The write stuff: A Christmas story by Laura Marney

He had found her in the chair.

Eighteen years ago, while Roddy’s teeth were still slightly too big for his nine-year-old face, he’d won the regional heat of a Hoseasons talent contest by singing She’s the One. What had particularly impressed the judges was how he’d sang to the ladies keeping the last line pointedly for his mum.

The prize was complimentary accommodation in a super deluxe six berther for the weekend of the final. Mum, or Betty as she preferred, loved it.

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘Sea view: swanky, eh?’ she said, throwing herself onto one bouncy sofa while Roddy threw himself on the other, ‘We could get used to this.’

After that they travelled the country entering talent contests. He didn’t always win, sometimes he didn’t even get placed. Sometimes the caravans smelled of damp but Betty was always upbeat.

‘A true star always shines, Roddy,’ she was fond of saying, ‘no matter how difficult the circumstances.’

As the silverware stacked up on the mantelpiece the cash prizes were reinvested in voice and piano lessons. Betty worked late Tuesdays and Thursdays, always starving when she got home, but the extra money paid for a top of the range keyboard from the catalogue.

Right from the start she’d encouraged him to start the band. She let them rehearse in the living room while she stayed in the kitchen making tea and toast. He told them they had to be 110 per cent committed and Betty agreed.

When Mr Munro came up to complain about the noise Betty firstly apologised but she ended up arguing, calling him ‘a philistine’ who ‘didn’t know a good melody from a bottle of Buckie.’

Advertisement

Hide AdThey moved to a rehearsal studio but they kept the name Betty’s Kitchen despite the bass player’s grumbles. Betty chipped in for the deposit and stood guarantor when they bought the P.A, her way of subsidising the arts, she said.

He’d phoned the doctor immediately. He found her slumped in the chair in front of the telly, her head at a funny angle. When he finally got through he told him it was bad this time.

‘How bad?’ The doctor asked.

“One side of her face is blue and she’s not breathing.”

The doctor asked how long she’d been like that.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I told you, I’ve been waiting five minutes and she’s still not breathing.”

‘Oh,’ the doctor agreed, ‘that is bad.’

There was hardly anybody at the funeral. Except for the band, in borrowed suits, there was only three women, Betty’s pals from the back-shift. The women hadn’t dressed up and they huddled together at the back.

There weren’t relatives to act as pallbearers so after the mass, while the undertakers took the coffin out, Roddy’s band played. He worried the priest would disapprove but the priest didn’t care either way. Roddy had draped the white silk scarf over her coffin and laid on top one red gerbera, her favourite.

He had written the song for her: An Elegy for Betty. He knew it was his best so far; when they got a record deal it would be their first single. This performance, his most important gig ever, had to be perfect. His mind ran ahead to a line in the next verse,

‘One day he will lay me down

And I look up to him.’

He’d nicked it from her secret stash of poems.

Roddy worried that when he sang it his voice would crack but his professionalism did not desert him. He sang as he had been trained to, locked into performance: his fingers moving on the keyboard, the sound from his chest, the breath from his mouth.

The women sniffled into their hankies, nodded and mouthed, ‘lovely,’ as they filed out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs they were packing up the P.A. Roddy had the feeling of having swallowed something bad. It gave him a weird stuffed-up empty feeling.

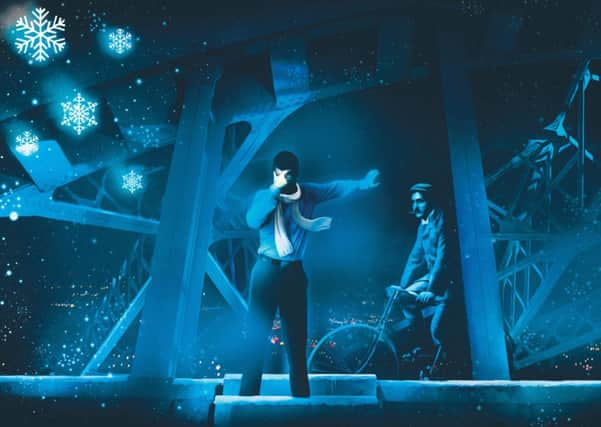

From his squatting position on the high ledge Roddy still had the stuffed-up emptiness. It had never left him. The fierce wind was turning the snow from soft powder into spiky crystals, even the scarf felt cold against him, the white silk scarf he’d never worn again till now.

Advertisement

Hide AdBack in the seventies, when Betty was a young thing, the guitarist from Showwaddywaddy threw his scarf into the crowd and she’d caught it. Once she’d wrapped it round Roddy’s neck as he walked on stage. He won first prize that night.

‘Your talent that won that contest, not an old scarf,’ said Betty.

But he wore it every time after that.

He was glad of it now, people driving on the road below would see the quivering white against the night sky. They’d think it was a falling star, a supernova.

Roddy had anticipated problems with the police. He might be spotted and reported but the bridge was quieter now; the evening traffic had tailed off to the occasional squish of a passing car. There were people walking on the other side of the road when he’d lowered himself down from the railings, people hurrying home to start their Christmas celebrations, they must have seen him. Their lack of response shocked him. He stood up and grabbed the railings, pulling himself up to look along bridge. There were no pedestrians, only a few cars and an old guy coming towards him on a racing bike. He could see the old bloke’s balaclava under his cycling helmet as his thin wheels scooshed through the slush. Tightly curled round his bike, the man cycled past.

‘Merry Christmas you bunch of bastards!’ Roddy shouted into the wind.

Something about this situation, the snow and the bridge, felt familiar: that movie that had been on telly last night for the umpteenth time, the soppy movie about James Stewart going around being nice to everyone; a great guy who doesn’t realise it so he’s about to top himself until his guardian angel shows up.

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘Aw Clarence,’ James Stewart moans in the film, ‘this whole town would be better off if I had never lived!’

Betty would have been better off if Roddy had never lived.

Life as a single parent had not been easy for her. Without the baby she might have got married, had a career, she was clever enough, maybe even published her poems.

‘Parky tonight, isn’t it?

Advertisement

Hide AdRoddy heard a muffled shout and looked up. It was the cyclist, speaking to him through knitted wool. The old guy hadn’t even taken off his helmet or balaclava. Roddy turned his back on him.

’Are you all right down there, son?’

‘I’m not your son. And don’t tell me your name’s Clarence.’

The cyclist said nothing, prompting Roddy to ask, ‘well, what is it then?’

‘Eric.’

‘Cynical Hollywood manipulation; holiday feel-good shite to get people to buy into Christmas,’ Roddy told Eric, ‘The whole town actually would be better off if I’d never lived. Who else d’you know who’s killed their own mother?’

‘Nobody,’ Eric confirmed.

‘Let me tell you a feel bad story.’

And Roddy told Eric about the blood clot that had formed when Betty was seven months pregnant and stayed in her leg until the day he’d found her in the chair.

‘That’s not murder,’ Eric scoffed.

‘Did I say murder? I said killed!’

Then he told Eric how he’d also killed their next-door neighbour: how Marion had cancer but came to their door in her nightie asking him to go to the offie for a half bottle. How vehemently he’d refused but how Marion said that if he didn’t, she’d go to the shops herself. How he finally relented.

‘The next morning she was dead.’

Eric nodded, ‘You brought her a wee bit comfort in her last hours.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘OK, I’ll give you another example: that time my Uncle Martin had a stroke. Betty said it was Uncle Martin’s own idea to give us his old wardrobe and his decision to bring it upstairs. She said he should have waited for me to help him like we’d arranged. Betty said: so what, if I was late? He shouldn’t have been so pigheaded. But obviously if I’d been home on time it wouldn’t have happened, would it?’

Roddy looked up but Eric only shrugged, his breath seeping out of his balaclava, a ghastly ghostly spectre.

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘He’s in a wheelchair now. One side of his face droops, like that. He can’t speak but he still looks at you in that twisted, crippled, accusing way, I can’t bear it.’

‘Are all these stories just about you?’

‘No,’ said Roddy, defensively, ‘and I’ll prove it. ‘

He told him about the record deal. That proved they were better off without him.

Eric didn’t argue.

After the funeral he’d missed rehearsals and they’d thrown him out of his own band.

‘Eight years I put into that band. Eight years, man.’

He thought they’d fall apart within weeks but they didn’t. They changed the set, dumping Roddy’s plangent ballads for the crap pop the bass player was knocking out. Two months later they had a recording contract. They weren’t even called Betty’s Kitchen any more. Earlier that day Roddy had seen them interviewed on MTV. The interviewer asked how they’d got the band together but nobody even mentioned Roddy. The bass player was now fronting the band and their first single All the Christmas Honeys was climbing the charts. The voice and piano lessons, all the overtime Betty worked to pay for them, all for nothing.

‘A true star always shines.’ Roddy sneered, ‘You should hear it; it’s music for wee girls.’

‘Aye,’ Eric laughed, ‘I’ve heard it on the radio. All the Christmas Honeys, it’s a good wee toe-tapper.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘Right, that’s it. Piss off. I mean it!’ Roddy screamed, ‘You’re really annoying me now. Go on, piss off back to your…’

‘Fair doos,’ said Eric, pulling his bike off the railings and hopping on, ‘Merry Christmas son.’

Eric whistled as he cycled into the distance.

Advertisement

Hide AdRoddy felt rage warm his body like egg nog. He stood up, stuck his head through the railings.

‘Come back! Get back here, I want you to see!’

Roddy watched the old man’s backside bob as he cycled away.

‘OK then. Stick your glib yuletide platitudes up your arse! It’s not a wonderful life. You’re too delusional to see it. You’re pathetic!’

But Eric continued pushing the pedals, his frozen breath a halo around his head.

‘I’m coming for you, old man. I’m going to hunt you down,’ Roddy screamed, hauling himself over the railings, ‘I’m going to find you and I’m going to f***ing kill you!’

As Eric disappeared into the freezing fog Roddy could still faintly hear him whistle All the Christmas Honeys, the sound distorting from this distance.

Roddy fell heavily on the pavement and struggled to get his breath, the icy air rasping in his throat, damaging his vocal chords. He lifted his head but Eric had disappeared and, too knackered, Roddy rolled on to his back and looked at the stars. There were loads of them, so many he couldn’t see them all at once. He found one and then spent ages trying to find it again, the moon floating right across the sky. Despite the cold he was enjoying the lovely sleepiness he felt steal over him. Ah, there she was, twinkling away there. He’d lost her but now that he’d found her again, he wouldn’t take his eye off her this time. He held up a corner of his white silk scarf and waved at the star, the twinkliest star, the one that twinkled brighter than all the others.

Advertisement

Hide Ad• Laura Marney is the author of four novels: No Wonder I Take a Drink, Nobody Loves a Ginger Baby, Only Strange People go to Church and My Best Friend has Issues. May 2014 will see the release of her latest novel, For Faughie’s Sake. She writes stories and plays for radio and is a part-time lecturer at Glasgow University on the Creative Writing Programme.