerged during lockdown – people who long to be in touch with the work of their local or national theatre companies, but who often simply cannot make it to live theatre, for reasons of health, finance, or caring responsibilities.

For that audience, the sudden switch to online work during the pandemic offered a rare opportunity to feel part of a community from which they will now, once again, risk being excluded. And unless theatre can begin to find new ways of reaching out to that wider community, and beyond its traditional power structures, then there is a sense that for all its huge creative energy, its future will be precarious; not least in terms of the funding that governments have continued to provide during this crisis, but which may come under threat if theatres rest for too long on their well-earned artistic laurels, and on the simple relief of knowing that – one way or another – they have succeeded in surviving the pandemic years, so far.

A message from the Editor

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions